FICTION | ISSUE SIX

Butter

♦

By AFABWAJE KURIAN | Fall 2015

Little Girl in a Park Near Union Station, Washington, D.C. [ca. 1943] | FSA - OWI Collection

Ms. Edwards’s heels clicked on the classroom floor, steady and rhythmic, moving Yeye into the lyrical waves of her voice. It was fifteen minutes before recess, and Ms. Edwards was reading aloud from Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, the final book selection of the year. The promise of summer crept in through the open windows, not seeming to harm the sugar maple trees and daffodils outside, but it hunched the students’ shoulders, relaxed their fingers so they held their books at angles, and weakened their legs so they ambled through the hallways. The school year ended soon, and in a few days, classroom sessions of book report presentations and fraction games would be exchanged for ice cream sundae parties and movie showings.

During reading time the prior week, Ms. Edwards got to the part of the book where Cassie took revenge on her bully, Lillian Jean, by luring her into the woods. In that chapter, Cassie twisted Lillian Jean’s hair, pinned her down into the brush, and forced her to apologize for her meanness. Yeye had listened with such intensity she failed to notice her best friend Abena kicking the legs of her chair to get her attention.

“Why do you believe Cassie was upset with Lillian Jean?” Ms. Edwards had asked that day during the class discussion afterwards.

Harriet Johnson, who had been sitting in the front row, raised her purple-watch-clad arm. “She couldn’t stand up for herself,” Harriet said, smooth and sweet, so Yeye could not believe her ears. “I’d be upset too if that happened to me.”

“Good answer, Harriet,” Ms. Edwards said. “Anyone else?”

The rest of the class had been silent, and Yeye had fumed inwardly thinking that her teasing occurred on a regular basis, most of it masterminded by Yamhead Harriet Johnson. Yamhead was Yeye and Abena’s nickname for Harriet. They named her after a purple yam that grew in parts of West Africa, a tribute to Harriet’s endless accumulation of purple clothing. Abena and Yeye took immense pleasure in their code name, mouthing it to each other if Harriet walked by and convulsing in laughter. Their breath-stopping giggles a salve for Harriet and her friends’ persistent taunts.

Today, as Ms. Edwards read from a new chapter, Yeye pictured doing the same thing to Harriet that Cassie had done to Lillian Jean. Tricking Harriet by feigning servitude, learning all of her secrets, then threatening to expose her to Harper Elementary until she apologized for her hurtful words. To Harriet and some of the black kids at Harper Elementary, Yeye was the African girl with a strange accent who overemphasized her t’s when she said water or skipped her h’s when she said three. She hunted cheetahs with spears, never bathed, and trotted through her village with a pet chimpanzee. At least these were the lies that Harriet and her friends spread about Yeye. They said the same things too about Abena. Smelly jungle monkeys, they chanted on the bus, go back to Africa. They rarely called Yeye by her name: Yo-yo, they’d call her. Yin yang, they’d sing. Ya Man, they’d say and fall out in laughter.

The classroom had become Yeye’s solace, a place to escape the teasing. It was spacious and well organized, with colorful posters tacked to the walls, wooden chairs and desks arranged in four rows of five, and the teacher in command and intolerant of insolence. An oasis compared to the commotion that ensued in the school cafeteria or on the bus. It was also a welcome sanctuary from the chaos that defined Aunty Lola’s house. Last June, Yeye’s family moved from Nigeria to Delaware into Aunty Lola’s basement for a temporary stay. Aunty Lola’s surly teenage boys stomped around the house, played video games at odd hours, and slammed doors at will. Old mattresses, scores of dog-eared books, and unused or broken kitchen appliances filled the basement. And in the middle of it all, Yeye’s family tried to carve out a space to live. Though Yeye loved the warmth and freedom summer offered, she knew it brought longer days spent in the house babysitting her four-year old brother Joseph while her mother cleaned houses and her father, a security guard, worked a string of irregular shifts or attended his business classes.

“There’s smoke coming from my forest yonder!” The startling escalation of Ms. Edwards’s reading stirred a couple of the students awake. Without taking her eyes off the book, Ms. Edwards paced the front of the room, her manicured fingers turning the page and miming to life puffy white cotton fields and rust-red Mississippi earth.

Yeye looked around the classroom. With only a few minutes left until recess, the students’ restlessness had emerged. Abena’s chin rested on the sloping desk, Yeye’s former friend Debbie Taylor doodled rosebuds, and twiggy Jeffrey Larsen’s eyes fluttered half-closed. Yeye knew that Jeffrey’s cherubic face and thin pink lips belied his true nature. Yeye once caught Jeffrey cheating on a test in social studies class, peering at another student’s paper, and coloring in his multiple-choice answers. No one else saw this. Not even the strict and vigilant Mrs. Royce. Jeffrey was a slender child with a perpetually dripping nose, the kind of kid that not even a squirrel would scurry out of its way for, a child whose mother probably crushed Flintstone vitamins into vanilla-flavored yogurt and brushed his blonde hair into an unappealing bowl cut. It made Yeye cringe that Jeffrey could perform such a transgression, yet appear angelic with his baby blue polo shirts and suede oxford shoes.

Unlike some of the other students, Christopher Jenkins sat alert, seemingly enthralled by the undulation of Ms. Edwards’s voice. Christopher and Harriet were rumored to be going out with each other. Yeye used to have a crush on Christopher because he smiled at her on the first day of school. But this changed when Yeye walked past him in the cafeteria one day, balancing her meal of pizza lasagna and chocolate milk. Christopher had looked at her with his penetrating brown eyes and said to one of his friends, loud enough for Yeye to hear, “She’s ugly.”

Abena had consoled her in the peach-colored bathroom with the buzzing fluorescent lights. “You’re not ugly,” Abena said, tissue wadded in her hand. “Maybe he wasn’t talking about you.”

Yeye sniffed. “He looked right at me.”

“He’s the ugly one,” Abena said. She had giggled. “We’re the African queens.”

They could not have been African queens. Whenever Abena chuckled before speaking, it meant that she did not believe the words she was about to say. And Christopher Jenkins could not be ugly. He was a brown-skinned boy with curly black hair, and every girl in the fifth grade had a crush on him. Ugliness did not beget crushes. The whole incident had supported Yeye’s theory that boys like Christopher were not into girls like her and Abena: girls with accents, girls from places he knew nothing about, girls that were easy targets for mocking. Though Yeye had worn her best outfit that day—faded blue jeans and a sweater she picked out for herself from the thrift store, one with a glittering cartoon rabbit affixed to the front of it—it did not matter. It served her right to be called ugly. Had her father not warned her to stay away from them?

Yeye thought it unfair that Harriet had the admiration of Christopher Jenkins. Even in the classroom, where Yeye excelled, she felt Harriet’s encroachment. Like with the Harper Elementary School spelling bee competition. Yeye had landed in second place while Harriet Johnson won the first prize, spelling acknowledgement when Yeye bungled the word, forgetting the “c”. Dressed in a flouncy purple blouse and a pleated white and purple skirt, Harriet’s hands had been at her side in attention. Yeye sat near the mustard paisley curtains, listening to Harriet enunciate each letter into the microphone, feeling that the applause echoing in the auditorium should have been hers. Not Harriet’s. Definitely not Yamhead Harriet Johnson’s. Her father’s words reinforced her feelings that the spelling bee must have been a fluke and not a forecast of how their lives would be shaped. Yeye never mentioned the spelling bee to her father because it might upset him that she lost, and he would realize he was incorrect in his declarations about them.

Months ago on a cool September day, her father caught Yeye emerging from Debbie Taylor’s house on his return home from work. That was when he warned her against playing with them. As he polished his work boots, each movement of his arm deflecting the light on his gold square badge, he had explained, “Yeye, our people are smart and hardworking. We Africans come to this country and we better ourselves. Them, they were born in this country and what do they have to show for it? Don’t let the color of our skin fool you into thinking we’re the same as akatas. We’re not at all the same as them.”

When he said those words, Yeye had known her father’s dislike of them had something to do with a day he took the family to his workplace. It was a building constructed with slats of glinting turquoise glass and from a distance it floated above a grove of conifer trees. Her father had shown them where he walked on his rounds, the tiny globe cameras on the elevators, and the grainy screens he monitored. When he took the family to see the break room where he warmed and ate his pepper soup, three other security guards had sat inside the break room absorbed in a card game and appeared uninterested in their presence when they entered. The three men took turns dealing and drawing cards from the center of a table littered with empty, crushed soda cans. They resembled her father: the glow of their sky blue collared shirts reflecting on sable faces, their black eyebrows thick and unruly, and their fingers calloused and strong. Yeye’s father did not speak to them. They, in turn, did not speak to him. Her father spent little time showing the family around, only making a sweeping gesture towards the microwave and fridge. They were not long in the break room, but after they left her father’s jovial expression had changed.

Because of her father’s warning, Yeye kept her distance from Harriet and also from sweet Debbie Taylor. Sometimes her father’s words about them provided comfort to Yeye, and she cupped his words like she would a firefly, peeking between her thumbs to see if they would glow. When she watched Harriet and her friends from the safety of Aunty Lola’s blue ranch house, her father’s words rang true, and she could see that aside from the brownness of their skin not much else linked her to these girls. She saw how these three chomped on their bubble gum or outlined their mouth with Lip Smackers and how their small, unformed waists swayed to nothing in particular but the lift of their shoes. On the gravel driveway of Harriet’s house, they circulated gossip and swapped bracelets, the colors from their tie-dyed shirts dizzying like Yeye imagined their talk to be. The three wore their hair straightened by relaxers, down or up in a ponytail, and sometimes dangling with rainbow beads that rattled like maracas when they ran. Harriet, the prettiest of the three, had cinnamon skin that looked cocoa-butter soft and accentuated her hair with rows of beads in electric shades of purple. Yeye’s hair was not straightened but coarse like sheep’s wool, lathered with moisturizer and combed on Sunday evenings by her mother, plaited into a style that ran down her scalp mimicking the lines of a naked tangerine. No one would have mistaken Yeye for being one of them.

But when she walked past the whitewashed panels of Harriet Johnson’s quaint two-story home and learned that Harriet’s father worked as a doctor in a geriatric clinic west of Wilmington where her Aunty Lola worked as a nurse, then she thought her father’s words confusing. If her family was better than them, then why did they live in the basement of Aunty Lola’s small blue home? Why did they not have a house of their own? Where Yeye could run in the backyard without Aunty Lola peeking through the blinds calling out, “Ah-ah! Remove your feet from my aknunya!”, if Yeye happened to be standing near the little green garden eggs she grew. When she asked her father this, he said very soon they would have a place of their own,and he opened his arms wide to show how big. Much nicer than Aunty Lola’s place, he said, and without the smell of fried plantains obvious every time she pushed her nose into the cushions. Yeye giggled because that was what she loved the most about Aunty Lola’s house.

“Class, I hope you were paying close attention,” Ms. Edwards said, closing the book. She proceeded to pass out copies of the excerpt she had just read to the class. “Take a copy of the passage and use it to help you on your homework tonight. Please write a paragraph on why you think Papa set fire to his own cotton.” The class groaned. Ms. Edwards was the only teacher still requiring students to complete homework this late in the year.

Ms. Edwards clapped her hands. “Now, who’s ready for recess?” With those words, students scrambled out of their desks, suddenly revived by the opportunity to play in the sunshine. During recess, Yeye and Abena maintained a good distance from Harriet and her friends, choosing to remain close to Ms. Edwards, who stood in the middle of the field like a rotating watchtower. Ms. Edwards sometimes had another teacher or classroom assistant with her, but today she stood by herself. The boys tossed footballs, played freeze tag, and challenged each other to sprints across the field. Yeye watched Harriet and the other black girls playing hopscotch, jumping rope, and engaging in clapping games. She would not admit to anyone that though she disliked Harriet, she longed to trade bracelets and learn the double Dutch routines. She could certainly not share this with Abena, even though they were best friends. Their friendship had bloomed with the swiftness of a daylily, as if subconsciously they knew they needed to bond in order to navigate the perils of Harper Elementary. If she shared her desires with Abena, it might diminish their friendship somehow, make it seem that the other girls had something that Abena did not. Though to Yeye, they did. The other girls possessed a confidence about their lives in a place still foreign to her.

Debbie Taylor played hopscotch with the girls as well. For a while, Debbie had come around Yeye, chatting about homework assignments, asking Yeye if she missed her grandfather in Nigeria, and offering frosted peanut butter cookies. Yeye gave short and monotonous replies to Debbie so that eventually Debbie began to leave her alone. She missed Debbie’s mother—her tinkling Southern voice, charming stories about farm life in Tennessee, and her living room shrine to the then-presidential candidate. Mrs. Taylor once tapped a framed magazine article of the blue-eyed possibility whose lips were curled around a gold saxophone. “Clinton’s all about us black folks,” she said. “Don’t listen to nobody that tell you otherwise. You hear me, Ye?” Mrs. Taylor used to call her “Ye,” often saying she did not see why she needed to repeat herself. Yeye did not understand what Mrs. Taylor meant about Clinton. She wanted to ask her if Clinton would be about Nigerians too, but the crunch of the chocolate chip cookies and the sugar in the strawberry lemonade overshadowed her questions and Mrs. Taylor’s eccentricity. Sometimes she wondered if she could have maintained a school-only friendship with Debbie, away from her father’s watchful eyes, so that she and Abena would not be outsiders looking in on the other girls playing together.

Yeye watched as Harriet threw a stone on the chalk-drawn hopscotch course, laughing and tapping the numbered squares with her purple shoes. Yeye looked down at her own plain white tennis shoes, shoes that by their very nature of being plain drew attention to themselves. With a sigh, she turned to Abena.

“Let’s see if we know the words to one of the clapping games.”

“Okay. Which one?”

“Miss Mary Mack.” Yeye selected the song she could hear from the voices of the girls, which carried from the blacktop to where she and Abena sat.

“I can’t remember all the words,” Abena said.

“Please? I can start,” Yeye said.

They sang together.

Miss Mary Mack, Mack, Mack,

All dressed in black, black, black,

With silver buttons, buttons, buttons,

All down her back, back, back.

She asked her mother, mother, mother...

“For fifty cents, cents, cents,” Abena sang, and because of her lisp the word “cents” sounded like thents.

Yeye interrupted. “It’s not fifty cents. It’s fifteen cents.”

“No, it’s fifty. How can you see an elephant jump for only fifteen cents?”

Yeye said. “It’s fifteen. I know it is.”

They were both quiet. Abena tucked her knees closer to her chest and pulled a couple of dandelions out of the ground. She proceeded to pluck the seeds off two or three at a time instead of blowing them so the seeds could shimmer in the air. Yeye wished that Abena cared about learning the rhymes so that one day if the other girls ever asked them to join, the girls would be impressed by the perfection of their verses and the alacrity of their clapping.

Yeye softened her voice. “I want to know the right words. Don’t you?”

“I don’t care that much,” Abena said. “I don’t like that song.”

Yeye pointed to the blacktop. “Let’s go closer so we can learn it.”

“I don’t know if we should.”

“Please?”

“What if Yamhead says something to us?”

“We won’t get too close. Plus, Ms. Edwards is near.”

Abena bit the nail of her thumb.

“Please?” Yeye pleaded.

“Okay...I’ll come.”

The chorus and clapping of the girls increased with each step. If anything happened, Yeye thought, only nine more days were left in the school year. She would not have to see Harriet and her friends every day until sixth grade began in the fall. Avoiding them in the neighborhood no longer posed a problem. She had determined to never again run into the three, as she did the very first week she explored the neighborhood. The three of them were jumping rope on the sidewalk in front of Harriet’s house. The girls stopped swinging the rope and stared at Yeye as if she were a mongoose with three arms and three legs, their glances resting on her cropped Afro and pink corduroys. She was painfully aware that her corduroys were not like the blue jeans that hugged their legs and folded at the bottom to show off their sneakers. After that incident, she had perfected several routes to avoid Harriet’s house, enduring a labyrinth of streets and backyards to visit Abena’s place.

Nearing the blacktop, Abena hummed Miss Mary Mack under her breath. Yeye was about to join her when she saw scrawny Jeffrey Larsen running, his back towards her, his legs as ungainly as a foal’s, his eyes tracking a football sailing through the air. Panicked, Yeye stopped to let him pass. Jeffrey turned abruptly, as if the ball had shifted mid-course, slamming into Yeye and landing both of them on the grass. Stunned by the fall, Yeye stood up with her palms throbbing where she had tried to brace herself. Jeffrey, on the other hand, had stumbled into a patch of grass still muddy from yesterday’s thunderstorm. Laughter immediately filled the air at the sight of Jeffrey on the ground, his elbows and pants splattered with mud. The boys who had thrown the football pointed, chuckling as well, as if the accident were all part of an elaborate ploy.

“You saw me,” Jeffrey blurted to Yeye.

“It was an accident,” Yeye said.

“No, it wasn’t!” He was up now, his voice rising, fists clenched, his blonde hair disheveled from the fall, obscuring his eyes, the football forgotten.

The laughter of the children increased. Yeye’s lips quivered, and she wondered why Ms. Edwards was not hurrying to where they stood.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I didn’t see you.”

“You did too!”

That’s when it happened.

The word flew out of Jeffrey’s mouth—loud, red, and angry like the rest of him. It erupted with a force that must have come from the tittering and giggling swirling around him. Yeye waited for the other children to burst out in more laughter. It never came. Jeffrey’s word had shattered the air, striking with equivalent sharpness to the cracking of a coconut shell. The students’ mouths were frozen in twisted, silent oh-shapes.

“What’d you say Jeffrey?” Harriet’s voice cut through the thickness of the silence.

“Nothing,” Jeffrey said.

“I heard you.”

“I didn’t say anything.”

“Yes, you did.”

“You can’t prove it,” Jeffrey challenged, glaring at the two of them.

Harriet grabbed Yeye’s hand. “Come on. We’re telling on him.”

“It’s fine,” Yeye said, wondering why Harriet had rushed over from the hopscotch game in her defense.

“No, it’s not,” Harriet said. “Don’t you get it? He can’t call us this.”

Yeye wanted to tell Harriet that Jeffrey’s word meant nothing to her. It was like hearing the word butter and being expected to lash out in anger when butter was nothing more than a lump of muted yellow in a porcelain dish on Mrs. Taylor’s dining table or forgotten on the side of her family’s refrigerator. Simply a new word in the line of insults she did not understand, insults she never heard back home in Jos, insults using phrases or characters that came from American movies or shows she had never seen. Yeye did not say any of this to Harriet. She was afraid that Harriet might release her hand, and the spell that Jeffrey’s word had cast over Harriet would be broken.

Harriet marched over to Ms. Edwards, who sat on the steps consoling a student that hurt her arm. Harriet interrupted without excuse and explained the situation as confidently as she had spelled acknowledgement on stage.

“Are you sure he said it?” Ms. Edwards asked. “This is serious, Harriet.”

Harriet nodded. “I was going to get a drink of water, and I heard him after he fell.”

“Yeye?” Ms. Edwards looked to her for confirmation. “Did he call you this?”

For a moment, Yeye realized that she was in the rare position of holding power over Jeffrey. If she said no, she could let all of this go, this commotion around a word that she did not understand. If she said yes, then inevitably this would lead to something greater than she could control for a word that meant nothing to her. But in that moment, she felt as if no would have been wrong, no would have destroyed a potential friendship with Harriet, no would have been the wrong response for a word that seemed to have such power for Harriet and Ms. Edwards that they could not even repeat it, a word that was supposed to have power over her as well.

“Yes,” Yeye said. “Jeffrey said it.”

Ms. Edwards walked as quickly as her two-inch heels would allow to where Jeffrey stood. The other boys crouched on the field, reenacting the incident, imitating Jeffrey by flinging themselves on the ground. The sight of Ms. Edwards marching towards them broke up the commotion. A few of the students who had witnessed the confrontation were huddled together whispering about the excitement that had just taken place. Abena had withdrawn under the sugar maple tree, where together she and Yeye had sung Miss Mary Mack.

Ms. Edwards returned with Jeffrey. “The three of you come with me,” she said. “We’re all going to the principal’s office.”

Ms. Edwards found a school counselor to monitor the remaining ten minutes of recess and send the children to their next class. Yeye had never been to the principal’s office before. Troublemakers visited Mr. Kilter. The severity of the situation began to dawn on Yeye; she wondered if Jeffrey’s word might be worse than the other names she had been called. Ms. Edwards walked into Mr. Kilter’s office, leaving Yeye, Jeffrey, and Harriet with Mr. Kilter’s secretary. Jeffrey, sullen and reticent, swung his feet back and forth under his chair, his head down. The three of them did not speak to each other. Yeye thought about how Harriet had said us. It seemed Jeffrey’s word was for people like Yeye and Harriet. Were they both this word, or was Yeye alone this word and Harriet had meant something else by us?

One by one, Mr. Kilter brought them into his office to explain their version of the incident. Jeffrey went first and Harriet second. When it was Yeye’s turn, she sat in one of the padded foldable chairs facing Mr. Kilter’s desk. His office was cramped, painted white, and a running trophy stood in one corner with the inscription: University of Delaware, 1973. Though he received the award twenty years ago, Mr. Kilter embodied the physique and exuded the energy of a man who ran several miles every morning. Stacks of blue folders occupied his desk. His two daughters grinned without worry from a family portrait adorning his bookshelf. They looked only a few years older than Yeye, both of them fair-haired like Mr. Kilter and his wife. Next to the bookshelf, a round table supported a small aquarium tank where fan-tailed guppies swam through pebbles and plastic greenery.

In an encouraging voice, Ms. Edwards asked Yeye to explain to Mr. Kilter what happened during recess. Though her ears were warm and she had to swallow to moisten her throat, Yeye recounted how Jeffrey failed to look in her direction, how she stopped to avoid him, and he ended up running into her so that she fell down on the grass.

“Did you hurt yourself?” Mr. Kilter asked, his tone sympathetic.

Yeye shook her head.

“Good.” He paused. “Did you see Jeffrey running towards you?”

“Yes.”

“Why didn’t you move out of his way?”

“I don’t know. He was running too fast.”

“Did you say or do anything to make Jeffrey say this word?” Mr. Kilter asked.

Jeffrey had said the word candidly, bluntly, like opening a can of soup and dumping out the contents. Yet this word, like butter to Yeye, was being delicately handled, cradled in the mouths of adults.

Mr. Kilter leaned on his desk. “Yeye, did you push Jeffrey or call him any names?”

“No,” Yeye said.

“She’s an excellent student,” Ms. Edwards said. “If she says that she didn’t provoke him, I believe her.”

“Ms. Edwards, I have to ask these questions.” Mr. Kilter scratched behind his left ear, a sweat-drenched circle visible in the crease under his arm as he did. He turned to Yeye. “Jeffrey says that you tripped him. Is this true?”

“No.”

“How did you feel after Jeffrey called you this word?”

For a few seconds, Yeye did not respond. Outside Mr. Kilter’s window, she could see the roundabout where the buses dropped and picked up students, the newly planted trees with thin silver wires bracing their trunks, and the school flagpole dividing the sky. The American flag hung limply, unable to flap without a breeze and below it, a white flag with an imprint of Harper’s mascot: a plump blue jay. A chicken, she and Abena had purposefully called it. How could a chicken mascot scare anyone? They laughed about it for days whenever their bus pulled up to the school.

“Yeye?” Ms. Edwards said. “Did you hear Mr. Kilter?”

Yeye nodded. But how could she explain to Mr. Kilter that she had been saddened by how Jeffrey said the word and not the actual word itself?

“How did you feel?” Mr. Kilter repeated.

“I don’t know.”

“Did it bother you?” Mr. Kilter said.

Ms. Edwards interrupted. “Of course it bothered her.”

“This is a serious allegation, Ms. Edwards. We can’t punish one student if another student may have played a role in provoking the other.”

“But Yeye didn’t provoke him.”

“Jeffrey denies saying this word, and he insists that Yeye tripped him. I’m hearing conflicting stories.”

“Neither of these girls would make this up.”

“It’s better if we let this one go,” Mr. Kilter said. “We don’t want to involve parents over an unclear situation that you, unfortunately, did not witness.”

Yeye got the feeling that she had become invisible, folded into the stuffing of the padded chair. If Yeye had not desperately sought to learn the words to the song, she would have avoided the entire situation. If she had listened to Abena and stayed under the tree, ignored the itch to be close to Harriet, to be close to these other girls, then she would not be in the principal’s office. Where were they when Christopher Jenkins called her ugly, when at that time, the pain and embarrassment swallowed her whole, and tears spotted her lilac sweater so it looked as if the glitzy cartoon rabbit itself were crying? Here she was, in trouble for a word that did not sting the same as ugly.

“But Harriet heard him say it,” Ms. Edwards said. “He needs to be punished.”

“We can’t prove this. We either punish both of them or we let it go.”

“Mr. Kilter—”

“Ms. Edwards. You’re reading Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry to your class, correct?”

“Yes.”

“Who’s to say Jeffrey didn’t learn it from this book?”

Ms. Edwards removed her red-rimmed glasses and closed her eyes. Now, it made sense to Yeye, the word that Ms. Edwards whited out in the chapters she gave to the class. The fact that they never had their own copies of the book, but that she chose to read aloud from hers. Yeye admired Ms. Edwards, her full gypsy skirts and jean vests, the way she spoke with authority in the classroom, and how she took care to answer every question students had, relevant or otherwise. She had even sent home a letter to the parents about the book to make sure no parents raised any objections. Yeye’s father had signed the letter, on board with anything that meant additional reading for his daughter. Leaning against the door, Ms. Edwards pulled taut the hem of her jean vest. She put her glasses on again and her eyes seemed smaller, less focused, too bright.

“Yeye,” Ms. Edwards said. “You and Harriet can head to social studies. Tell Jeffrey to come into the office again.”

Mr. Kilter started. “It’s not necessary for Jeffrey—”

“Please, Mr. Kilter, I believe it is.”

Yeye left the room, shutting the door, feeling like she had been part of a conversation she was not supposed to have been privy to. Jeffrey’s thin lips coiled into a smug smile when Yeye told him he was wanted in the office, and Yeye knew she had been right about him all along, his misleading cherubic features and ruddy cheeks. She hated Jeffrey. She had not even known he was capable of catching a football or strong enough to have knocked her down. She remembered with a sort of bitter delight that Jeffrey never ended up with the football in his hands; the other boys would talk about it for days. Yeye blamed Jeffrey for causing her to miss the rest of recess, diminishing the possibility of seeing Christopher Jenkins and having him smile at her. Because sometimes Yeye imagined that if Christopher would just smile at her as he did that first day of school, then all would be fine again.

Harriet and Yeye received two passes from the secretary and headed to their social studies class. As they walked, Yeye studied Harriet’s purple-and-green bracelet and her earrings of interlocking purple circles. She thought Harriet might change back into Yamhead like a butterfly degenerating into the woolly caterpillar it had once been. When she was five, Yeye caught a butterfly in a jar, dropped flower petals and grass inside, and placed it in her family’s backyard. She had waited for days to see if the rules of nature would reverse. But Harriet had not changed back; she was overly curious, eager to know what transpired in Mr. Kilter’s office.

“Yeye, what happened?” Harriet said. The sound of her actual name out of Harriet’s mouth surprised Yeye, since she had grown accustomed to an intentionally mangled pronunciation.

“Nothing,” Yeye said.

“What?” Harriet stopped walking, and Yeye had to turn to face her.

“Jeffrey told Mr. Kilter that I tripped him.”

“But I told Mr. Kilter it wasn’t your fault.”

“It’s okay.”

“No, it’s not. Did you at least cry?”

“No.”

“You should have cried.”

“It doesn’t matter,” Yeye said.

“Yes, it does. My dad told me that no one should ever call me that,” Harriet said. “Don’t they teach you this stuff in Africa?”

Yeye hated these seconds when she was uncertain of what to do or say, an inward dance that she wanted to bow out of each time it happened. Any response could become another weapon in Harriet’s arsenal of insults. She looked at Harriet, butterfly beautiful with her relaxed hair in perfectly aligned pigtails, her purple-and-lime-green outfit, and the privilege of knowing that Christopher Jenkins liked her and found her pretty.

“I don’t know what it means,” Yeye said, finally.

“You should,” Harriet said. “All black people should know what it means.”

Yeye did not respond to Harriet’s matter-of-fact statement. Was Harriet saying that Yeye was black like her? Back home, people talked about if they were Gbagyi, Hausa, Yoruba, Oron, Igbo, or Ijaw. They talked about if they were from the Northeast or the Southwest. They talked about the states in which they were born, if they hailed from Plateau, Benue, Nassarawa, Ogun, or Cross River State. Back home, people were light and dark-skinned, the varying shades of the groundnut, kola nut, and tiger nut. Harriet did not eat pounded yam with egusi soup or kneel for her elders as Yeye had been trained to do. How then could Yeye be like her? Her father’s polarizing admonition churned in her ears, his words about who she was and who they were, and how they were not at all the same.

“We have to protest,” Harriet said.

“What?”

“When white people wouldn’t let black people eat in their restaurants, black people protested.”

Yeye remained silent.

Harriet continued. “My dad said all the black people got together and went into the restaurant. They waited for someone to ask them what they wanted to eat, but nobody did. They got called all sorts of bad names and were kicked out. Sometimes you still have to protest even if it doesn’t work.”

“I don’t want to protest.”

“You have to stand up for yourself. Jeffrey lied. It’s not fair.”

Yeye was satisfied with Mr. Kilter’s decision to let the situation end, to not draw it outand involve her parents. Her father and mother had warned her against fighting and bringing attention to herself in this new place. She did not want her father to be called to the school to discuss a word that had never made an appearance in their home. She imagined her father sitting in Mr. Kilter’s office for a parent-teacher conference with an indecipherable expression on his face. Only Yeye would know that he was wondering why she had been busy running into boys on the playground rather than staying to herself and concentrating on her schoolwork, wondering why the school called him in to discuss trivialities and not his daughter’s stellar academic performance or student-of-the-month award.

“C’mon, Yeye, let’s protest,” Harriet said.

“I don’t care anymore,” Yeye said.

“You have to care.”

“No, I don’t.”

“What’s wrong with you?” Harriet said.

“You call me names all the time.”

“But this one’s worse!”

“No, it’s not! Yours are worse!”

The two girls stared at each other. Yeye had not meant to shout. She could have never before envisioned shouting at Harriet, but the words had boiled over, out of her frustration. She felt herself drowning with Harriet pressing her views upon her and rambling on about protesting.

“Girls, where are we going?” It was the hall monitor. They showed her their passes, and she snapped her fingers. “Well, let’s hurry it along.”

“You’re so weird,” Harriet said, when the hall monitor could no longer hear them. “You’re black. You should be mad.”

“I’m not black,” Yeye said.

“What?” Harriet said.

“I’m not black.”

Harriet scoffed. “Yes, you are. You look just like me. You’re black.”

“No, I’m Nigerian. It’s different.”

Harriet laughed. “How?”

“I don’t know. It just is.”

“You think you’re better?” Harriet’s arms were crossed.

“No,” Yeye said.

“Whatever then, you’re black.”

“No, I’m not.”

“Yes, you are!”

“No, I’m not!”

“Yes, you are!”

“I’m not black! I’m not!”

“You are too, Yin Yang!”

Harriet stormed off down the hallway, past the gigantic school banner draped near the double doors, and disappeared around the corner. Yeye touched the ends of her plaits, dry-tipped and curled, held in place with tiny rubber bands to prevent them from unraveling. The heat from the confrontation with Harriet rushed to her fingertips, and she thought this must have been what Cassie experienced with Lillian Jean. At first, Yeye had wanted to preserve the surprising development with Harriet. That Yamhead Harriet Johnson, of all people, had come to her defense. But now she suddenly wanted to be very far from Harriet.

Walking down the hall, Yeye repeated Jeffrey’s insult. When she said it, the tip of her tongue touched her two front teeth, and the last syllable came out as if she were gagging or struggling to breathe. She tried to let it roll on her tongue. This word like butter was not a word that rolled like butter. It was one that stuck, like a piece of grape taffy plastered to the roof of her mouth, like a chestnut burr that hooked itself to her shirt. Not until she was a few feet from Mrs. Royce’s classroom did Yeye realize she had forgotten her social studies book in Ms. Edwards’s class. She turned in the opposite direction and hurried down the hallway. She would not retrieve Harriet’s book for her. It served Harriet right for running off.

“It’s my fault,” Yeye heard Ms. Edwards say when she neared the classroom. “The book was too advanced for them.”

“You can’t blame yourself,” another voice said. “The teachers on your team signed off on your selection.”

“But Kilter dismissed the whole incident.”

“It’s done now. Just be careful next time.”

“I don’t know where Jeffrey learned it. I skipped over it every time.”

“Bridget, I’m sure he’s heard it somewhere else before. What’s his punishment?”

“Nothing, just a talking to by me. I told him never to repeat that word again if he said it, which I’m pretty sure he did.”

“Everything will be fine. You’ll see.”

“She’s a young, black girl,” Ms. Edwards said. “What if she thinks about this for the rest of her life?”

The other person laughed. “Honey, this is your first year teaching, right? She’ll get over it. There’ll be something else to worry about tomorrow.”

“I didn’t get over it when it happened to me.”

“But you turned out just fine, right?”

There was a pause.

“I’ll talk to her tomorrow,” Ms. Edwards said.

Yeye did not go inside or knock on the door as she had intended. From the sound of it, Ms. Edwards might insist on talking to her if she entered the classroom, and Yeye had never wanted a school day to be over as desperately as she wanted this one to end. She did not want to hear the same confirmation of blackness from Ms. Edwards’s mouth as she had from Harriet just minutes ago. But to accept her blackness might lead to acceptance from Harriet. She thought about what it could mean for the summer if she and Abena became friends with the three: jumping rope, clapping games, trading bracelets and colorful beads, a straightforward path to Abena’s house. If she agreed to protest, would the teasing cease? Still, Yeye did not want to be akata in the way her father described. Her father said blacks were a people taken so long ago from Africa that many were unable to trace the ethnic groups to which they once belonged. Yeye did not want people to erase her history and culture and replace it with one that was not her own. It seemed that blackness had been something she could not choose to be, something ascribed to her when the plane landed in the Wilmington-Philadelphia Regional Airport, the customs official secretly stamping her passport: Black.

To her family, she was Yeye, their Gbagyi daughter. But did that matter when life could not be lived solely in the confines of her home? To Ms. Edwards, she was black. To Jeffrey, she was black. To Harriet, she was black. To Mr. Kilter, she was black. She thought about the people she saw regularly: the woman in the laundromat where her mother washed their clothes, the cashiers at the Asian market where Aunty Lola bought her Maggie cubes, the bus driver that greeted her each morning as she climbed the steps. Did they too see her as black?

Yeye thought how the world had been a little more right, the sky a little more clear, just sitting with Abena against the unyielding trunk of the sugar maple tree. Yeye brightened and quickened her pace. Abena would tell Yeye what she wanted to hear. Yeye would tell Abena all about what Harriet and Ms. Edwards said. That’s not true, Abena would say, you’re Nigerian, just like I’m Ghanaian. And Yeye hoped that Abena would not giggle before saying those words. Then they could finish singing the rest of Miss Mary Mack without a care about how much it cost to see the elephant jump over the fence. For a moment, Yeye would not have to worry about where she belonged, about who she was to everyone she encountered. In that moment, she would only have to worry about knowing the words to the rest of the song.

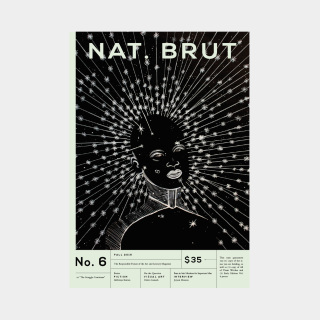

Nat. Brut Issue Six

Issue Six is our second in print, and features work by Cristina de Middel, Afabwaje Kurian, Chitra Ganesh, Jayson Musson, and more! Issue Six also comes with limited edition supplements: All of Them Witches, a 32-page risograph-printed comic re-interpreting 1950s Harvey Horror comics, plus volume four of our comics section, Early Edition!