< Back to Issue Two: Table of Contents

[Essay]

POSTER CHILD

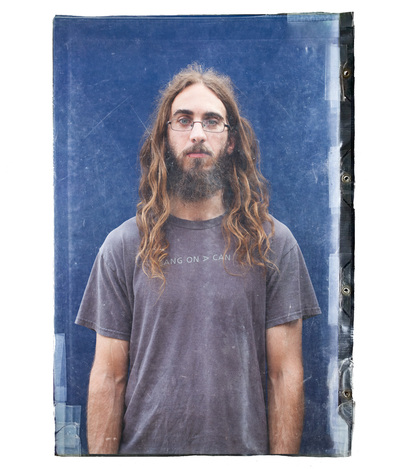

by Erin Sheehy with photographs by Michael DePasquale

We visited the University at Buffalo in early September; the weather had already begun to turn and the students were nearly out of spending money. It was raining and the sale was taking place under a big white tent in the middle of a soggy field; the posters were wavy with humidity. A boy wearing his student ID on a lanyard and a “Make Love, Not War” button on his t-shirt bought a Pulp Fiction poster. He hesitated by the doorway, where heavy raindrops were splattering off the roof of the tent, making pockmarks in the mud below. Outside, a group of students huddled around the POSTER SALE sign. “Why would we need posters?” I overheard one boy say. “We have porn.”

In a world of carefully curated and constantly updated online personas, where teenagers with tumblrs are fluent in the language of advertising and attuned to the slightest nuance of trend and subculture, the dorm room poster seems embarrassingly crude. But we still inhabit the material world, and for students unfortunate enough to live on campus, it is a dull and ugly place. When you finally shut your laptop, crawl into your twin cot or your top bunk, and stare up at the cold grey walls of your carpeted cell, you will want something pleasant to look at. You will want to see some little reflection, however faint, of yourself.

And so there are poster sales, held in quads and commons and halls across the nation, from the Christian schools that censor Big Bang Theory promo posters and Boticelli’s The Birth of Venus to the West Coast universities where fraternity pledges buy pictures of models in lacy bras and Mardi Gras beads leaning seductively over beer pong tables. COLLEGE: TWO RACKS, TWO BALLS, ONE HISTORIC NIGHT.

Though there is a lively tradition of posters that celebrate “college life” as envisioned by a certain type of 18-year-old boy—diagrams of beer pong racks, porn stars holding textbooks, and of course John Belushi with his bottle of Jack Daniels—college posters do not constitute a “type.” They have no cohesive aesthetic. The history of the modern poster is short but sprawling—from the French Masters and their Moulin Rouge ladies to World War II propaganda to Day-Glo concert ads—and the college market has swallowed it all. We now have a stable of disparate images that, stripped of their contexts, have become clichés of college life, pieces like Steinlen’s Le Chat Noir ad and the naked ladies with the Pink Floyd albums painted on their backs. The dorm room poster even has its own canon of artists, people like M.C. Escher, Salvador Dalí, and Ralph Steadman, revered by freshman discovering the joys of psychedelics.

At UB, the posters were kept inside of large display books and organized by type. Most categories were straightforward: music, movies, TV shows, sports. Other posters were grouped together because they were thought to appeal to a certain kind of person. Flipping through the “romantic” display book I found images of couples kissing, babies, babies kissing, Johnny Depp, flowers, kittens, kittens kissing, giraffes kissing, baby animals with their moms, baby penguins, and penguins holding hands. “These are the posters,” a saleswoman said, “for the girls who like Hello Kitty.”

It’s hard to be articulate about the things you like, and even harder to be articulate about the things you buy. When we asked the students we photographed why they’d bought the posters that they did, they had little to say. The only people who were vocal about their taste were the ones trying to persuade roommates:

“I love Starry Night, but I don’t think those are our colors.”

“Are we really just going to have a map on the wall?”

“Oh I get it,” said a salty dance major who stood for one of our portraits, “this is, like, a project on identity.” She had just bought a poster of Bob Marley and another of naked bodies arranged into a peace sign. “Well apparently I’m a sex-crazed drug addict.” In this era of the “expert consumer,” when our identities are tied ever closer to our tastes, our purchases are supposed to say something about the type of people we are. But spend a day watching dozens of kids buy the same ALL HAIL THE KING promo poster from Breaking Bad, and you start to wonder how much someone’s favorite TV show can say about them. If it’s easy for my generation to look back and laugh at our freshman year Tupacs, our black-light Led Zeppelins, and our Tables of Mixology, it’s because they reveal very little about who we are, or who we used to be. They do, however, say something about the way we once presented ourselves to the people around us.

When Facebook introduced its Timeline format, I immediately deleted years of information, less terrified of confronting my 18-year-old self than of meeting the person my 18-year-old self tried to be. Facebook, a service initially available only to college students, uses the dorm room as its model. People post things to their walls, and the stuff that shows up there is not unlike the stuff a college student might tack to the bulletin board above her bed: flyers for shows, notes from friends, photos where she looks prettier and more fun than usual, her own writings/drawings/awards. This isn’t to say that the Facebook wall is merely an extension of the dorm room or that dorm room décor is merely an analog way of showing off. But they share the same conceit: that we are letting people into our private worlds, when we know that we are putting our tastes on display.

Dorm rooms and university apartments are, in some sense, public spaces. You often share your cramped quarters with strangers. People you do not like and do not know enter all the time. Your room is subject to routine inspection. Institutional regulations prevent the most creative decorating: paint, nails, candles and custom furniture are all prohibited. “We have many customers,” said one poster saleswoman, “who say the dorms are so ugly, they just want to fill them with images.” The poster serves as a placeholder, perfectly suited to this transitional housing. People have a habit, when they pack up and move out, of leaving their posters hanging.

The day after the storm cleared, UB held a campus safety fair. Students were given fire extinguisher lessons, local law enforcement showed off a bomb-disabling robot, and in the quad outside the student union, firefighters staged a controlled burn of a model dorm room. Built inside of a box truck, the dorm room was jarringly accurate, with its crowded desk, messy twin bed, and tattered V-J Day in Times Square poster. It was destroyed in mere minutes. While the crowd stood with their phones raised over their heads, taking photos, the plume of smoke grew thicker and darker, until finally the firefighters quelled the flames with their power hoses, leaving a steaming black hull in the middle of the throng of students.

When I lived in the dorms during my freshman year of college, the fire alarm sounded constantly. We always took our time to evacuate, grumbling about people who didn’t know how to fucking microwave popcorn, and we never took anything with us.

[Essay]

POSTER CHILD

by Erin Sheehy with photographs by Michael DePasquale

We visited the University at Buffalo in early September; the weather had already begun to turn and the students were nearly out of spending money. It was raining and the sale was taking place under a big white tent in the middle of a soggy field; the posters were wavy with humidity. A boy wearing his student ID on a lanyard and a “Make Love, Not War” button on his t-shirt bought a Pulp Fiction poster. He hesitated by the doorway, where heavy raindrops were splattering off the roof of the tent, making pockmarks in the mud below. Outside, a group of students huddled around the POSTER SALE sign. “Why would we need posters?” I overheard one boy say. “We have porn.”

In a world of carefully curated and constantly updated online personas, where teenagers with tumblrs are fluent in the language of advertising and attuned to the slightest nuance of trend and subculture, the dorm room poster seems embarrassingly crude. But we still inhabit the material world, and for students unfortunate enough to live on campus, it is a dull and ugly place. When you finally shut your laptop, crawl into your twin cot or your top bunk, and stare up at the cold grey walls of your carpeted cell, you will want something pleasant to look at. You will want to see some little reflection, however faint, of yourself.

And so there are poster sales, held in quads and commons and halls across the nation, from the Christian schools that censor Big Bang Theory promo posters and Boticelli’s The Birth of Venus to the West Coast universities where fraternity pledges buy pictures of models in lacy bras and Mardi Gras beads leaning seductively over beer pong tables. COLLEGE: TWO RACKS, TWO BALLS, ONE HISTORIC NIGHT.

Though there is a lively tradition of posters that celebrate “college life” as envisioned by a certain type of 18-year-old boy—diagrams of beer pong racks, porn stars holding textbooks, and of course John Belushi with his bottle of Jack Daniels—college posters do not constitute a “type.” They have no cohesive aesthetic. The history of the modern poster is short but sprawling—from the French Masters and their Moulin Rouge ladies to World War II propaganda to Day-Glo concert ads—and the college market has swallowed it all. We now have a stable of disparate images that, stripped of their contexts, have become clichés of college life, pieces like Steinlen’s Le Chat Noir ad and the naked ladies with the Pink Floyd albums painted on their backs. The dorm room poster even has its own canon of artists, people like M.C. Escher, Salvador Dalí, and Ralph Steadman, revered by freshman discovering the joys of psychedelics.

At UB, the posters were kept inside of large display books and organized by type. Most categories were straightforward: music, movies, TV shows, sports. Other posters were grouped together because they were thought to appeal to a certain kind of person. Flipping through the “romantic” display book I found images of couples kissing, babies, babies kissing, Johnny Depp, flowers, kittens, kittens kissing, giraffes kissing, baby animals with their moms, baby penguins, and penguins holding hands. “These are the posters,” a saleswoman said, “for the girls who like Hello Kitty.”

It’s hard to be articulate about the things you like, and even harder to be articulate about the things you buy. When we asked the students we photographed why they’d bought the posters that they did, they had little to say. The only people who were vocal about their taste were the ones trying to persuade roommates:

“I love Starry Night, but I don’t think those are our colors.”

“Are we really just going to have a map on the wall?”

“Oh I get it,” said a salty dance major who stood for one of our portraits, “this is, like, a project on identity.” She had just bought a poster of Bob Marley and another of naked bodies arranged into a peace sign. “Well apparently I’m a sex-crazed drug addict.” In this era of the “expert consumer,” when our identities are tied ever closer to our tastes, our purchases are supposed to say something about the type of people we are. But spend a day watching dozens of kids buy the same ALL HAIL THE KING promo poster from Breaking Bad, and you start to wonder how much someone’s favorite TV show can say about them. If it’s easy for my generation to look back and laugh at our freshman year Tupacs, our black-light Led Zeppelins, and our Tables of Mixology, it’s because they reveal very little about who we are, or who we used to be. They do, however, say something about the way we once presented ourselves to the people around us.

When Facebook introduced its Timeline format, I immediately deleted years of information, less terrified of confronting my 18-year-old self than of meeting the person my 18-year-old self tried to be. Facebook, a service initially available only to college students, uses the dorm room as its model. People post things to their walls, and the stuff that shows up there is not unlike the stuff a college student might tack to the bulletin board above her bed: flyers for shows, notes from friends, photos where she looks prettier and more fun than usual, her own writings/drawings/awards. This isn’t to say that the Facebook wall is merely an extension of the dorm room or that dorm room décor is merely an analog way of showing off. But they share the same conceit: that we are letting people into our private worlds, when we know that we are putting our tastes on display.

Dorm rooms and university apartments are, in some sense, public spaces. You often share your cramped quarters with strangers. People you do not like and do not know enter all the time. Your room is subject to routine inspection. Institutional regulations prevent the most creative decorating: paint, nails, candles and custom furniture are all prohibited. “We have many customers,” said one poster saleswoman, “who say the dorms are so ugly, they just want to fill them with images.” The poster serves as a placeholder, perfectly suited to this transitional housing. People have a habit, when they pack up and move out, of leaving their posters hanging.

The day after the storm cleared, UB held a campus safety fair. Students were given fire extinguisher lessons, local law enforcement showed off a bomb-disabling robot, and in the quad outside the student union, firefighters staged a controlled burn of a model dorm room. Built inside of a box truck, the dorm room was jarringly accurate, with its crowded desk, messy twin bed, and tattered V-J Day in Times Square poster. It was destroyed in mere minutes. While the crowd stood with their phones raised over their heads, taking photos, the plume of smoke grew thicker and darker, until finally the firefighters quelled the flames with their power hoses, leaving a steaming black hull in the middle of the throng of students.

When I lived in the dorms during my freshman year of college, the fire alarm sounded constantly. We always took our time to evacuate, grumbling about people who didn’t know how to fucking microwave popcorn, and we never took anything with us.