INTERVIEW - ISSUE FIVE

Show Me Something Beautiful

AN INTERVIEW WITH MERRITT TIERCE

By Kayla E.

* * *

KE: Can you reflect on your earliest experiences with literature and/or art, and how they influenced your thought processes?

MT: The literature I was most immersed in as a child was the Bible, although until I was in my early twenties I would have thought the categorization of that book as literature a severe demotion, if not heretical. Given the violence of the Old Testament and the propensity of evangelicals to exalt notions of self-abasement, it’s not hard to see how my thought processes thus came to be suffused with a general doom. I had an early, perhaps even preverbal, introduction to the conflicting ideas that humanity is inherently corrupt and yet miraculously salvageable. Everything I’ve written so far embraces the former and questions the latter, even though I’m no longer religious.

A habit of mind I often turn to is the consideration of ideas writ large. If something is true in proportion to the truth of something else, I try to zoom out and see how it looks from outer space. Is it still true to the same degree, and in the same relation to the other truth? That is, if I extrapolate one instance of a belief I’m testing, does it hold at any scale? Or what does it mean if you look at it from way way back? What else do I learn about that particular truth when I’m so close I can see each pixel, or so removed I can barely tell how it’s different from any other?

When I subject those conflicting ideas I mentioned, which were implanted in me almost from birth, to such an exam, at this moment in my life “inherently corrupt” reads as “tending toward death,” which makes sense to me. All life tends toward death. All life contains within it an eventual, incontrovertible fact of death—an intrinsic bias toward breaking down, whether that manifests as an injury, a lie, a crime, a bad decision, or some other failing. And “miraculously salvageable” reads as “denying death,” which is to say fantastical. But also—driven to such extreme lengths to sustain itself and its idea of itself.

Motorcycle (24 years old), Fall 2003

Motorcycle (24 years old), Fall 2003

These are fairly staid, supercilious views of the function of religion— that it is a comfort, an organizing matrix for sentient, big-brained animals who are both bound to end and as intent on warding off that end as any other form of life. And these views are also evidence that logic has had as much of an impact on my thought processes as any beat of literature or art.

KE: What sort of stories/whose writing do you respond to?

MT: I respond to beautiful sentences. And to the kind of serious playfulness one finds in the work of Kay Ryan and Lydia Davis—that fluent capsizing of what is known, the adrenaline rush of drowning temporarily, the high of finding oneself right side up in an entirely different world. I adore Grace Paley with every bit of my ever-loving being. Didion, O’Connor, and Gaitskill go without saying. Gayl Motherfucking Jones. Carson McCullers kills me. So the unsurprising theme is Badass Women. My latest discovery is a contemporary writer, Elisa Albert, whose new book After Birth is the best I’ve read in years. Sentence after sentence made of blood and lightning. You get to the end and all that’s behind you is scorched earth, a whole mountain of dross burned off and just one strange beautiful tree of pure gold left standing.

KE: What sort of stories/whose writing do you respond to?

MT: I respond to beautiful sentences. And to the kind of serious playfulness one finds in the work of Kay Ryan and Lydia Davis—that fluent capsizing of what is known, the adrenaline rush of drowning temporarily, the high of finding oneself right side up in an entirely different world. I adore Grace Paley with every bit of my ever-loving being. Didion, O’Connor, and Gaitskill go without saying. Gayl Motherfucking Jones. Carson McCullers kills me. So the unsurprising theme is Badass Women. My latest discovery is a contemporary writer, Elisa Albert, whose new book After Birth is the best I’ve read in years. Sentence after sentence made of blood and lightning. You get to the end and all that’s behind you is scorched earth, a whole mountain of dross burned off and just one strange beautiful tree of pure gold left standing.

First Author Photo (28 years old), 2008

First Author Photo (28 years old), 2008

The most brilliant storytelling happening now is in television. The writing gets better and better. I never watched television until about four years ago, and today there’s such a feast. The Wire, Breaking Bad, Top of the Lake, The Hour, The Divide. My new favorite is The Knick, which is so well done. It will blow your shirt off. Masters of Sex. I’m in love with Lizzy Caplan. Halt & Catch Fire, Black Mirror, The Code. The Code is Australian and I’d be surprised if it found an American distributor any time soon, but it’s great.

I hate that American studios keep remaking foreign shows that were so much better in their original runs. Forbrydelsen, the Danish show that AMC’s The Killing is based on, is hands down superior to the remake, as is Bron/Broen, the Danish/Swedish show The Bridge is based on. The detective who plays the star of Bron/Broen is one of the most inventive, compelling characters I’ve ever come across. Most inscrutable of all in this inferior-remake-rash is that of Broadchurch, since it was originally an English-language show. With the others I sort of understand the Americans-don’t-read-subtitles explanation, but not only is Broadchurch in English they didn’t even bother to recast David Tennant’s character with an American actor.

I hate that American studios keep remaking foreign shows that were so much better in their original runs. Forbrydelsen, the Danish show that AMC’s The Killing is based on, is hands down superior to the remake, as is Bron/Broen, the Danish/Swedish show The Bridge is based on. The detective who plays the star of Bron/Broen is one of the most inventive, compelling characters I’ve ever come across. Most inscrutable of all in this inferior-remake-rash is that of Broadchurch, since it was originally an English-language show. With the others I sort of understand the Americans-don’t-read-subtitles explanation, but not only is Broadchurch in English they didn’t even bother to recast David Tennant’s character with an American actor.

KE: What do you want to see more of in literature? Less of?

MT: Less of Brooklyn and marriage. Nothing against either, and really by Brooklyn I mean the affluent masquerading as if they weren’t, which isn’t fair. The masquerade isn’t fair, but I also mean it isn’t fair of me to dispense with everyone in Brooklyn like that. It just seems that what is published, in contemporary American fiction especially, is a myopically distorted view of reality. It’s too straight, and I mean square as much as I mean anything about sexual orientation. But it is definitely also too cis-het. And too white. We are fortunate here in Dallas to have a new independent press, Deep Vellum, working really hard to translate the magnificent and possibly less-square works of writers we’d likely never know about or read in English. I’d like to see more of that kind of intentional, deeply thought-out endeavor. I’d also like to see more writers supporting themselves—interested in, encouraged to, and able to support themselves—with work that falls outside of the academy. The shunting of all the writers down the teaching chute dilutes the collective experience bank and the books become shallower, less relevant to anyone but other such chute-shunted writers. That may sound harsh, so let me disclaim that the people who have had the most tremendous influence on my life and my being have all been teachers. I would not be the specific person I am without them, and I value that beyond words—which I mean literally, because I wouldn’t have these very words I’m now writing, if I hadn’t first had the benefit of being taught by exceptional teachers.

All I want to say to someone who wants to write and is trying to figure out how to eat is this: Don’t assume you have to teach. By all means, teach if you love teaching, because we need you. But if you don’t have an urgent desire to teach, instead go do something wild and hard while you’re young and unfettered. Do something complex or intricate that not many people do, and then write about it. Those are the books I want to read.

KE: Are there currently any young female writers you can recommend?

MT: Madhuri Vijay. She’s a comet coming our way, so set up your lawn chairs now and watch her all the way in.

MT: Less of Brooklyn and marriage. Nothing against either, and really by Brooklyn I mean the affluent masquerading as if they weren’t, which isn’t fair. The masquerade isn’t fair, but I also mean it isn’t fair of me to dispense with everyone in Brooklyn like that. It just seems that what is published, in contemporary American fiction especially, is a myopically distorted view of reality. It’s too straight, and I mean square as much as I mean anything about sexual orientation. But it is definitely also too cis-het. And too white. We are fortunate here in Dallas to have a new independent press, Deep Vellum, working really hard to translate the magnificent and possibly less-square works of writers we’d likely never know about or read in English. I’d like to see more of that kind of intentional, deeply thought-out endeavor. I’d also like to see more writers supporting themselves—interested in, encouraged to, and able to support themselves—with work that falls outside of the academy. The shunting of all the writers down the teaching chute dilutes the collective experience bank and the books become shallower, less relevant to anyone but other such chute-shunted writers. That may sound harsh, so let me disclaim that the people who have had the most tremendous influence on my life and my being have all been teachers. I would not be the specific person I am without them, and I value that beyond words—which I mean literally, because I wouldn’t have these very words I’m now writing, if I hadn’t first had the benefit of being taught by exceptional teachers.

All I want to say to someone who wants to write and is trying to figure out how to eat is this: Don’t assume you have to teach. By all means, teach if you love teaching, because we need you. But if you don’t have an urgent desire to teach, instead go do something wild and hard while you’re young and unfettered. Do something complex or intricate that not many people do, and then write about it. Those are the books I want to read.

KE: Are there currently any young female writers you can recommend?

MT: Madhuri Vijay. She’s a comet coming our way, so set up your lawn chairs now and watch her all the way in.

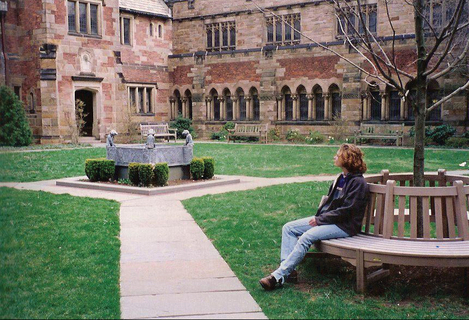

Visting Yale (had been accepted at

Yale Divinty School), New Haven, CT, Spring 1999

Visting Yale (had been accepted at

Yale Divinty School), New Haven, CT, Spring 1999

KE: Can you talk a bit about your personal trajectory as a writer? Did you always want to write?

MT: Trajectory implies direction, arc, and I don’t know that I have any sense of where I am yet. I did always want to write, but the publishing part is an entirely different set of mercurial forces. I can say that for most of my life I was just a reader, someone in love with beautiful language and aware of her own above-average ability to write. Without any concrete idea of how to be a writer, whatever that means.

I was also always intent on not using my ability to write in a way that didn’t arise from pure pleasure. So I didn’t try to get a job teaching creative writing or English lit. I didn’t try to get a job writing copy or doing some kind of technical writing or marketing or any of the things writers can do professionally. I think a lot of that was just fear that I’d kill it, whatever it was that made writing so profound to me; regardless, I feel good about the way it has played out.

My trajectory owes so much more to the people who were generous with me than it does to any feat of mine, though. I feel very lucky to have had the mentorship of Ben Fountain, first among many others. “It should be a source of joy,” he said to me. “A story doesn’t have to do everything,” he said. “Keep writing,” he said. So I did.

MT: Trajectory implies direction, arc, and I don’t know that I have any sense of where I am yet. I did always want to write, but the publishing part is an entirely different set of mercurial forces. I can say that for most of my life I was just a reader, someone in love with beautiful language and aware of her own above-average ability to write. Without any concrete idea of how to be a writer, whatever that means.

I was also always intent on not using my ability to write in a way that didn’t arise from pure pleasure. So I didn’t try to get a job teaching creative writing or English lit. I didn’t try to get a job writing copy or doing some kind of technical writing or marketing or any of the things writers can do professionally. I think a lot of that was just fear that I’d kill it, whatever it was that made writing so profound to me; regardless, I feel good about the way it has played out.

My trajectory owes so much more to the people who were generous with me than it does to any feat of mine, though. I feel very lucky to have had the mentorship of Ben Fountain, first among many others. “It should be a source of joy,” he said to me. “A story doesn’t have to do everything,” he said. “Keep writing,” he said. So I did.

KE: To what extent does the reader’s perception of/reaction to your work matter to you?

MT: Not at all. I don’t think about the reader when I’m writing. Or rather, I’m writing for one reader: me. If I can please myself, that’s the charge I’m going for. Not that it isn’t electric when Ben Fountain or Cristina Henríquez or Carrie Brownstein or St. Vincent or Roxane Gay says your work is the bomb. Of course that matters and of course it feels amazing. But I don’t make what I make by holding my idea of their idea of what they want my ideas to be in my head as I write from word to word. That’d be impossible.

And if I heard that someone I respected thought my latest effort was milquetoast I’d be stung. Sure. I’d cry embarrassed tears in the shower like anyone else. But then I’d go back to read what I wrote, whatever it was that didn’t do it for that particular reader, and I’d forget about them. If it’s out in the world that means I myself led it out into the world because I thought it was so beautiful, and no one else’s opinion can change that.

MT: Not at all. I don’t think about the reader when I’m writing. Or rather, I’m writing for one reader: me. If I can please myself, that’s the charge I’m going for. Not that it isn’t electric when Ben Fountain or Cristina Henríquez or Carrie Brownstein or St. Vincent or Roxane Gay says your work is the bomb. Of course that matters and of course it feels amazing. But I don’t make what I make by holding my idea of their idea of what they want my ideas to be in my head as I write from word to word. That’d be impossible.

And if I heard that someone I respected thought my latest effort was milquetoast I’d be stung. Sure. I’d cry embarrassed tears in the shower like anyone else. But then I’d go back to read what I wrote, whatever it was that didn’t do it for that particular reader, and I’d forget about them. If it’s out in the world that means I myself led it out into the world because I thought it was so beautiful, and no one else’s opinion can change that.

Morning Sickness (did not matriculate due

to unplanned pregnancy), Summer 1999

Morning Sickness (did not matriculate due

to unplanned pregnancy), Summer 1999

KE: Outside of being a creative endeavor, did Love Me Back serve a larger function for you?

MT: When the book sold at auction, which sounds like a fast talking high stakes affair but is actually just a lot of checking your email, my first thought was: Jesus Christ that was all worth something. (‘That’ being all of the personal experiences I drew from.) Which was not a thought I was expecting. It’s not like I was specifically hoping/thinking “If I sell this book, that will magically alchemize my degrading, self-destructive past into money, possibly even ART!” It was just a realization that hit me out of nowhere. I was blindsided by relief.

Writing Love Me Back also revealed to me what I know. One of the truest—to my own experience, anyway--statements about writing I’ve ever read is that one: Flannery O’Connor’s “I write to discover what I know.” My husband, my ex-husband, my kids, my close friends—anyone who has had to converse with me frequently—will attest that it takes me a maddeningly long time to complete a spoken sentence. I’ll say a couple words and pause so long the other party thinks maybe I’ve forgotten we were talking. But it’s just that my default orientation toward all of life is uncertainty. I assume I don’t know. I could probably never arrive at “beyond a reasonable doubt,” about anything (see! I said probably never, and I wasn’t even trying to be clever!). There’s always room for new information, new realities. So it takes me forever to find my way to a collection of words that feels stable enough to send out of my mouth. But writing is different. It’s a more direct transmission of thought.

Love Me Back told me what I thought and felt and knew about all kinds of things. I wrote my own Bible, in a sense. It holds the keys to so many codes I’m just beginning to decipher. And publishing it has brought so many wonderful new people into my life, which again makes me feel like I did miraculously salvage something that was inherently corrupt.

KE: What is your relationship to Texas?

MT: I hated being from Texas until I moved away. Then I became fond of it. I do think it’s too big. It should probably be about five states, and then maybe the aggregate politics of the states-formerly-known-as-Texas would be slightly less deranged.

KE: What is your relationship to Texas?

MT: I hated being from Texas until I moved away. Then I became fond of it. I do think it’s too big. It should probably be about five states, and then maybe the aggregate politics of the states-formerly-known-as-Texas would be slightly less deranged.

|

KE: How did you end up living in Denton, TX?

MT: We lived in Denton the summer I was seven, so my mother could finish her graduate degree in library science at the University of North Texas. My dad bought us two mall gerbils who were both supposed to be female but produced a litter of transparent peanuts a few weeks later. The male had eaten half of them by the time we discovered the reproduction. I lived in Denton again the summer after my freshman year of high school, to attend a geometry camp, during which I may have been molested by three different counselors. I returned to Denton for what would have been my junior and senior years of high school—I enrolled in a magnet school called the Texas Academy of Math and Science. Through TAMS I lived in a dorm on campus at UNT and attended regular college classes, and may have been raped by my first boyfriend. If my references to sexual trauma seem flippant or sensationalist, it’s only because I don’t know what to make of them. Whatever the experiences were, they were formative and I associate them with Denton. When I graduated from TAMS I left Denton to finish my bachelor’s degree, but two years later I ended up back there with my first husband. I was 19, unexpectedly pregnant and unexpectedly married, already in possession of a bachelor’s degree at an age when most kids haven’t decided on a major. But that didn’t mean I knew how to get a job, or what to do with myself, or how to be a mother or a wife. We couldn’t afford for my husband to finish his college degree at the private university where we met, and our families were both in the D/FW metroplex so he transferred to UNT. We divorced after four years, and I moved to Dallas. He stayed in Denton, and because I worked nights the kids lived with him during the week and went to school in Denton. I lived in Dallas for five years and then moved to Iowa to attend the Writers’ Work shop. For most of the time I lived in Dallas, I had my kids every weekend, which meant a lot of driving, meeting their dad halfway at gas stations. |

When I graduated from Iowa and was preparing to move back to Texas, I just didn’t want to have to drive to see them. I didn’t want to have to drive, period. I hate driving. So I moved back to Denton yet again. I didn’t really know anyone there any longer, but I met my second/current husband shortly after my latest return. Since our three kids go to school here and there are two other households involved (his ex and mine), we will probably be in Denton for awhile.

Long story short, I don’t know. I keep getting sucked back for one reason or another. Which isn’t all bad—Denton has much more soul than any other suburb in North Texas. Some interesting, awesome stuff happens in Denton. I just miss living in a city.

Long story short, I don’t know. I keep getting sucked back for one reason or another. Which isn’t all bad—Denton has much more soul than any other suburb in North Texas. Some interesting, awesome stuff happens in Denton. I just miss living in a city.

Young mother recently divorced (24 years old), Fall 2003

Young mother recently divorced (24 years old), Fall 2003

KE: What do you do in your spare time?

MT: Not to sound like the landed gentry or anything, but it’s sort of all spare time at the moment. Which is a challenge. I used to have no spare time. I worked one or two full-time jobs for over a decade, and I just quit my most recent job a few months ago. This is the first time in my life I’ve been self-employed or under my own direction. So I’m not necessarily supposed to have any more spare time than I used to, because I quit my reliable-income job to be a writer. But I haven’t figured out exactly how one generates an income as such, yet. And beyond the money factor I have a hard time tying my mind down long enough to make it produce anything (every time I was working on this interview, for example, I’d inevitably be distracted by whatever, and I’d click ‘like’ on a picture of a baby alpaca or something, and then I’d think “Shit! I hope the Nat. Brut folks didn’t notice I just did that, since I haven’t sent them my interview yet!”).

I have seven pets so a lot of my time is spent on animal husbandry. I manage lots of forms of poop and fur. I’m a neophyte gardener, and I’d weed through every bit of spare time I have if I could. I actually love weeding. It’s meditative and the results are immediate. I’ve found I’m into flowers more than vegetables. It feels so good on my eyes to sit outside and look at my flowers. And I read, though not as much as I’d like to. I stalk real estate, which is a weird compulsion I’m writing an essay about. We have no savings and absolutely no ability to buy a house in the near future, if ever, but I obsessively refresh Zillow and Estately and Trulia and Redfin, looking at the new houses on the market in this or that neighborhood. And we have three teenagers, so a lot of our spare time is spent going to games or performances or hanging out with them and marveling at how cool they are.

MT: Not to sound like the landed gentry or anything, but it’s sort of all spare time at the moment. Which is a challenge. I used to have no spare time. I worked one or two full-time jobs for over a decade, and I just quit my most recent job a few months ago. This is the first time in my life I’ve been self-employed or under my own direction. So I’m not necessarily supposed to have any more spare time than I used to, because I quit my reliable-income job to be a writer. But I haven’t figured out exactly how one generates an income as such, yet. And beyond the money factor I have a hard time tying my mind down long enough to make it produce anything (every time I was working on this interview, for example, I’d inevitably be distracted by whatever, and I’d click ‘like’ on a picture of a baby alpaca or something, and then I’d think “Shit! I hope the Nat. Brut folks didn’t notice I just did that, since I haven’t sent them my interview yet!”).

I have seven pets so a lot of my time is spent on animal husbandry. I manage lots of forms of poop and fur. I’m a neophyte gardener, and I’d weed through every bit of spare time I have if I could. I actually love weeding. It’s meditative and the results are immediate. I’ve found I’m into flowers more than vegetables. It feels so good on my eyes to sit outside and look at my flowers. And I read, though not as much as I’d like to. I stalk real estate, which is a weird compulsion I’m writing an essay about. We have no savings and absolutely no ability to buy a house in the near future, if ever, but I obsessively refresh Zillow and Estately and Trulia and Redfin, looking at the new houses on the market in this or that neighborhood. And we have three teenagers, so a lot of our spare time is spent going to games or performances or hanging out with them and marveling at how cool they are.

Can you reflect a bit on your dynamic with your parents, and how they’ve influenced you?

We are a reserved clan. I was allowed to be a loner as a kid, for which I’m grateful. My mom was a librarian, which is poetic now that I’m a writer and not a waitress. She kept me in books, boxes and boxes of books for my birthday and any other holiday. I was raised with the so-obvious-it-needed-no-mention idea that writers are people worthy of special respect.

My dad is a musician. He was a high school band director for twenty-five years, and he was also the music minister at most of the churches we attended. So I was raised with the music of wind symphonies and hymns, both of which strongly favor melody. I hear it in my writing now—I write by ear, to make the sentence sound the way it should sound. That internalized rhythm comes from music by way of my dad.

We are a reserved clan. I was allowed to be a loner as a kid, for which I’m grateful. My mom was a librarian, which is poetic now that I’m a writer and not a waitress. She kept me in books, boxes and boxes of books for my birthday and any other holiday. I was raised with the so-obvious-it-needed-no-mention idea that writers are people worthy of special respect.

My dad is a musician. He was a high school band director for twenty-five years, and he was also the music minister at most of the churches we attended. So I was raised with the music of wind symphonies and hymns, both of which strongly favor melody. I hear it in my writing now—I write by ear, to make the sentence sound the way it should sound. That internalized rhythm comes from music by way of my dad.

|

He is also a great storyteller, and I think my approach to short stories thus far comes straight from his style: start with the atmosphere, what it’s like there, wherever there is in this story, building the road; then move backward, setting out cones of relevant backstory; then shift gears and drive the story forward through the established course, revealing why you built the road like that and why you put the cones where you put them. I do it without thinking, because that’s how I heard stories told.

|

Weeding, credit: Evan Stone, 2013

Weeding, credit: Evan Stone, 2013

To what extent did religion play a role in your early life? What is your relationship to religion now?

It was everything. Now it’s nothing, and that is my gift to myself every day. For evangelical righteousness to work you have to have a bedrock conception of yourself as fucked. Otherwise you don’t need saving. When I walked away from the practice of religion I let myself just be a person. A bipedal mammal with no god to serve or disappoint. Just a being with an unknown, unnumbered store of days ahead before it’s over, before I’ve found all the beauty I’ll ever find, which is the closest thing to a spiritual pursuit I need. Show me something beautiful, play me something beautiful, that’s why I’m here. No purpose and no reason beyond that. Just a human animal with kids to raise and stories to tell.

It was everything. Now it’s nothing, and that is my gift to myself every day. For evangelical righteousness to work you have to have a bedrock conception of yourself as fucked. Otherwise you don’t need saving. When I walked away from the practice of religion I let myself just be a person. A bipedal mammal with no god to serve or disappoint. Just a being with an unknown, unnumbered store of days ahead before it’s over, before I’ve found all the beauty I’ll ever find, which is the closest thing to a spiritual pursuit I need. Show me something beautiful, play me something beautiful, that’s why I’m here. No purpose and no reason beyond that. Just a human animal with kids to raise and stories to tell.

Merritt Tierce is the author of the novel Love Me Back (Doubleday).