INTERVIEW | ISSUE SIX

Bum In Suit Mistaken

For Important Man

♦

An interview with JAYSON MUSSON | By KAYLA E. | Fall 2015

Photo by Jonathan Gardenhire

I first discovered Jayson Musson through his Youtube character, Hennessy Youngman, when I was a Visual and Environmental Studies major at Harvard. I’ve been keeping up with his evolving practice ever since, and am continuously impressed by his ability to eloquently (and hilariously) dismantle the pretensions of the art world. I recently had a chance to correspond with Jayson over email, during which I gained some insight into his life and work.

-Kayla E.

|

KE: Can you tell me a bit about what your childhood was like? Where did you grow up?

JM: I grew up in Spring Valley, New York, a town about 25 minutes outside of NYC. After 15 years or so of living in the Bronx (where I was born), my parents settled on Spring Valley as a nice place to pursue the American dream and raise a family. Not too far from the city, but just far enough to give the sense that my parents - two Jamaican immigrants who had worked their asses off - had accomplished something significant. My family was one of the first black families to move into our neighborhood, and subsequently I watched as our white neighbors quickly vacated their homes for whiter pastures while more black families moved in until Spring Valley became what it is today; a suburb of Caribbean and South American families. After a few years in the suburbs, my parents divorced and my dad high-tailed it back into the city to do single guy stuff while my mom was left to raise 3 sons on her own. I was pretty much a very quiet kid; I liked to draw and read comics, and watch cartoons and rap videos after school. I didn’t care too much for athletics or whatever, just drawing. |

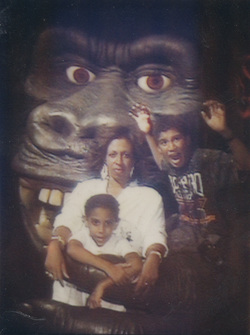

Universal Studios vacation (Jayson on the right)

Universal Studios vacation (Jayson on the right)

KE: I’d love to know more about your family, specifically your mother. How has she influenced you?

JM: I think the greatest contribution to my art via my family is mother’s strength. As a kid I never understood the hardships she faced as a single parent, or as a woman of color working in corporate America, and the innate obstacles she had to deal with in her career. Like most people’s mothers, she can get under my skin in a heartbeat, but she is an incredibly strong woman and her stubbornness is something I look to frequently. I’m stubborn as fuck.

KE: That’s a really helpful quality to have, especially as an artist. Can you tell me about your earliest experiences with art, and how they influenced you?

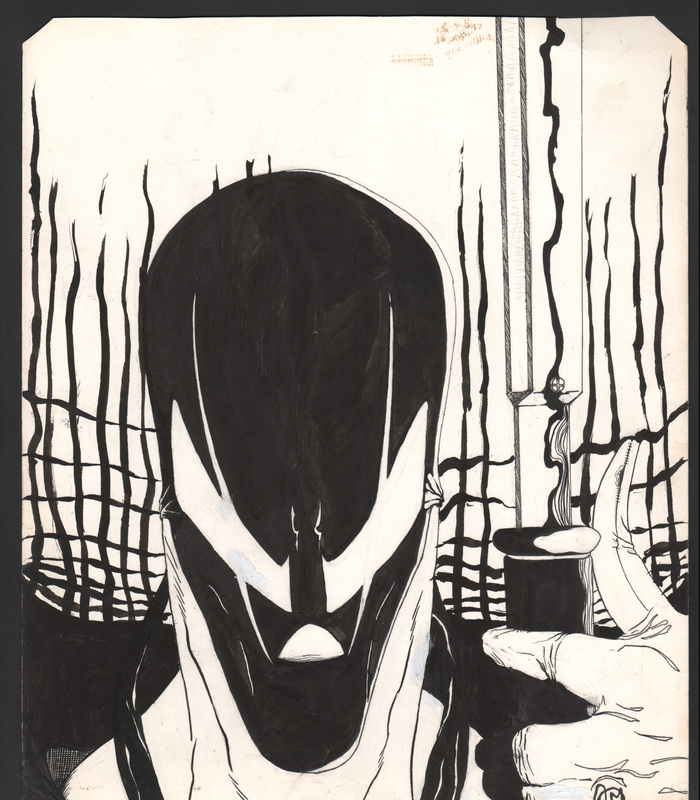

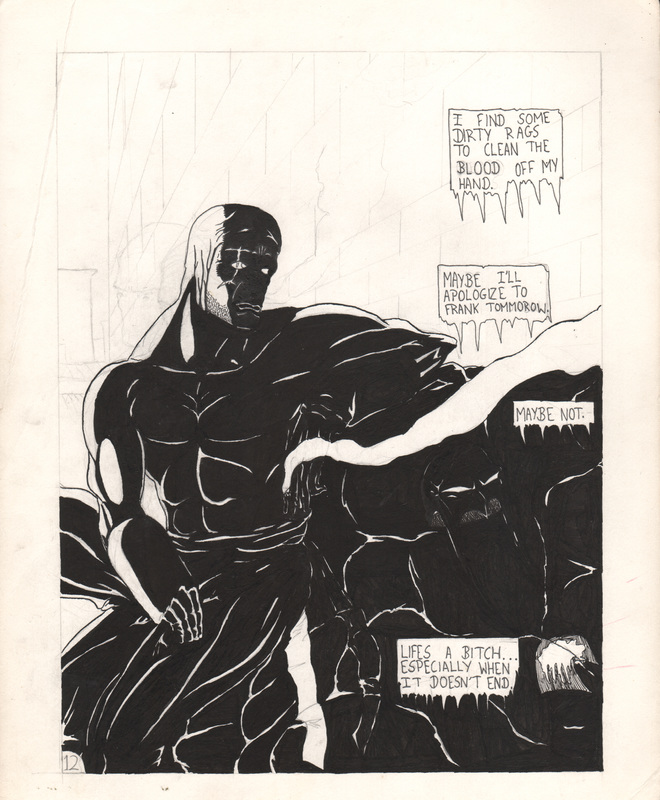

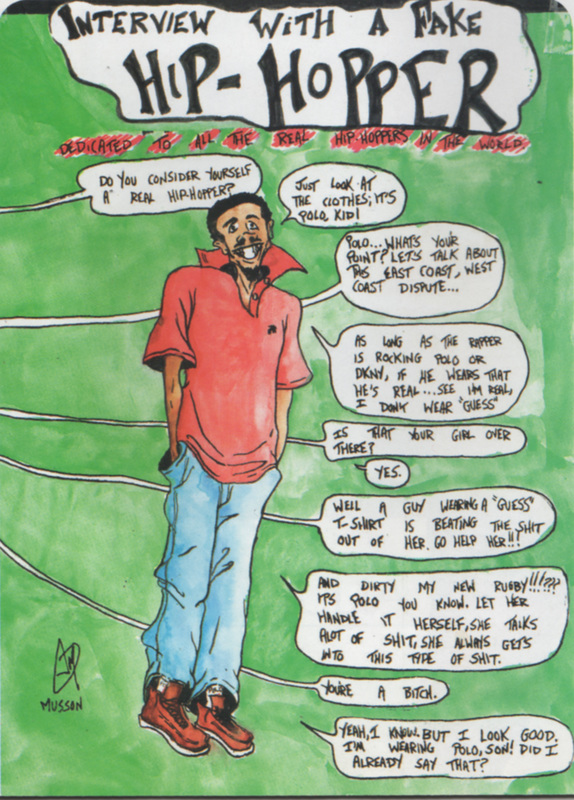

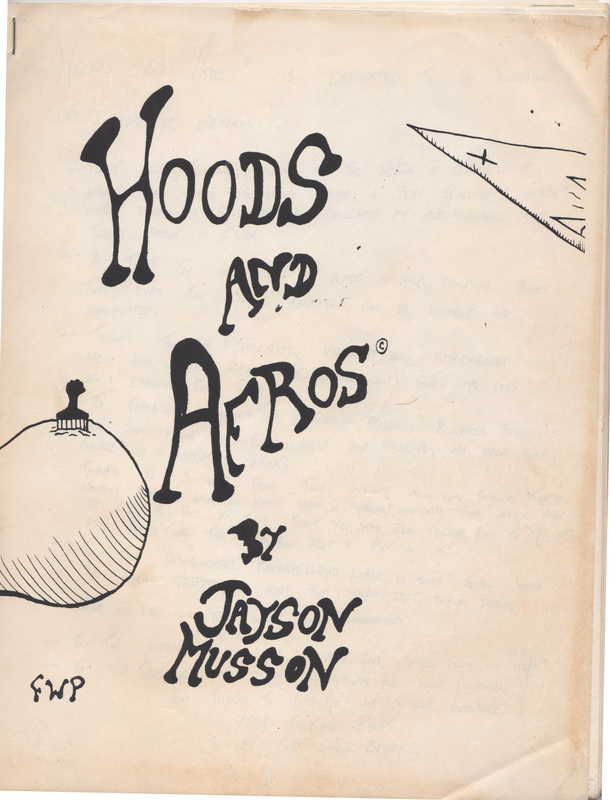

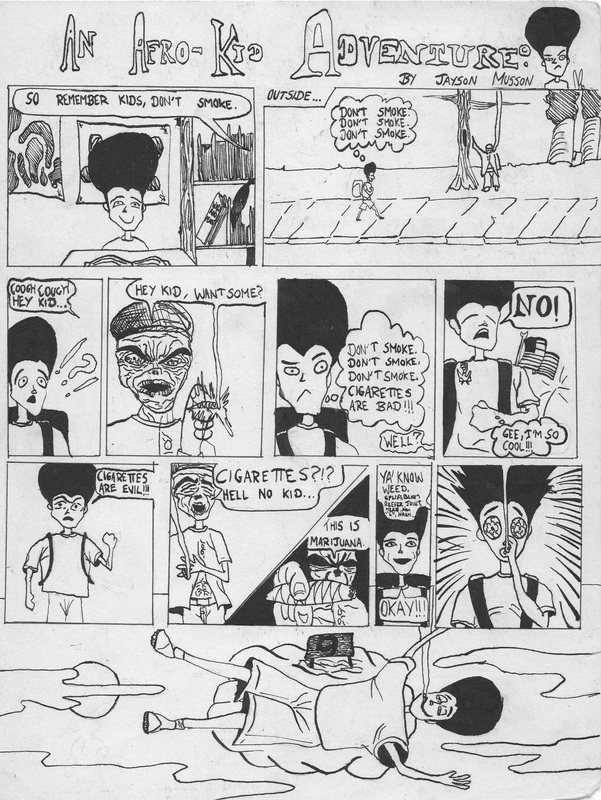

JM: I never went to an art museum proper until I was in college. So my earliest experiences with visual communication that wasn’t television was probably comic books. It was actually this book How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way, which my older brother had lying around the house. It was what the title said it was, a manual for drawing and telling stories through comics in the supposedly dynamic Marvel Comics way. I must’ve gotten a hold of it at a young age because instead of trying the exercises in the book I would color them in, or try to draw images from the book on the very pages of the book itself. In any event, that’s what led me to drawing and to writing, which led to so much more.

JM: I think the greatest contribution to my art via my family is mother’s strength. As a kid I never understood the hardships she faced as a single parent, or as a woman of color working in corporate America, and the innate obstacles she had to deal with in her career. Like most people’s mothers, she can get under my skin in a heartbeat, but she is an incredibly strong woman and her stubbornness is something I look to frequently. I’m stubborn as fuck.

KE: That’s a really helpful quality to have, especially as an artist. Can you tell me about your earliest experiences with art, and how they influenced you?

JM: I never went to an art museum proper until I was in college. So my earliest experiences with visual communication that wasn’t television was probably comic books. It was actually this book How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way, which my older brother had lying around the house. It was what the title said it was, a manual for drawing and telling stories through comics in the supposedly dynamic Marvel Comics way. I must’ve gotten a hold of it at a young age because instead of trying the exercises in the book I would color them in, or try to draw images from the book on the very pages of the book itself. In any event, that’s what led me to drawing and to writing, which led to so much more.

KE: What sort of work do you respond to currently?

JM: It’s funny thinking about visual art I respond to now. To be honest, visual art doesn’t resonate that much with me. There are artists I definitely love - James Ulmer, Devin Troy Strother, Charline von Heyl, Austin Lee, Laura Owens, Mike Smith - but looking at art doesn’t compel me to make art. I respond more to music, comedy, and television than to art objects and performance. It’s just how I am and have been. Seeing Louis CK live was more impactful for me than seeing the Whitney Biennial.

JM: It’s funny thinking about visual art I respond to now. To be honest, visual art doesn’t resonate that much with me. There are artists I definitely love - James Ulmer, Devin Troy Strother, Charline von Heyl, Austin Lee, Laura Owens, Mike Smith - but looking at art doesn’t compel me to make art. I respond more to music, comedy, and television than to art objects and performance. It’s just how I am and have been. Seeing Louis CK live was more impactful for me than seeing the Whitney Biennial.

|

KE: Speaking of which, you’ve suggested that humor plays a substantial role in all of your work. Can you talk a bit about why humor is so important to your practice?

JM: I’ve always worked with humor in my work, and it’s funny to attempt to articulate why, because it’s not something I think about consciously or make an effort to do. It’s just how I process the world; it’s my first language. I guess I’m drawn to humor and comedy because comedy is actually very direct. It takes an incongruency in the world and attempts to move toward the truth of the matter, whereas fine/contemporary art attempts to encourage different ways of perceiving a matter, and doesn’t always try to move toward a truth. Art doesn’t have to do anything it doesn’t want to actually, but comedy does not have that luxury. Comedy has an immediate function to perform. Now this is not to say that art doesn’t move toward truth. Much art does, but art is on a different schedule than comedy. Comedy has to resonate with its audience with very little time to do so, and I’m drawn to that immediacy. Comedy, like art, is highly subjective, but with comedy you don’t need an industry of art pundits, critics, and academics to determine if your response to comedy is on the right side of history or some shit. You intake and you laugh. Hopefully. This was why the Hennessy Youngman project was as successful as it was; it was funny. I’ve heard many folks talk about how ‘smart’ it was, but there is a lot of smart shit out there in that art world. It was the humor of ART THOUGHTZ that brought the non-art audience into the work. |

|

KE: To what extent does your audience’s response to your work matter to you?

JM: Working with humor, I want the humor in the work to actually function. It’s not an oblique process to me. I would like an audience to see the humor in it, or at least be annoyed with me. Haha, I’ll take both. But like I said earlier, I’m pretty stubborn, so if a work isn’t successful, I won’t change it based on audience perception or feedback. Just gotta do me ultimately. KE: How does your family respond to your work? JM: It varies. I’m not sure if they “get” it, but I think they’re pleased that I’m able to make my art, pay my bills, and that I don’t ask to borrow money. KE: I can totally relate to that dynamic. How would you describe your personal trajectory as an artist? JM: Haha, I won’t really have a full answer to this question until I’m dead. But! If I had to put my trajectory in the form of a headline it would be “BUM IN SUIT MISTAKEN FOR IMPORTANT MAN” |

|

KE: Haha! That headline reminds me of some of your earlier text-based work from the Too Black for B.E.T. anthology, which I was lucky enough to find in a used bookstore in Dallas earlier this year. I noticed that you used a persona called PackofRats in that body of work. Can you talk a bit about the function of persona within your artistic practice?

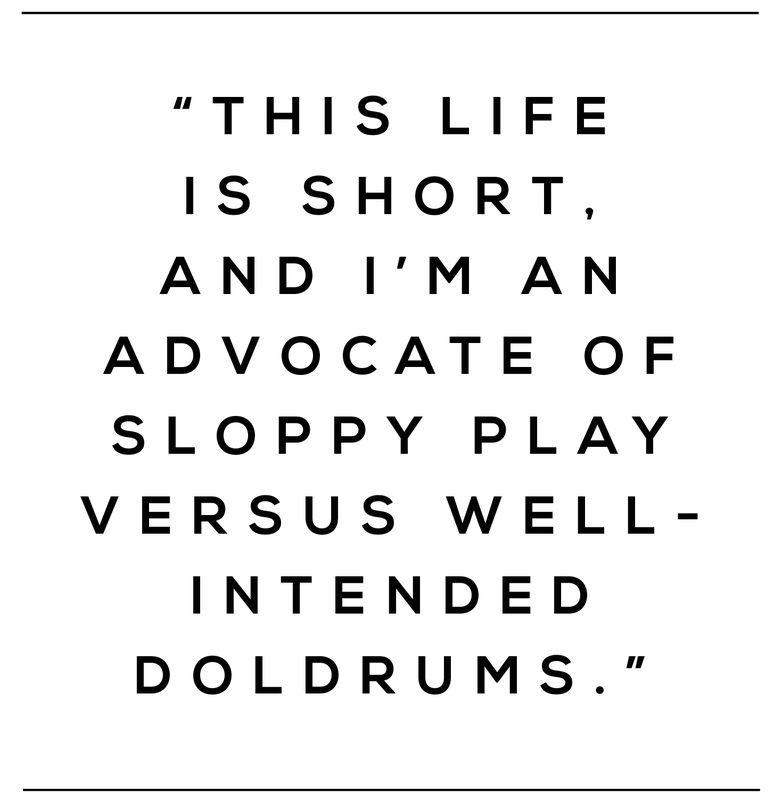

JM: Lol, PackofRats is also my rap name. I think it’s fairly liberating to adopt personas for projects or simply for play. I said in the ART THOUGHTZ video “Beuys-Z” that people are essentially quite boring, and a persona allows you to play outside the confines of your social station or cripplingly boring personality; to ascend past the data that has composed your upbringing and world view and become another, if only for a short time. Of course, the notion that you can become someone else and step outside of your worldview is an innately problematic idea, as your worldview would determine how you would perform being another. But you know what? Who gives a fuck. This life is short, and I’m an advocate of sloppy play versus well-intended doldrums. KE: I also noticed that the rat image that appears in your PackofRats work re-appears in your new online show, The Adventures of Jamel. This makes me wonder - despite the wide range of media you use in your practice, do you see all of your bodies of work as being directly connected in some way? JM: That rat logo is the PackofRats signature. Placing it at the end of The Adventures of Jamel is simply my signature on this massive collaborative project as writer and producer. It’s a way to connect what I’m doing today to what I did in my youth. PackofRats is the creative umbrella it all exists under. It’s the overarching sentiment that carries through all my work, no matter the platform it lives on. today to what I did in my youth. PackofRats is the creative umbrella it all exists under. It’s the overarching sentiment that carries through all my work, no matter the platform it lives on. |

|

KE: What’s your writing process like for projects like Jamel and ART THOUGHTZ?

JM: Hellish. Joking. It changes, honestly. When I was writing ART THOUGHTZ, I would begin a script in text edit. I should say now that ART THOUGHTZ is 100% scripted; my performance was just so bad that it seemed off the cuff. But anyway, I would begin a script, try to cover certain main points in the first draft, and maybe hammer away at 3 other scripts at the same time so when I hit a dead end with one script I could pick up another one and work on that. Then I won’t look at a script for like 3 weeks so I can come back to it with fresh and honest eyes. If I laugh at what I wrote, then I film it. If I look at something I wrote and laugh at it like I’m reading the work of someone else, then I know I did an okay job. The same goes for writing The Adventures of Jamel. I actually write a great deal of those episodes on my phone before I begin hammering out the actual script. I think phone writing is excellent for capturing the broad tonal strokes of the episode, and also for note-taking on the fly. Then I just start writing the actual teleplay out on my computer over the course of months. There are honestly about 10 drafts for each episode with slight and subtle changes. It’s insane and I’m neurotic. |

|

KE: You’ve spoken before about the academic art world being based on a history of ideas that you didn’t feel a part of when you were in art school. Can you talk more about this sentiment? Has this changed for you at all in the years you’ve been a practicing artist?

JM: I got accepted to grad school after being out of school for 8 years or so. During this time in the real world, I did not give one iota of fuck about New York City, or the art world contained therein. I made crazy party rap music with Plastic Little and lived the life of someone living on a pirate ship; party, rap, party rap, art, rinse, repeat. Whatever was going on in the art world, or the history of ideas that it was based upon, meant absolutely nothing to me. I can’t emphasize this enough. I was living in Philadelphia, a place where we generally regard NYC as a tub of over-hyped garbage. And now that I live here, I can confirm that it actually is. Lol. So yeah, I was making drawings and “Too Black for BET,” but that was really outside of the visual trends of the art world. So when I art world. So when I ended up in grad school at University of Pennsylvania on this full scholarship, I was truly a fish out of water. I came face to face with a culture that was completely alien to me. This spawned the Hennessy Youngman project eventually. Now that I’m a practicing artist and have been through the grad school puppy mill, I am much more familiar with the history of art and its component ideas, but I can’t say that it means a great deal to me. |

Nat. Brut Issue Six

Issue Six is our second in print, and features work by Cristina de Middel, Afabwaje Kurian, Chitra Ganesh, Jayson Musson, and more! Issue Six also comes with limited edition supplements: All of Them Witches, a 32-page risograph-printed comic re-interpreting 1950s Harvey Horror comics, plus volume four of our comics section, Early Edition!