Nat. Brut: Do you think with digital photography it has become easier for people to pick up the art? Are there more people trying to be photographers?

Abelardo Morell: Definitely, I mean everybody’s an artist now. It’s kind of cool to have people try it but it’s a little disturbing. You know, it’s like everyone is super cool and super hip.

NB: Has it changed how people emerge into the field of photography?

AM: I think so. Yeah, I think it’s made what I do a little bit stranger. You know how people do a lot of trick photography: take an image and a landscape and photoshop them together—they don’t have to leave their house to make stuff like that. I’m trying to do something that is like photoshop but in a tent in the desert, for real. I think that it’s important that you work really hard to make something magical and not just ‘whatever’, you know. Which is a lot of the attitude: “yeah, I’ve done that.” I’m not putting your generation down, it’s just that there’s so much technology, people get bored with it quickly. I was never bored with photography. I need to find ways to make it new.

NB: Have you converted entirely to digital?

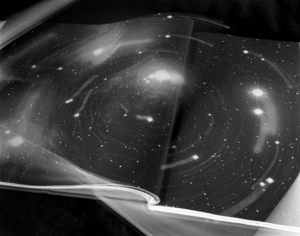

AM: I have, I bought a digital camera a couple of years ago. I waited until it looked really good—the resolution wasn’t good ten years ago, it was just awful. Things looked pixilated, it just didn’t look like a photographic print. One of the nice things about the digital back is that my [camera obscura] exposures were up to five hours, eight hours sometimes; there’s something called reciprocity in film, it’s slow to get the information. Instead of five hours now, my exposures are two to three hours long. Pretty amazingly fast. I do shoot out of fairly low ISO. But the nice thing about the shortness—I mean obviously its nice not to hang around for five hours inside a tent in the desert or something—is now I can do specific times. So if there’s a really interesting shadow on the side of a mountain I actually can get that. Its great, it’s very specific light, it feels more painterly.

NB: Are there things that film photography is better for?

AM: One thing that I still use film for is for photograms. It’s a picture you can make without a camera with objects over a photographic piece of paper. So if you put your hand over a photographic piece of paper in a dark room and shine light over it, you get black and a white hand—that’s the simplest one.

I’m also doing something called cliché vers: I take glass, I put ink on it and as it dries I impress things like leaves or other stuff so you kind of so are creating sort of a hand made thing. I light it, I take that glass and I scan it, and it becomes a digital image.

With photograms what I’m doing is taking eight by ten film, spraying water on it in a dark room, and with a flashlight just kind of light the sides of it. And it’s amazing what happens to it—the water takes on a really beautiful form. Then I develop that in the dark room, just like regular film, and then I scan that too. So the output is all digital, even when it starts as film.

Anyway, I’m not sentimental about the past.

NB: So there’s no nostalgia?

AM: No, there’s people in lectures when I say I’m switched to digital, there’re like, “what about the old fashioned film!?” And I say sometimes—[my wife] tells me to shut up—but I say, “fuck that!” Your generation misses it because you never had too much time to do it, so I can see why the young people get very upset. Because it’s a certain purity. And I think you miss the handmade thing, but I did it for thirty years so, you know, I’m over it. I’m ready to adapt to a new thing.

NB: You have spoken about your photography as a viewpoint in which you find life in mundane things. Is photography the tool by which you get there, or do you see the world in that way and use photography as tool to translate it?

AM: I think if I didn’t have photography, I probably wouldn’t see the world the way I look at it. So it’s always tied up with photography, or art. If I see something interesting it’s always I need to make a picture of that. It’s nice to just say “wow, great” but to me it’s unsatisfying just to go “wow”. I need to make a picture to almost let people know what’s possible.

I made a picture of a pencil. And it just happened. I always tell this story, I think I was close to fifty years old when I saw that shadow. And I often think, “I’ve never seen that! I’m fifty years old and I’ve never seen that!” but of course it’s happening all the time. Which, I don’t know, no time for I guess, always texting somebody? [laughs] Paying our mortgages? I don’t know. So it’s interesting to sort of use art to get that feeling. That’s why I’m an artist; because I need a medium by which to get to it. The way a writer would.

NB: Do you ever have that feeling and then take the picture and find it uninteresting in the end?

AM: Yeah, that happens a lot. The thought and the thing, eh, bad marriage. But the more I do it the closer it gets. Because I’m thinking now in a way tied up with photography. So if I think it, it’s linked to a certain way of envisioning things. It works out more and more. More than when I was young. When I was your age I was like “Ugh, yes! Unicorns coming in!” [laughs].

NB: How did you get your start? You went to Bowdoin? It seems as though having someone take you under their wing or having someone believe in you is important in fostering an artistic career.

AM: And I had that. I had a teacher, and I was studying engineering and I did really badly at it—flunked physics and math. I think sophomore year I took a photography course and it was a wonderful teacher. He really took me in. I took two or three rolls and was kind of like “I can do something”. And I was good at it; I mean, I think I was pretty good at it.

NB: Did he sort of pick you out?

AM: Yeah, we became friends and he really helped me out. I mean, he became like a second father to me. He’s fantastic, we’re still very close friends.

NB: Does he do his own photography?

AM: He did and he quit a while ago and I was sort of disappointed by that because I can never think about quitting. But he was fantastic. He also wouldn’t get in the way too much if I did really stupid stuff sometimes. He wouldn’t say “stupid,” he was just like “interesting decision.” He knew how far to let me stumble.

He also intellectually was helpful, he knew about music a lot like Bach...you know, people like that. So I learned a lot about the visual arts, music, Zen, poetry. So it was really enriching, it wasn’t just F stops. It was about the sensibility of being an artist.

NB: What do you think the relationship is between the artist and the art critic? How do you feel about criticism written about your own work?

AM: It’s complicated. The good critics are rare because they can take something apart without killing it. Critics after they’re done with you it’s like a skeleton, you’re dead, you know? There are very few critics who I actually admire but I think you need them to let other people understand what some of the more difficult work might be about: to link it to common knowledge, a bridge. There’s a great line about it: ‘art criticism is to artists what Ornithology is to birds’. I just love that. Because you know, in some way birds are, “yeah Ornithology, great! I fly.” In a way it’s sort of related, but not at all.

NB: Do you think an artist makes a better critic?

AM: I think it helps if you do the thing that you’re critiquing. I miss that, I miss people who are imbued with that sense of what people make. I think a lot of criticism now is so abstract and doesn’t take the hand into account. And I think a lot of it is kind of bullshit, it’s all theoretical.

I’ve been in critiques at MassArt when we’ve invited critics. There was this one time when a student of mine put some work up on the wall, and this guy was sitting sort of far away from the wall and said something like, “I suppose I should look at the work.” He was ready to, from far away, look at stuff and have ideas already. Its like, what? The disconnect between the object and the thought, I think that’s really awful, and there’s a trend to do that now.

NB: You think more so than before?

AM: I think so. Although in the eighties there was Postmodernism and there was so much bullshit written during that time. People were saying, “Photography’s dead. What’s the point?” [laughs]. But it was like really terrible. I think artists are doing more about trusting their process now. But, it depends on the critic. Like Julia Margaret Cameron, one of the first women photographers. She was like forty years old and someone gave her a camera as a gift. She made some of the most beautiful portraits; great, great portraits. But often times she’d take them really close to people and the depth of field is low. So the eyes are sharp and nothing else, and I’ve read critics who talk about how Margaret intentionally made that happen. And it’s like no, that’s what happens when you get close: if you focus on the eyes nothing else will be sharp. That’s the camera, that’s the lens, baby. It’s not like a painter, “Oh I’m going to make that out of focus”. No, that’s what comes with the craft. It’s like if you don’t understand that you’re kind of uninformed. So, you have to know the craft.

NB: Have you read criticism about your work and gotten frustrated or feel like it’s off the mark?

AM: No, that’s interesting. Well sometimes I think people want to link my Cuban heritage to my work. It’s important. My life did change dramatically and it was a big deal. But it’s not always important, maybe obliquely so, but it’s not like I want to make work that is just that. So sometimes people misunderstand that, they think the Cuban me is trying to get out or something.

I gave a talk in Houston a long time ago and some woman, American woman, asked me—she meant well but she said, “your work doesn’t look like the work of a Cuban?” It’s really important not to feel yourself as part of a ghetto. Like if you’re Dutch you’re cold and you think in squares. [laughs]. If you’re Cuban you’ve got your maracas! Cha cha cha! So I said, “I came to this country to be free…a Cuban can do anything. I’m interested in light bulbs!” Sometimes people do feel like they need to put you in a ghetto, a package, of what you are and I always rebel against that. Not that I’m counter to it but I’m free to whatever—photograph a pencil!

NB: How did you feel about, for example, that Charles Simic paper written about your work?

AM: I think that he’s right on. His poetry and his writing are so much about the mystery of things, the surreal nature of life. In fact there’s a book of his poems where one of my pictures is the cover, the paper bag [The Voice at 3:00 A.M.: Selected Late and New Poems]. Which is perfect, you know, the idea of a regular thing, not some bizarre object but a paper bag, having a darkness to it. Like you’re entering hell, you know? But it’s just a paper bag. I really like that sensibility; it’s not the gates of Hell, it’s just a paper bag. It has that weird double-edgedness to it. One of the great Haikuists, Issa, wrote a really nice haiku like this:

In this world

we walk on the roof of hell

gazing at flowers

I mean, two realities like that just thinly divided, great.

NB: And you’re still a professor at Mass Art?

AM: I retired two years ago after twenty-seven years. I still teach a Graduate class once a week in the fall. I still want to be in touch with young people. I loved it, it was the best thing I ever did but it was time to get work done, I’ve got a big retrospective coming up, it’s like 110 pictures: the Art Institute of Chicago, The Getty in Los Angeles, High Museum in Atlanta. It’s a big show—huge. And I wanted to make new pictures before I croak. So I’m working more than ever. But teaching, loved it.

NB: What have you learned from being on the other end of the mentor relationship?

AM: Number one, if you teach you sort of have to be clear about what you’re saying. You can’t just say “Oh yeah, whatever.” You can’t be like the students! It makes you try to be clearer with your information. I think that clarity translates into your own way of making work, so it helped me a lot.

I also think being with young people is a good idea no matter what, just the energy, the strangeness...I learned a lot form my students, it’s a two-way street. I loved seeing someone get it from one week to another, to see them look at a print and light up, it’s the best feeling. I have lots of students who I still see and send me stuff when they have shows. I miss it but not that much, which is great.

NB: Have you had periods where you’ve had a writers’ block equivalent?

AM: Not for a long time. I’ve had that. Not for a while [knocks on wood], I’ve got lots of ideas. Seems like everyday I just come up with new ideas. And some things are like—the camera obscura work led to the tent thing, which is nice because it’s kind of like the same idea…cliché vers came from early photograms and I’m trying to do Books in color now. So, no, I’m lucky to welcome these things.

NB: Tell me about doing Alice in Wonderland.

AM: Someone thought it would be interesting if I decided to do Alice, which I liked, but I also wanted to do it my own way. So that Alice’s travels would be in the territory of books. In fact I’m thinking about illustrating the next one,Through The Looking Glass. So that both of them could be published together, but I’m struggling trying to come up with something a little bit different from the first one. It’s Lewis Carroll’s 150th anniversary coming up, so…I might do it.

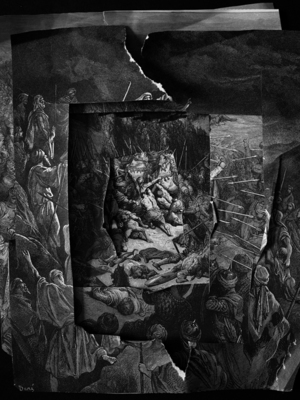

NB: How do you go about pairing images to someone else’s words or narrative?

AM: Well in the case of Lewis Carroll it’s easy because they were illustrated originally by a guy named Tenniel. The images are there so it’s like, how do I make that same image? Not rip it off totally but do something to it. So what I did was have cut-outs of the original—in fact I still have a box with Alice heads and stuff—and it’s very low tech, you know cardboard with a stick holding Alice. But the books and the shadows felt like it contributed some thing new.Through the Looking Glass has a lot of chess because she is moving in a Chess pattern, it’s got a lot of mirrors, and frames. So I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about the idea of mirrors and how to make that the structure of my pictures. And it’s a very mysterious thing, it’s almost like you need a skeleton first to hold the thing conceptually, but how do you make the pictures so that it doesn’t feel like they’re stiff?

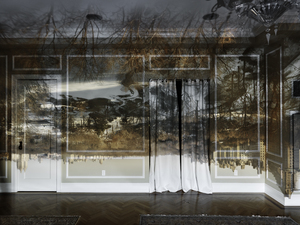

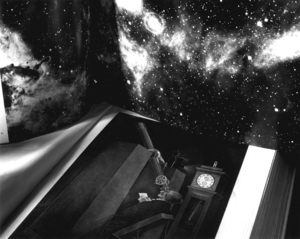

NB: The camera obscura work often distorts the scale of certain objects or images, is this particularly interesting to you? What is affective about it? Are those images dialectical?

AM: Yeah, like the room suddenly allowing another landscape in it, naturally. It’s no longer the same room, no longer the same landscape, it’s a new hybrid that is being created: the dirt on the ground suddenly taking on the mountains…the kind of a weird, maybe forced marriages of things. I’m really quite interested in that, how a thing can become something else—and again, naturally. When I made my first camera obscure in ‘91—the camera obscura has been done for a long time—but no one had made a picture like that in ‘91, no one had photographed the effect itself. People talked about Vermeer using it but no one had photographed the effect and I thought, in a way, I had invented photography, but it’s been here all along. Yeah, I want to make the world new in a way, and not quite destroy it but make it kind of a new weird world. Like a dialectic. I like that aspect of the Hegelian dialectic—the synthesis.

NB: You have often spoken about how much you love being at home; other then taking many pictures there, what is special about the space of the 'home'?

AM: For me, it’s important because the idea of being loving and being loved is nurturing. You know, it feels like ‘okay, even though I might be kind of crazy there’s somebody who I care about.’ Also, maybe because I come from a working-class background the idea of being a recluse, the guy dressed in black in New York never—I never think of myself as that fancy. I like the idea of growing from the ground up, the base. And my family’s always been there for me, there’s no separation. My photography changed when [my son] was born because I allowed emotions to enter me, but to the creative side too. To have emotional meat to the inventions, for me, that’s always really important. There’shuman creativity going on.

Abelardo Morell is a world-renowned photographer best for his work with camera obscura. He has received numerous honors including a Guggenheim Fellowship and International Center for Photography Infinity Award. The author of seven books, Morell's work has been displayed in galleries and museums across the globe.

< Previous

Next >

Abelardo Morell: Definitely, I mean everybody’s an artist now. It’s kind of cool to have people try it but it’s a little disturbing. You know, it’s like everyone is super cool and super hip.

NB: Has it changed how people emerge into the field of photography?

AM: I think so. Yeah, I think it’s made what I do a little bit stranger. You know how people do a lot of trick photography: take an image and a landscape and photoshop them together—they don’t have to leave their house to make stuff like that. I’m trying to do something that is like photoshop but in a tent in the desert, for real. I think that it’s important that you work really hard to make something magical and not just ‘whatever’, you know. Which is a lot of the attitude: “yeah, I’ve done that.” I’m not putting your generation down, it’s just that there’s so much technology, people get bored with it quickly. I was never bored with photography. I need to find ways to make it new.

NB: Have you converted entirely to digital?

AM: I have, I bought a digital camera a couple of years ago. I waited until it looked really good—the resolution wasn’t good ten years ago, it was just awful. Things looked pixilated, it just didn’t look like a photographic print. One of the nice things about the digital back is that my [camera obscura] exposures were up to five hours, eight hours sometimes; there’s something called reciprocity in film, it’s slow to get the information. Instead of five hours now, my exposures are two to three hours long. Pretty amazingly fast. I do shoot out of fairly low ISO. But the nice thing about the shortness—I mean obviously its nice not to hang around for five hours inside a tent in the desert or something—is now I can do specific times. So if there’s a really interesting shadow on the side of a mountain I actually can get that. Its great, it’s very specific light, it feels more painterly.

NB: Are there things that film photography is better for?

AM: One thing that I still use film for is for photograms. It’s a picture you can make without a camera with objects over a photographic piece of paper. So if you put your hand over a photographic piece of paper in a dark room and shine light over it, you get black and a white hand—that’s the simplest one.

I’m also doing something called cliché vers: I take glass, I put ink on it and as it dries I impress things like leaves or other stuff so you kind of so are creating sort of a hand made thing. I light it, I take that glass and I scan it, and it becomes a digital image.

With photograms what I’m doing is taking eight by ten film, spraying water on it in a dark room, and with a flashlight just kind of light the sides of it. And it’s amazing what happens to it—the water takes on a really beautiful form. Then I develop that in the dark room, just like regular film, and then I scan that too. So the output is all digital, even when it starts as film.

Anyway, I’m not sentimental about the past.

NB: So there’s no nostalgia?

AM: No, there’s people in lectures when I say I’m switched to digital, there’re like, “what about the old fashioned film!?” And I say sometimes—[my wife] tells me to shut up—but I say, “fuck that!” Your generation misses it because you never had too much time to do it, so I can see why the young people get very upset. Because it’s a certain purity. And I think you miss the handmade thing, but I did it for thirty years so, you know, I’m over it. I’m ready to adapt to a new thing.

NB: You have spoken about your photography as a viewpoint in which you find life in mundane things. Is photography the tool by which you get there, or do you see the world in that way and use photography as tool to translate it?

AM: I think if I didn’t have photography, I probably wouldn’t see the world the way I look at it. So it’s always tied up with photography, or art. If I see something interesting it’s always I need to make a picture of that. It’s nice to just say “wow, great” but to me it’s unsatisfying just to go “wow”. I need to make a picture to almost let people know what’s possible.

I made a picture of a pencil. And it just happened. I always tell this story, I think I was close to fifty years old when I saw that shadow. And I often think, “I’ve never seen that! I’m fifty years old and I’ve never seen that!” but of course it’s happening all the time. Which, I don’t know, no time for I guess, always texting somebody? [laughs] Paying our mortgages? I don’t know. So it’s interesting to sort of use art to get that feeling. That’s why I’m an artist; because I need a medium by which to get to it. The way a writer would.

NB: Do you ever have that feeling and then take the picture and find it uninteresting in the end?

AM: Yeah, that happens a lot. The thought and the thing, eh, bad marriage. But the more I do it the closer it gets. Because I’m thinking now in a way tied up with photography. So if I think it, it’s linked to a certain way of envisioning things. It works out more and more. More than when I was young. When I was your age I was like “Ugh, yes! Unicorns coming in!” [laughs].

NB: How did you get your start? You went to Bowdoin? It seems as though having someone take you under their wing or having someone believe in you is important in fostering an artistic career.

AM: And I had that. I had a teacher, and I was studying engineering and I did really badly at it—flunked physics and math. I think sophomore year I took a photography course and it was a wonderful teacher. He really took me in. I took two or three rolls and was kind of like “I can do something”. And I was good at it; I mean, I think I was pretty good at it.

NB: Did he sort of pick you out?

AM: Yeah, we became friends and he really helped me out. I mean, he became like a second father to me. He’s fantastic, we’re still very close friends.

NB: Does he do his own photography?

AM: He did and he quit a while ago and I was sort of disappointed by that because I can never think about quitting. But he was fantastic. He also wouldn’t get in the way too much if I did really stupid stuff sometimes. He wouldn’t say “stupid,” he was just like “interesting decision.” He knew how far to let me stumble.

He also intellectually was helpful, he knew about music a lot like Bach...you know, people like that. So I learned a lot about the visual arts, music, Zen, poetry. So it was really enriching, it wasn’t just F stops. It was about the sensibility of being an artist.

NB: What do you think the relationship is between the artist and the art critic? How do you feel about criticism written about your own work?

AM: It’s complicated. The good critics are rare because they can take something apart without killing it. Critics after they’re done with you it’s like a skeleton, you’re dead, you know? There are very few critics who I actually admire but I think you need them to let other people understand what some of the more difficult work might be about: to link it to common knowledge, a bridge. There’s a great line about it: ‘art criticism is to artists what Ornithology is to birds’. I just love that. Because you know, in some way birds are, “yeah Ornithology, great! I fly.” In a way it’s sort of related, but not at all.

NB: Do you think an artist makes a better critic?

AM: I think it helps if you do the thing that you’re critiquing. I miss that, I miss people who are imbued with that sense of what people make. I think a lot of criticism now is so abstract and doesn’t take the hand into account. And I think a lot of it is kind of bullshit, it’s all theoretical.

I’ve been in critiques at MassArt when we’ve invited critics. There was this one time when a student of mine put some work up on the wall, and this guy was sitting sort of far away from the wall and said something like, “I suppose I should look at the work.” He was ready to, from far away, look at stuff and have ideas already. Its like, what? The disconnect between the object and the thought, I think that’s really awful, and there’s a trend to do that now.

NB: You think more so than before?

AM: I think so. Although in the eighties there was Postmodernism and there was so much bullshit written during that time. People were saying, “Photography’s dead. What’s the point?” [laughs]. But it was like really terrible. I think artists are doing more about trusting their process now. But, it depends on the critic. Like Julia Margaret Cameron, one of the first women photographers. She was like forty years old and someone gave her a camera as a gift. She made some of the most beautiful portraits; great, great portraits. But often times she’d take them really close to people and the depth of field is low. So the eyes are sharp and nothing else, and I’ve read critics who talk about how Margaret intentionally made that happen. And it’s like no, that’s what happens when you get close: if you focus on the eyes nothing else will be sharp. That’s the camera, that’s the lens, baby. It’s not like a painter, “Oh I’m going to make that out of focus”. No, that’s what comes with the craft. It’s like if you don’t understand that you’re kind of uninformed. So, you have to know the craft.

NB: Have you read criticism about your work and gotten frustrated or feel like it’s off the mark?

AM: No, that’s interesting. Well sometimes I think people want to link my Cuban heritage to my work. It’s important. My life did change dramatically and it was a big deal. But it’s not always important, maybe obliquely so, but it’s not like I want to make work that is just that. So sometimes people misunderstand that, they think the Cuban me is trying to get out or something.

I gave a talk in Houston a long time ago and some woman, American woman, asked me—she meant well but she said, “your work doesn’t look like the work of a Cuban?” It’s really important not to feel yourself as part of a ghetto. Like if you’re Dutch you’re cold and you think in squares. [laughs]. If you’re Cuban you’ve got your maracas! Cha cha cha! So I said, “I came to this country to be free…a Cuban can do anything. I’m interested in light bulbs!” Sometimes people do feel like they need to put you in a ghetto, a package, of what you are and I always rebel against that. Not that I’m counter to it but I’m free to whatever—photograph a pencil!

NB: How did you feel about, for example, that Charles Simic paper written about your work?

AM: I think that he’s right on. His poetry and his writing are so much about the mystery of things, the surreal nature of life. In fact there’s a book of his poems where one of my pictures is the cover, the paper bag [The Voice at 3:00 A.M.: Selected Late and New Poems]. Which is perfect, you know, the idea of a regular thing, not some bizarre object but a paper bag, having a darkness to it. Like you’re entering hell, you know? But it’s just a paper bag. I really like that sensibility; it’s not the gates of Hell, it’s just a paper bag. It has that weird double-edgedness to it. One of the great Haikuists, Issa, wrote a really nice haiku like this:

In this world

we walk on the roof of hell

gazing at flowers

I mean, two realities like that just thinly divided, great.

NB: And you’re still a professor at Mass Art?

AM: I retired two years ago after twenty-seven years. I still teach a Graduate class once a week in the fall. I still want to be in touch with young people. I loved it, it was the best thing I ever did but it was time to get work done, I’ve got a big retrospective coming up, it’s like 110 pictures: the Art Institute of Chicago, The Getty in Los Angeles, High Museum in Atlanta. It’s a big show—huge. And I wanted to make new pictures before I croak. So I’m working more than ever. But teaching, loved it.

NB: What have you learned from being on the other end of the mentor relationship?

AM: Number one, if you teach you sort of have to be clear about what you’re saying. You can’t just say “Oh yeah, whatever.” You can’t be like the students! It makes you try to be clearer with your information. I think that clarity translates into your own way of making work, so it helped me a lot.

I also think being with young people is a good idea no matter what, just the energy, the strangeness...I learned a lot form my students, it’s a two-way street. I loved seeing someone get it from one week to another, to see them look at a print and light up, it’s the best feeling. I have lots of students who I still see and send me stuff when they have shows. I miss it but not that much, which is great.

NB: Have you had periods where you’ve had a writers’ block equivalent?

AM: Not for a long time. I’ve had that. Not for a while [knocks on wood], I’ve got lots of ideas. Seems like everyday I just come up with new ideas. And some things are like—the camera obscura work led to the tent thing, which is nice because it’s kind of like the same idea…cliché vers came from early photograms and I’m trying to do Books in color now. So, no, I’m lucky to welcome these things.

NB: Tell me about doing Alice in Wonderland.

AM: Someone thought it would be interesting if I decided to do Alice, which I liked, but I also wanted to do it my own way. So that Alice’s travels would be in the territory of books. In fact I’m thinking about illustrating the next one,Through The Looking Glass. So that both of them could be published together, but I’m struggling trying to come up with something a little bit different from the first one. It’s Lewis Carroll’s 150th anniversary coming up, so…I might do it.

NB: How do you go about pairing images to someone else’s words or narrative?

AM: Well in the case of Lewis Carroll it’s easy because they were illustrated originally by a guy named Tenniel. The images are there so it’s like, how do I make that same image? Not rip it off totally but do something to it. So what I did was have cut-outs of the original—in fact I still have a box with Alice heads and stuff—and it’s very low tech, you know cardboard with a stick holding Alice. But the books and the shadows felt like it contributed some thing new.Through the Looking Glass has a lot of chess because she is moving in a Chess pattern, it’s got a lot of mirrors, and frames. So I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about the idea of mirrors and how to make that the structure of my pictures. And it’s a very mysterious thing, it’s almost like you need a skeleton first to hold the thing conceptually, but how do you make the pictures so that it doesn’t feel like they’re stiff?

NB: The camera obscura work often distorts the scale of certain objects or images, is this particularly interesting to you? What is affective about it? Are those images dialectical?

AM: Yeah, like the room suddenly allowing another landscape in it, naturally. It’s no longer the same room, no longer the same landscape, it’s a new hybrid that is being created: the dirt on the ground suddenly taking on the mountains…the kind of a weird, maybe forced marriages of things. I’m really quite interested in that, how a thing can become something else—and again, naturally. When I made my first camera obscure in ‘91—the camera obscura has been done for a long time—but no one had made a picture like that in ‘91, no one had photographed the effect itself. People talked about Vermeer using it but no one had photographed the effect and I thought, in a way, I had invented photography, but it’s been here all along. Yeah, I want to make the world new in a way, and not quite destroy it but make it kind of a new weird world. Like a dialectic. I like that aspect of the Hegelian dialectic—the synthesis.

NB: You have often spoken about how much you love being at home; other then taking many pictures there, what is special about the space of the 'home'?

AM: For me, it’s important because the idea of being loving and being loved is nurturing. You know, it feels like ‘okay, even though I might be kind of crazy there’s somebody who I care about.’ Also, maybe because I come from a working-class background the idea of being a recluse, the guy dressed in black in New York never—I never think of myself as that fancy. I like the idea of growing from the ground up, the base. And my family’s always been there for me, there’s no separation. My photography changed when [my son] was born because I allowed emotions to enter me, but to the creative side too. To have emotional meat to the inventions, for me, that’s always really important. There’shuman creativity going on.

Abelardo Morell is a world-renowned photographer best for his work with camera obscura. He has received numerous honors including a Guggenheim Fellowship and International Center for Photography Infinity Award. The author of seven books, Morell's work has been displayed in galleries and museums across the globe.

< Previous

Next >