FICTION | ISSUE SIX

Asha

♦

By MORGAN JERKINS | Fall 2015

ca. 1882-1885

Long ago, there was a woman named Asha whose mahogany skin was the only spot present in a village of lily-white residents. She had wide hips, lips so thick and heavy that they always puckered outward, a nose broad enough to invite anyone’s essence inside, and dark, depthless eyes that could absorb anything they perceived. Folks say she didn’t talk much to nobody, always hung her head low, said “please” and “thank you” for any old small thing, and minded her business. She didn’t have any family, and she kept a large cottage next to an open stream all by herself. Even so, everyone in town knew Asha well, and if you asked anyone what she did for a living, they would gush and tell you, “Everything.”

It all began one March afternoon. Asha was making her way into town when she heard shrieks coming from Mayor Donnelson’s home. Without thinking, Asha burst through the front door and sprinted up the steps to find Mayor Donnelson’s wife crying over a large hole in one of her blue lace gowns. Although the woman had a needle and thread sitting right on her vanity chest, she paced across the room, crying and throwing her hands up in the air as if she were out of resources. She was so overcome with sadness that she was not startled when Asha came panting up the steps with her hands balled into fists and her feet spread apart, ready to fight if necessary.

“Are you awright, Missus Donnelson?”

Mayor Donnelson’s wife held up the gown and sputtered indecipherable words that weaseled out through her melodramatic sobs.

“Give it here.”

Asha took the gown in her hands and held the material up to the sunlight permeating the adjacent windows. She fiddled around with some of the loose strings, grabbed the needle, and did a few loopty loops until the dress was as virgin to the touch as when Missus Donnelson first purchased it. Afterwards, Asha bowed her head, waved her hand in front of her chest to eschew any gratitude that the Mayor’s Missus wanted to bestow upon her, and went on her way to run some errands.

Missus Donnelson’s network was vast, so news of Asha’s generosity spread to the other end of the village before the last words of the Mayor’s wife’s account could be uttered. When Asha returned to her house with groceries in hand, there was a group of women at her doorstep waiting with their holey dresses, stretched out shirts, dirty undergarments, and blemished jewelry. Their crestfallen faces communicated enough. Asha sighed, opened her door, and stepped aside for them to make themselves comfortable in her living room. One by one, she stitched up holes, tightened shirts, and removed stains in places that would make you blush. In the meantime, the women busied themselves with conversation.

“Do you plan on going to the gala on Friday evening?”

“Of course I have to go. I have a 10,000-dollar plate. How about you, Betty?”

“Going? I planned the event!”

The women broke out into hearty laughter while Asha sat in the kitchen at the table, coddling their precious gemstones. She never received an invitation to no gala. Maybe they all belonged to a certain club. In any case, she had jobs to do and things to fix. Besides, she liked having them in her house. They regaled her with embellishments of evening soirees and afternoon tea parties, ideas that were as abstract as their gowns, which she could only dream of having the privilege of holding in her hands. The women stayed well into the night and thanked her upon leaving as they crossed the threshold of her front door. It didn’t bother her much. Thank yous were courtesy enough, and their currency filled her with a goodness that replaced the nice meal that she planned to have that evening.

The next afternoon, her visitors quadrupled. Clothes needed ironing, shoes needed shining, and jewelry needed cleaning. Although the work was long and calluses started to grow on her hands and feet, she bore it all in stride, and soon she was able to be a part of their conversations.

“Asha, have you ever thought about watching children since you don’t have any of your own?”

Holding onto a chunky baby or two would break up the monotony of caring for inanimate things. Soon the clothes needed ironing, the shoes needed shining, the jewelry needed cleaning, and the children needed watching. Although everyone, including the kids, loved her, Asha never understood why they entrusted her with these services when there were plenty of others in town who could do the same tasks.

“Oh, you’re just the best, Asha!” one woman gushed as she stretched a hand out towards Asha, not letting her manicured fingers grace Asha’s body.

One evening, after her clientele had flooded out of her house, Asha felt a pulsating throb in both of her eardrums as she stood in the middle of her living room. The silence was deafening, and she stomped around the house, opening and shutting doors to feel like she had company again. Once she tired herself out, she took off her tattered flats and discovered that her soles were bleeding. Pains were shooting down both her legs and her neck was stiff. The next morning, her ailments not only remained, but had intensified. She was so weak that she could not make it to her bedroom, so she sprawled out on the couch, moaning and groaning. Folks from the town began rapping at her door, and she could hear their indistinct voices multiplying.

“Asha! Are you in there?”

“Asha!”

“Asha!”

“Asha! Are you alright in there?”

“I’m not feeling so well, ladies. Not today,” Asha croaked.

“Not today?” All the women repeatedly asked.

“I’m sorry!” Asha called out, her voice cracking at the end. “I will let you know when I’m feeling better. I’m sick.”

“What about our children?”

“What about our clothes?”

“What about our jewelry?”

“I’m so sorry. Another day!”

These ladies treated Asha’s rebuff like words from a foreign tongue, as they had never heard rejection before. Instead of retiring to their homes and going to bed, they told their husbands, who then exchanged and re-exchanged this information with their colleagues.

“Who does she think she is?” was the common sentiment.

Rather than allowing their anger to taper off with the help of a night’s rest, the ladies returned to Asha’s house with their husbands. They didn’t rap on the door, but rather pounded their fists into the cherry oak wood.

“Open the door, Asha! Open the door!”

Asha didn’t have the strength to hide in her bedroom, so she placed a pillow over her head, hoping to block out the noise and disengage herself from reality. Suddenly, glass shattered. Someone knocked out all of her windows and the townspeople started to pour into her home. Two men lifted a screaming Asha from the couch and held her down while others took to her kitchen, throwing plates on the ground and dumping food onto the floors. Asha begged for them to stop, but they continued laughing, whooping, and hollering as they went into her bedroom and smeared her clothes with the mess of food that they had made. They ransacked her cabinets, drawers, nightstands, and closets.

When all was said and done, they quietly left in two single file lines. Asha was left on the ground in her living room, unable to pick herself up, and her cries reverberated throughout her stripped cottage. She spent the night on her hands and knees, trying to clean up what she could, but by morning, her house still carried a musty scent from the men and women who had violated her walls. After painstaking effort, she was able to stand and go back into town to buy things. She kept her head low and refused to make eye contact until Mayor Donnelson approached her.

“Have you learned your lesson?” He asked.

“Yes,” she said in a faint voice.

“Good. Now go back home as soon as you can. My wife and the rest of her friends will be waiting for you.”

“Okay.”

What else was she supposed to say?

Asha returned to tending to clothes and jewelry with calloused and bruised hands, feet, and limbs, and continued eavesdropping on the townswomen’s riveting tales of extravagance. She and her home had become nothing more than freshly carved-out gourds into which everyone could pour their hollow sounds, leaving behind nothing for her own satiation.

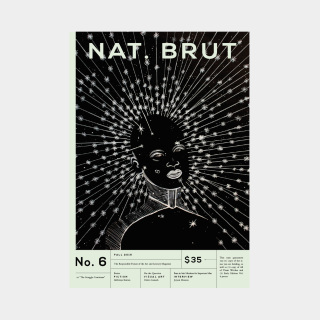

Nat. Brut Issue Six

Issue Six is our second in print, and features work by Cristina de Middel, Afabwaje Kurian, Chitra Ganesh, Jayson Musson, and more! Issue Six also comes with limited edition supplements: All of Them Witches, a 32-page risograph-printed comic re-interpreting 1950s Harvey Horror comics, plus volume four of our comics section, Early Edition!