FICTION | ISSUE SIX

On the Murder of Nicola Teensmah

♦

By DAVID RICE | Fall 2015

c. 1968

THE MURDER OF NICOLA TEENSMAH, released in a handful of theaters in 1986, is the first and arguably most influential film by Blut Branson, the greatest director ever to come from my town and the man who emblazoned me with the conviction to perhaps someday direct films of my own. Just shy of 30 years later (I should know: the year of its release coincides with that of my birth), it’s finally being canonized by the Criterion Collection, an event I hope will help put my town on the map as the void from which Blut Branson and David Rice emerged.

The film tells the devastatingly simple story of a man whose only calling is to kill a child. This is all that Branson allows us to know about his central figure, whom he terms Dan, a name we only learn from his prison intake file after more than thirty minutes of screentime have elapsed. So, if you will, this central figure begins life as an unnamed everyman and only upon incarceration does he receive the nearly-meaningless moniker he’ll casually bear for the rest of our time with him.

The child he dreams of murdering is named, famously, Nicola Teensmah, after Branson’s first and, according to the one interview he consented to sit for upon the film’s release, “last best friend.”

“I have made the film. I will say nothing more about what happened between us,” his statement concludes, as you may remember, if, unlike me, you were around then, or, like me, have lived in this town in the decades since and seen his interview occasionally replayed on cable access TV between two and four a.m.

IN the film’s opening scenes, we see the-man-not-yet-named-Dan going quietly insane in an unremarkable Southern California apartment, picking things up and putting them down, staring at the clock, grazing from the refrigerator, all while drawing picture after picture with the caption THE MURDER OF NICOLA TEENSMAH. These pictures are powerful, but more disturbed than disturbing, a mess of mutilated child bodies that never achieves aesthetic cohesion.

These early scenes present an absolutely convincing portrait of fantasy wearing itself down, as our man approaches the point at which he will be compelled to do the thing he has for so long nursed in ideation, laboriously shunting his compulsion into the symbolic.

“NO!” the thing inside him is preparing to shout. “No more postponement. The time has come for you to make me real.”

The decisive moment comes when his neighbor, with whom we’ve seen him interact once before, dies and leaves him her modest fortune, which he uses to quit the office job where we’ve seen him sitting at his desk, slowly cutting the flesh behind his knee with a piece of paper. Fully untethered from any normalizing routine, he enters an excruciating funk in his apartment, deep in the darkness of the one room that is not his bedroom.

In a shot that is quintessential Branson, almost to the point of self-parody, a ray of light glints off his left eye in such a way that it remains unclear whether he has generated this light or is reflecting it from some trans-dimensional source. To any viewer who’s seen a Branson film, there can be no question that a grave decision is in the process of being made. When the light stops glinting, he stands up and walks to the courthouse.

In the next shot, he is sitting with the county judge – in Branson’s filmic universe, all business is meted out on the county level – to explain his proposition: “I am willing to spend the majority of my remaining life in prison for the privilege of murdering a child with impunity upon my release.”

“So,” the judge replies, in what I believe has become a catchphrase among Bransonphiles all over the world, “you are in a sense conflating the child’s death with you own, insofar as you are sacrificing your own life at this relatively early stage in order to efficaciously sacrifice another life when yours has already been squandered, thereby renewing yourself through the child, hoping to be reborn as him in the moment of killing.”

“Yes,” says our man. I stifle a sigh of apprehension as I write this, though I admit some of the moment’s power has been lost over the course of successive viewings, often needlessly late at night in the course of preparing this text, when I’ve often wished I were instead preparing an original screenplay of my own.

THE second act opens on Dan in prison (after his name has been revealed on the intake form). We learn that he has been sentenced to forty-seven years, the exact age that Branson was when the film was released, to little acclaim, as is so often the case when the transcendent rears its head into our fallen world of categorization and exchange value.

Dan spends these forty-seven years aging before our eyes, praying to a hand-carved soap statue of the child he will kill upon his release. Forty years into his sentence, with seven to go, he celebrates a quiet birthday alone in his cell, dancing in a circle with the statue in his arms, whispering, “Today you, Nicola Teensmah, are born. When I am released, you will be seven. Today my life begins in earnest as well.”

When I imagine Branson alone in his room, writing these lines, I can’t help but imagine myself inside his body, creating a masterpiece that I will affix my name to in place of his, though I’m aware that this kind of thinking is only a means of delaying the grim duty of finding my own language in my own room upon awakening from the toxic stupor of idol-envy.

WHEN the day of Dan’s release arrives, he walks into the blazing sunshine as a man of seventy-five, played by B. Sanford, father of G. Sanford, who’s played Dan until now, and who also comes from our town, as did his father, may he rest in peace.

The look on B. Sanford’s face was wisely chosen by Criterion as the cover image for their fully-restored two-disc edition: relief to be freed undergirded with terror at the fate his younger self has damned him to. In the film’s only instance of voiceover, we hear Dan think, “Well I figured, since I’d invested my life in it, I’d better follow through, though I sure wished I could’ve taken a pass.”

Over the next ten minutes, we watch Dan wander from one drab location to another – a tire shop, a fast food window, a secondhand clothing market – looking people over, holding their gaze too long, daring them to reciprocate. Anyone who’s seen the film will have an interpretation of this sequence – some claim it should simply have been cut – but I maintain that here Dan warning the people of Greater Los Angeles, through a sort of low-grade telepathy, to keep their seven-year-olds away, in what amounts to his final attempt at Grace.

And it is as if these people have received the message: no children are seen in this sequence, not even in the background, where they have always been before, seemingly oblivious of the camera, or acting out micro-films of their own.

ONCE Dan’s wanderings have taken him as far into the San Fernando Valley as he (and we) can bear to go, he discovers a seven-year-old on the bench of what appears to be a bus stop, though no road passes in front of it.

As viewers of a film, especially a Branson film, we are aware that the boy has been posed like this, but, immersed as we are in Dan’s perspective, stumbling across him feels significantly uncanny. I still cannot watch this sequence without taking a fifteen-minute break before continuing.

After my break, the boy slides off the bench and follows Dan into the dusty afternoon, deepening toward the west. The screen freezes after they’ve disappeared around a bend, until Branson cuts to them in a motel room so sparse it barely reads as a motel room at all: there’s a mattress with no bedding, a linoleum floor with no carpet, a wall with a single window and a curtain blocking out the twilight. I know where this motel is, though had Branson not documented its interior, I wouldn’t have believed it had one, so broken down does it appear nowadays, just past the highway onramp going north toward Sacramento.

As Dan and the boy sit on the mattress, images of a grocery store filter in, like the two of them are processing their memories of shopping in lieu of facing the future. We see Dan picking up packaged cakes and holding them out to the boy, enticingly, almost begging him to accept these treats in a reversal of the typical interaction wherein the son demands what the father insists he cannot have.

The boy simply nods, holding the cakes like the inanimate objects they are, responding with neither relish nor disgust. At the checkout counter, the girl scanning the treats smiles at the boy and says, “Your grandfather must really love you.”

Without meeting her eye, the boy mumbles, “He’s my father, not my grandfather.”

WHEN Branson cuts back to the motel room, Dan is crying. He looks at the boy, turning his back on the camera, demanding a moment of privacy that we are more than inclined to grant.

Then he reaches under the mattress and pulls out a long, curved boning knife. Branson offers no explanation of how it came to be here; he knows that by now we are past the point of expecting realism to spare us what’s coming. Dan waves it through the air, trying to get the boy’s attention. The boy stares downward, seeing the knife when it passes through his line of sight but making no effort to follow it.

We watch as Dan gets increasingly livid. “Look at me!” he finally shouts, revealing how very long it’s been since he has spoken. “You are Nicola Teensmah. I’m sorry, but you are. And for that, you must suffer. If I did not do what I’m about to do, what happened when we were kids would keep happening, on and on through the ages, to both of us in every form we ever took.”

His voice falls to a whisper, as if he’s trying not to hear himself. The knife, stretched between their bellies like a placenta, shimmers.

A howling creeps under the frozen image before we cut to paramedics kicking down the door. Inside, the devastation is so complete it remains indescribable for several seconds.

When we’re finally able to make sense of the room’s interior, all we see is the boy drenched in blood, leaning on the long knife like a cane. There is something old about him, but I’ve never been able to identify what it is. I’ve asked Branson, himself well into old age by now, to which he replies only, “We are all heading in the same direction.”

The paramedics approach warily at first, but Nicola Teensmah is beyond violence. There is no sign of a second body and there is no sound until the boy says, his voice clear and even, “My name is Nicola Teensmah and I’m ready to spend my life in jail.”

Here the screen freezes again, the boy’s face slowly turning into that of the young Dan, which we remember from the film’s opening, indicating the completion of some awful cycle whose nature we will never quite comprehend.

I close my laptop and stand up, thinking, Some day, some day soon, I will begin my life in cinema where Branson’s ended and go that much further into the vast fruitful unknown... I repeat these words desperately, circling my tight living quarters, looking over what I’ve written and fondling the Criterion DVD case until I fall asleep and dream of a version of our town in which thought and action are indivisible.

THE END.

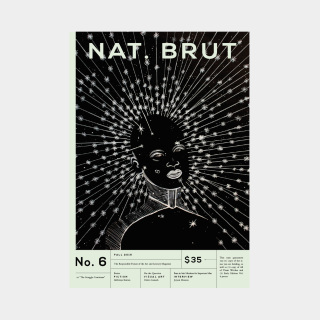

Nat. Brut Issue Six

Issue Six is our second in print, and features work by Cristina de Middel, Afabwaje Kurian, Chitra Ganesh, Jayson Musson, and more! Issue Six also comes with limited edition supplements: All of Them Witches, a 32-page risograph-printed comic re-interpreting 1950s Harvey Horror comics, plus volume four of our comics section, Early Edition!