< Back to Issue Two: Table of Contents

[Essay]

STRANGE FAITH: THE EVOLUTION OF GULLIBILITY

by Andrew Ridker with illustrations by Matt McClure

I. “WOE TO HIM WHO BELIEVES IN NOTHING”

An article by field surgeon Dr. LeGrand G. Capers from an 1874 issue of The American Medical Weekly bears the enthusiastic headline “Attention Gynaecologists!” and reports a bizarre case of artificial insemination. The sequence of events, as recounted by Dr. Capers, are as follows: during the Battle of Raymond in 1863, a Confederate soldier fell to the ground, shot through the left testicle. That very instant, a young woman screamed from inside a nearby house, a lead ball lodged somewhere in her abdomen. A little over nine months later, the woman gave birth to a baby boy. He was a healthy child, save one small thing: the smashed-up bullet in his scrotum. After passing through the soldier, the shot had found its way into the woman, impregnating her. The young virgin had given birth to a literal son of a gun.

Canada, thirty-eight years earlier: more inexplicable documents emerged in the form of the tell-all book Awful Disclosures by former nun Maria Monk. Monk described sexual relations between the nuns and priests of the Hôtel-Dieu convent in Montreal. Pregnancies were dealt with swiftly; protocol dictated that the nun’s babies were to be baptized, strangled, and thrown into the basement. Historian Richard Hofstadter claims that until the publication ofUncle Tom’s Cabin, Awful Disclosures was likely “the most widely read contemporary book in the United States.”

The nation was similarly taken with the story of Sober Sue. A performer in New York City in the early 1900s, Susan Kelly was paid $20 per week to keep a straight face. Willie Hammerstein—vaudevillian, inventor of the pie-in-the-face gag, and father of famed Broadway lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II—issued a proposition to New York’s citizens and comics alike: $100 to whomever could force a smile out of Sue. Though many tried, none succeeded; Kelly maintained her cold, neutral expression all summer long.

[Essay]

STRANGE FAITH: THE EVOLUTION OF GULLIBILITY

by Andrew Ridker with illustrations by Matt McClure

I. “WOE TO HIM WHO BELIEVES IN NOTHING”

An article by field surgeon Dr. LeGrand G. Capers from an 1874 issue of The American Medical Weekly bears the enthusiastic headline “Attention Gynaecologists!” and reports a bizarre case of artificial insemination. The sequence of events, as recounted by Dr. Capers, are as follows: during the Battle of Raymond in 1863, a Confederate soldier fell to the ground, shot through the left testicle. That very instant, a young woman screamed from inside a nearby house, a lead ball lodged somewhere in her abdomen. A little over nine months later, the woman gave birth to a baby boy. He was a healthy child, save one small thing: the smashed-up bullet in his scrotum. After passing through the soldier, the shot had found its way into the woman, impregnating her. The young virgin had given birth to a literal son of a gun.

Canada, thirty-eight years earlier: more inexplicable documents emerged in the form of the tell-all book Awful Disclosures by former nun Maria Monk. Monk described sexual relations between the nuns and priests of the Hôtel-Dieu convent in Montreal. Pregnancies were dealt with swiftly; protocol dictated that the nun’s babies were to be baptized, strangled, and thrown into the basement. Historian Richard Hofstadter claims that until the publication ofUncle Tom’s Cabin, Awful Disclosures was likely “the most widely read contemporary book in the United States.”

The nation was similarly taken with the story of Sober Sue. A performer in New York City in the early 1900s, Susan Kelly was paid $20 per week to keep a straight face. Willie Hammerstein—vaudevillian, inventor of the pie-in-the-face gag, and father of famed Broadway lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II—issued a proposition to New York’s citizens and comics alike: $100 to whomever could force a smile out of Sue. Though many tried, none succeeded; Kelly maintained her cold, neutral expression all summer long.

II. “MAN IS A CREDULOUS ANIMAL”

Behind every hoax is an agenda, an intended outcome. Dr. Capers sought to mock the hyper-embellished battlefield stories told in the wake of the Civil War. Maria Monk’s book, the contents of which were entirely false, was written to fuel anti-Catholic sentiment across North America. Willie Hammerstein turned a woman who couldn’t laugh—most likely due to facial paralysis—into his own personal goldmine.

The receiving end of hoaxes, however, is murkier territory. We understand their reasons for being (to mock, to scam, to entertain), but what is it that makes us believe the unbelievable? It takes little energy to accept the mundane, but no rational person would believe that, for example, a woman could give birth to rabbits—as was purportedly the case with Mary Toft in 18th-century England—without actively deciding that such a thing could be possible.

Behind every hoax is an agenda, an intended outcome. Dr. Capers sought to mock the hyper-embellished battlefield stories told in the wake of the Civil War. Maria Monk’s book, the contents of which were entirely false, was written to fuel anti-Catholic sentiment across North America. Willie Hammerstein turned a woman who couldn’t laugh—most likely due to facial paralysis—into his own personal goldmine.

The receiving end of hoaxes, however, is murkier territory. We understand their reasons for being (to mock, to scam, to entertain), but what is it that makes us believe the unbelievable? It takes little energy to accept the mundane, but no rational person would believe that, for example, a woman could give birth to rabbits—as was purportedly the case with Mary Toft in 18th-century England—without actively deciding that such a thing could be possible.

In a presentation to the 7th Virus Bulletin International Conference, computer security researcher Sarah Gordon proposed five reasons for the spread of hard-to-believe-hoaxes:

I. Trust in authority. (“If a source has proved accurate in many things, it is natural to extend a certain amount of credulity to new information gathered from that source.”)

II. Excitement. (“…we receive a sense of excitement by passing on the hoax, almost like gossip.”)

III. Lack of appropriate scientific skepticism. (“It seems to be the case that we do not even apply the level of skepticism we would when buying a used car to many hoaxes.”)

IV. Sense of importance or belonging. (“The act of sharing [information] helps establish the individual as an integral part of the group.”)

V. Furthering our own goals/self-interest/agenda. (“For the person with a strong belief in "the supernatural" or "the occult", hoaxes about spiritualistic visitations help further their own agenda, bringing strength to their arguments.”)

Gordon’s list provides a helpful, if not simplified, framework for understanding why hoaxes persist. She argues that when it comes to the far-fetched, human beings are some combination of trusting, excitable, and selfish. The greater mystery, however, remains unanswered: why some hoaxes work and others don’t? That is, what in particular would prompt thousands of people to ignore the skepticism and doubt that otherwise governs their lives?

It seems unlikely that hoaxes from the past—Mary Toft’s rabbit births, for instance—would be so widely believed in the twenty-first century. (Toft’s perplexing case convinced, among others, surgeon to the Royal House Nathaniel St André back in the 1720s.) But this is hardly a matter of wising up over time; today’s comparably well-informed public is no less susceptible to modern myths and pranks; it’s hard to ignore the impact of prominent hoaxes like the Bonsai Kitten website from 2000, which advertised house-pet “body modification” and caused such outrage that the FBI was brought in to investigate. And just as Toft’s scheme may not have been so successful today, it’s impossible to determine whether it would have worked in the 16th, 15th, or even 5th century. The best hoaxes—the ones that convince scores of ordinary citizens—depend enormously on place and time, the contextual psychology of its believers. Gullibility never goes out of style; it evolves, just as we do.

III. “CELESTIAL BODIES”

Over the course of one week in 1835, the New York Sun convinced the world that goats, intelligent beavers, and a race of hairy man-bats lived in harmony on the lunar surface.

On Friday, August 21, the Sun ran a tiny page-two notice. It proclaimed: “We have just learnt from an eminent publisher in this city that Sir John Herschel, at the Cape of Good Hope, has made some astronomical discoveries of the most wonderful description.” The articles that followed, written in assured, pseudo-scientific lingo, grew increasingly intriguing and exponentially ludicrous. What follows are highlighted discoveries from the weeklong series:

I. WEDNESDAY: Pelicans, single-horned goats, and an inconceivable “amphibious creature, of a spherical form, which rolled with great velocity across the pebbly beach.”

II. THURSDAY: Abundant “tree-melons” and intelligent, bipedal beavers who live in huts “constructed better and higher than those of many tribes of human savages.”

III. FRIDAY: The remarkable “Vespertilio-Homo”: hirsute humanoids with bat wings and their own spoken language.

IV. SATURDAY: An architectural and spiritual wonder in the form of an “equitriangular temple, built of polished sapphire.”

V. MONDAY: A superior race of Vespertilio-Homo living in close proximity to the temple, “scarcely less lovely than the general representations of angels by the more imaginative schools of painters.”

I. Trust in authority. (“If a source has proved accurate in many things, it is natural to extend a certain amount of credulity to new information gathered from that source.”)

II. Excitement. (“…we receive a sense of excitement by passing on the hoax, almost like gossip.”)

III. Lack of appropriate scientific skepticism. (“It seems to be the case that we do not even apply the level of skepticism we would when buying a used car to many hoaxes.”)

IV. Sense of importance or belonging. (“The act of sharing [information] helps establish the individual as an integral part of the group.”)

V. Furthering our own goals/self-interest/agenda. (“For the person with a strong belief in "the supernatural" or "the occult", hoaxes about spiritualistic visitations help further their own agenda, bringing strength to their arguments.”)

Gordon’s list provides a helpful, if not simplified, framework for understanding why hoaxes persist. She argues that when it comes to the far-fetched, human beings are some combination of trusting, excitable, and selfish. The greater mystery, however, remains unanswered: why some hoaxes work and others don’t? That is, what in particular would prompt thousands of people to ignore the skepticism and doubt that otherwise governs their lives?

It seems unlikely that hoaxes from the past—Mary Toft’s rabbit births, for instance—would be so widely believed in the twenty-first century. (Toft’s perplexing case convinced, among others, surgeon to the Royal House Nathaniel St André back in the 1720s.) But this is hardly a matter of wising up over time; today’s comparably well-informed public is no less susceptible to modern myths and pranks; it’s hard to ignore the impact of prominent hoaxes like the Bonsai Kitten website from 2000, which advertised house-pet “body modification” and caused such outrage that the FBI was brought in to investigate. And just as Toft’s scheme may not have been so successful today, it’s impossible to determine whether it would have worked in the 16th, 15th, or even 5th century. The best hoaxes—the ones that convince scores of ordinary citizens—depend enormously on place and time, the contextual psychology of its believers. Gullibility never goes out of style; it evolves, just as we do.

III. “CELESTIAL BODIES”

Over the course of one week in 1835, the New York Sun convinced the world that goats, intelligent beavers, and a race of hairy man-bats lived in harmony on the lunar surface.

On Friday, August 21, the Sun ran a tiny page-two notice. It proclaimed: “We have just learnt from an eminent publisher in this city that Sir John Herschel, at the Cape of Good Hope, has made some astronomical discoveries of the most wonderful description.” The articles that followed, written in assured, pseudo-scientific lingo, grew increasingly intriguing and exponentially ludicrous. What follows are highlighted discoveries from the weeklong series:

I. WEDNESDAY: Pelicans, single-horned goats, and an inconceivable “amphibious creature, of a spherical form, which rolled with great velocity across the pebbly beach.”

II. THURSDAY: Abundant “tree-melons” and intelligent, bipedal beavers who live in huts “constructed better and higher than those of many tribes of human savages.”

III. FRIDAY: The remarkable “Vespertilio-Homo”: hirsute humanoids with bat wings and their own spoken language.

IV. SATURDAY: An architectural and spiritual wonder in the form of an “equitriangular temple, built of polished sapphire.”

V. MONDAY: A superior race of Vespertilio-Homo living in close proximity to the temple, “scarcely less lovely than the general representations of angels by the more imaginative schools of painters.”

The hoax was an unprecedented success. Edgar Allan Poe, who had tried (and failed) to pull off his own moon-related hoax only two months earlier, remarked that the Sun’s piece “was, upon the whole, decidedly the greatest hit in the way of sensation—of merely popular sensation—ever made by any similar fiction either in America or in Europe.” From what we know of the hoax’s aftermath, Poe’s assessment is spot-on. Other newspapers reprinted the Sun’s articles and circulation shot through the roof. The spectacular news of the lunar inhabitants even reached Europe, translated into multiple languages. But if the hoax hadn’t emerged when it did, it may not have succeeded at all.

The first half of the 19th century saw monumental changes in American life. Two in particular both informed the content of the Great Moon Hoax and ensured its success:

I. Science, particularly astronomy, emerged as a popular interest for the first time, and

II. The Second Great Awakening revitalized Christianity.

Thanks in no small part to the burgeoning newspaper industry—the explosion of penny press newspapers and the invention of the steam press resulted in previously unprecedented rates of circulation—popular science was born in America. Astronomy was of special interest in the early 19th century, prompted in part by the discovery of Ceres, the first asteroid ever observed, in 1801. At the time of the Moon Hoax thirty-four years later, the public was in a unique position. They were fascinated by outer space, but relied almost entirely on newspapers like the Sun for that information. All astronomical discoveries 1830s would have seemed far-fetched, at the very least awe-inspiring—lacking in scientific education but fascinated by the stars, 1835 America would have been particularly prone to newspaper hoaxes of the astrological variety.

So why didn’t Poe’s moon hoax work? In fairness, Poe’s story of a man who flew a hot air balloon to the lunar surface in order to escape his creditors was more outlandish and anecdotal compared to the “scientific” account put forth in the Sun. But the Great Moon Hoax had something else going for it: God.

Americans in the 1830s were a highly religious population. Church membership soared during the Second Great Awakening, which peaked in the 1830s, coinciding perfectly with the emergence of popular science. This watershed moment of religious and scientific epiphanies, however, did not go down easy.

Leon Festinger’s 1956 book When Prophecy Fails examines a cult who believed that the apocalypse would occur on December 21, 1954. Festinger was interested in what happened after the sun rose on December 22, and how the cult would deal with their failed prophecy. The book is best known for coining the phrase cognitive dissonance, which remains one of the most important theories in psychology.

The theory hinges on the discomfort that occurs when a person holds two conflicting beliefs (like the idea that the world will end and the knowledge that it hasn’t, or, say, the belief in the God and heaven of the New Testament and recent discoveries in astronomical science.) “Dissonance reduction” refers to the way people deal with this discomfort, and is traditionally carried out in one of three ways:

I. Changing cognitions, which refers to the simple act of altering one’s beliefs;

II. Altering the importance of the beliefs in question; and

III. Adding consonant beliefs that resolve the conflict.

It was by this third method that Americans wrapped their head around the science-religion problem.

By 1835 there was already a religious movement gaining prominence that hoped to reconcile science and church by introducing a consonant belief: that God had populated outer space with intelligent life. The Natural Theology movement used the complexity of nature as evidence for an intelligent creator, and prominent Natural Theologian Thomas Dick reasoned that because earth is full of “animated existences,” so too should the rest of outer space, the moon included.

Richard Adams Locke, the reporter behind the Moon Hoax, took advantage of Natural Theology’s stance by infusing his astronomical narrative with religious undertones. The hoax’s final installment claims the discovery of a higher-order Vespertilio-Homo, whose ranks were larger, lighter-skinned, and happier than the ones previously described—“in every respect an improved variety of the race.” These superior creatures were said to live in close proximity to the Sapphire Temple and spend much of their time forming triangles with their feet, mimicking its forms. They frolic in what can only be described as a lunar Eden, paying geometric tribute to the mysterious structure; they are, simply put, religious creatures. By populating his imagined moon with pious alien life, Locke was able to reinforce Natural Theology and provide a comfortable solution to the God-science tension that faced his readers—science was valid, insofar as it confirmed religious doctrine. All it took to keep the heavens and planets aligned was to acknowledge that the moon was full of furry, winged zealots. What a relief, indeed.

IV. SPRITES DURING WARTIME

Dear Joe, I hope you are quite well. I wrote a letter before, only I lost it or it got mislaid. Do you play with Elsie and Nora Biddles? I am learning French, Geometry, Cookery and Algebra at school now. Dad came home from France the other week after being there ten months, and we all think the war will be over in a few days. We are going to get our flags to hang upstairs in our bedroom. I am sending two photos, both of me, one of me in a bathing costume in our back yard, Uncle Arthur took that, while the other is me with some fairies up the beck, Elsie took that one. Rosebud is as fat as ever and I have made her some new clothes. How are Teddy and Dolly?

This letter, dated November 9, 1918, was written by eleven-year-old Frances Griffiths from Cottingley, West Yorkshire. Enclosed in the envelope was a photograph of Frances, posing with a wayward gaze while four fairy-women dance in front of her, one of them wingless and playing dual clarinets. To modern eyes—and, really, eyes of any era—the photograph is indisputably fake. The fairies are clearly two-dimensional cutouts, and Frances’s expression reveals a patent unawareness of the magical creatures in front of her. Nevertheless, she insisted on their authenticity. “It is funny,” Frances wrote her friend on the back of the photograph, “I never used to see them in Africa.”

The first half of the 19th century saw monumental changes in American life. Two in particular both informed the content of the Great Moon Hoax and ensured its success:

I. Science, particularly astronomy, emerged as a popular interest for the first time, and

II. The Second Great Awakening revitalized Christianity.

Thanks in no small part to the burgeoning newspaper industry—the explosion of penny press newspapers and the invention of the steam press resulted in previously unprecedented rates of circulation—popular science was born in America. Astronomy was of special interest in the early 19th century, prompted in part by the discovery of Ceres, the first asteroid ever observed, in 1801. At the time of the Moon Hoax thirty-four years later, the public was in a unique position. They were fascinated by outer space, but relied almost entirely on newspapers like the Sun for that information. All astronomical discoveries 1830s would have seemed far-fetched, at the very least awe-inspiring—lacking in scientific education but fascinated by the stars, 1835 America would have been particularly prone to newspaper hoaxes of the astrological variety.

So why didn’t Poe’s moon hoax work? In fairness, Poe’s story of a man who flew a hot air balloon to the lunar surface in order to escape his creditors was more outlandish and anecdotal compared to the “scientific” account put forth in the Sun. But the Great Moon Hoax had something else going for it: God.

Americans in the 1830s were a highly religious population. Church membership soared during the Second Great Awakening, which peaked in the 1830s, coinciding perfectly with the emergence of popular science. This watershed moment of religious and scientific epiphanies, however, did not go down easy.

Leon Festinger’s 1956 book When Prophecy Fails examines a cult who believed that the apocalypse would occur on December 21, 1954. Festinger was interested in what happened after the sun rose on December 22, and how the cult would deal with their failed prophecy. The book is best known for coining the phrase cognitive dissonance, which remains one of the most important theories in psychology.

The theory hinges on the discomfort that occurs when a person holds two conflicting beliefs (like the idea that the world will end and the knowledge that it hasn’t, or, say, the belief in the God and heaven of the New Testament and recent discoveries in astronomical science.) “Dissonance reduction” refers to the way people deal with this discomfort, and is traditionally carried out in one of three ways:

I. Changing cognitions, which refers to the simple act of altering one’s beliefs;

II. Altering the importance of the beliefs in question; and

III. Adding consonant beliefs that resolve the conflict.

It was by this third method that Americans wrapped their head around the science-religion problem.

By 1835 there was already a religious movement gaining prominence that hoped to reconcile science and church by introducing a consonant belief: that God had populated outer space with intelligent life. The Natural Theology movement used the complexity of nature as evidence for an intelligent creator, and prominent Natural Theologian Thomas Dick reasoned that because earth is full of “animated existences,” so too should the rest of outer space, the moon included.

Richard Adams Locke, the reporter behind the Moon Hoax, took advantage of Natural Theology’s stance by infusing his astronomical narrative with religious undertones. The hoax’s final installment claims the discovery of a higher-order Vespertilio-Homo, whose ranks were larger, lighter-skinned, and happier than the ones previously described—“in every respect an improved variety of the race.” These superior creatures were said to live in close proximity to the Sapphire Temple and spend much of their time forming triangles with their feet, mimicking its forms. They frolic in what can only be described as a lunar Eden, paying geometric tribute to the mysterious structure; they are, simply put, religious creatures. By populating his imagined moon with pious alien life, Locke was able to reinforce Natural Theology and provide a comfortable solution to the God-science tension that faced his readers—science was valid, insofar as it confirmed religious doctrine. All it took to keep the heavens and planets aligned was to acknowledge that the moon was full of furry, winged zealots. What a relief, indeed.

IV. SPRITES DURING WARTIME

Dear Joe, I hope you are quite well. I wrote a letter before, only I lost it or it got mislaid. Do you play with Elsie and Nora Biddles? I am learning French, Geometry, Cookery and Algebra at school now. Dad came home from France the other week after being there ten months, and we all think the war will be over in a few days. We are going to get our flags to hang upstairs in our bedroom. I am sending two photos, both of me, one of me in a bathing costume in our back yard, Uncle Arthur took that, while the other is me with some fairies up the beck, Elsie took that one. Rosebud is as fat as ever and I have made her some new clothes. How are Teddy and Dolly?

This letter, dated November 9, 1918, was written by eleven-year-old Frances Griffiths from Cottingley, West Yorkshire. Enclosed in the envelope was a photograph of Frances, posing with a wayward gaze while four fairy-women dance in front of her, one of them wingless and playing dual clarinets. To modern eyes—and, really, eyes of any era—the photograph is indisputably fake. The fairies are clearly two-dimensional cutouts, and Frances’s expression reveals a patent unawareness of the magical creatures in front of her. Nevertheless, she insisted on their authenticity. “It is funny,” Frances wrote her friend on the back of the photograph, “I never used to see them in Africa.”

Frances, age ten at the time, was staying at her aunt’s house in England and spending some quality time with her cousin, Elsie Wright. Elsie copied illustrations from a popular children’s novelty item (Princess Mary’s Gift Book) and fashioned them into cardboard cutouts. The girls then borrowed Elsie’s father’s camera and snapped the photo. Two years later, they went public, and the fairies were soon internationally famous. For sixty-odd years, the Cottingley Fairies were the best evidence for the existence of fairy life on the planet.

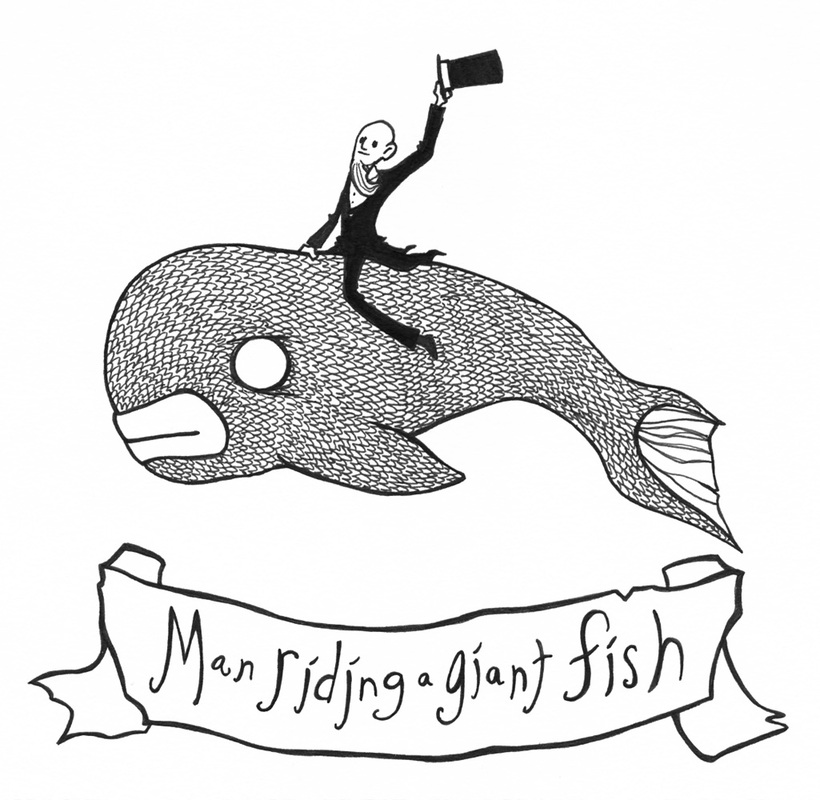

Gullibility in early 20th-century Europe was shaped a great deal by the advent of personal photography; the authenticity of photographs was significantly less disputed in the early 1900s than it is today. Daguerreotypes were phased out in favor of what would become the modern photographic process in the late 1800s, but it wasn’t until the turn of the century that photographs were cheap enough to mass-manufacture and distribute. “Freak photos,” also known as “tall-tale photographs,” which featured manipulated images (like a man riding a giant fish in a lake or a bushel of enormous corncobs) were a popular sensation whose golden era spanned the period before and during World War I. Their popularity was born from novelty; altered photographs went viral because the technology was new, and by extension, the photographs believable. In the pre-photoshop years that conceived of the Cottingley Fairies, this phenomenon was still in its heyday, and had not yet resulted in the cultural distrust of photography that would emerge in its wake.

Gullibility in early 20th-century Europe was shaped a great deal by the advent of personal photography; the authenticity of photographs was significantly less disputed in the early 1900s than it is today. Daguerreotypes were phased out in favor of what would become the modern photographic process in the late 1800s, but it wasn’t until the turn of the century that photographs were cheap enough to mass-manufacture and distribute. “Freak photos,” also known as “tall-tale photographs,” which featured manipulated images (like a man riding a giant fish in a lake or a bushel of enormous corncobs) were a popular sensation whose golden era spanned the period before and during World War I. Their popularity was born from novelty; altered photographs went viral because the technology was new, and by extension, the photographs believable. In the pre-photoshop years that conceived of the Cottingley Fairies, this phenomenon was still in its heyday, and had not yet resulted in the cultural distrust of photography that would emerge in its wake.

As with the Moon Hoax, an existing religious philosophy—in this case, Spiritualism—helped fuel the hoax’s success. Spiritualism, itself a product of the Second Great Awakening, was a belief system predicated on communication with the dead. Gaining prominence around the turn of the century it boasted over eight million followers in the U.S. and Europe by 1897. The photos first gained recognition when Elsie’s mother, who firmly believed in her daughter’s discoveries, took them to a meeting of the Theosophical Society during a lecture on “Fairy Life.” After being verified by Theosophical Society higher-up Edward Gardner and photography expert Harold Snelling, the photos were published in Light, a Spiritualist magazine. Soon after, they fell into the hands of the man whose celebrity would lend credibility to the photos and launch them to international fame.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the writer behind Sherlock Holmes, took a genuine and heartbreaking interest in the paranormal. Depressed after the passing of his wife, son, brother, two brothers-in-law, and two nephews, all who died just before, during, or soon after World War I, Conan Doyle sought comfort in the idea of a life after death. He became a Spiritualist and even joined The Ghost Club, a society that investigated paranormal activity and had counted Charles Dickens and W.B. Yeats among its ranks. Elsie and Frances took four more photos of fairies to show Gardner (who’d been dispatched to visit the girls on Conan Doyle’s behalf) as evidence. Conan Doyle was convinced, and went on to write an article in an issue of The Strand magazine that put the fairies in the spotlight. Despite criticisms (why, for example, did the fairies have “distinctly Parisienne” hairstyles?) and Kodak’s refusal to verify the pictures as legitimate, the photos became immensely popular, and not just among the Spiritualists.

Henry De Vere Stacpoole, author of The Blue Lagoon, famously took the photos at what can only be described as actual face value, writing “Look at Alice’s [Frances’] face. Look at Iris’s [Elsie’s] face. There is an extraordinary thing called TRUTH, which has 10 million faces and forms—it is God’s currency and the cleverest coiner or forger can’t imitate it.” It would be decades before the photos were officially debunked and the cousins confessed, ultimately admitting that they kept the story going because they didn’t want to embarrass the famed creator of Sherlock Holmes. As explained by Elsie in a 1985 interview: “Two village kids and a brilliant man like Conan Doyle—well, we could only keep quiet.”

But beyond Conan Doyle’s endorsement was a somber reasoning behind the hoax’s success. The English public in 1918 did not buy into the hoax merely due to a trust in photography or because some harbored Spiritualist beliefs (which encapsulate two of Gordon’s reasons why all hoaxes persist, Trust in Authority and Furthering Our Own Agenda.) England as a whole, like Conan Doyle himself, was in a state of distress. By the end of World War I, the British army alone had dealt with 80,000 incidents of shell shock (now known as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder), and the public was reeling from the loss of hundreds of thousands of soldiers and civilians. The Cottingley Fairies coincided with the end-of-war and postwar fatigue and depression that plagued Europe, offering life-affirming images in a time of devastation. As if experiencing some kind of reaction-formation—the psychoanalytic phenomenon in which the opposite of an individual’s repressed feelings are outwardly expressed—on a mass scale, the internally-downtrodden British public turned to displaying excessive hope and belief in the fantastical. As Conan Doyle himself put it, “The recognition of [the Fairies’s] existence will jolt the material twentieth century mind out of its heavy ruts in the mud, and will make it admit that there is a glamour and mystery to life.” The Cottingley Fairies took the public’s mind off of the bloodshed that colored the immediate past and left something magical in its place. Frances, in an interview decades later, put it best: “I can’t understand to this day why [people] were taken in! They wanted to be taken in.”

V. MODERN TIMES

During the first week of April, 1996, Taco Bell experienced a sales spike of over a half-million dollars. The fast-food chain, which had yet to introduce the world to Gidget, their iconic Chihuahua mascot, received coverage in over 650 print outlets and 400 broadcast outlets, including NBC’sDNightly News. That same week, interest in a national treasure was revived, leaving the National Park Service in Philadelphia confused and flooded with concerned phone calls. The bizarre events were all tied to a notice placed in six major newspapers from the first of the month:

TACO BELL BUYS THE LIBERTY BELL. IN AN EFFORT TO HELP THE NATIONAL DEBT, TACO BELL IS PLEASED TO ANNOUNCE THAT WE HAVE AGREED TO PURCHASE THE LIBERTY BELL, ONE OF OUR COUNTRY’S MOST HISTORIC TREASURES. IT WILL NOW BE CALLED THE “TACO LIBERTY BELL” AND WILL STILL BE ACCESSIBLE TO THE AMERICAN PUBLIC FOR VIEWING. WHILE SOME MAY FIND THIS CONTROVERSIAL, WE HOPE OUR MOVE WILL PROMPT OTHER CORPORATIONS TO TAKE SIMILAR ACTION TO DO THEIR PART TO REDUCE THE COUNTRY’S DEBT.

Despite the timing of the ad itself (April Fools’ Day) and the fact that the blurb was an advertisement that looked nothing like a true newspaper article, the hoax—cleverly instituted to sell more gorditas, chalupas, and the like—caused a national uproar. According to marketing author Thomas L. Harris, the Taco Liberty bell was a success simply because “in today's world...almost everything is corporate-sponsored.” It was the context of the hoax—historical and psychological—that made the stunt, in the words of activist author Paul Rogat Loeb, “too real for comfort.”

If the success of contemporary hoaxes like the Taco Liberty Bell is any indication, it seems that despite historical trends in improved public education, increased college enrollment, and the instant availability of endless knowledge online, the human race is destined to be fooled forever.

So what do we fall for now? A cursory glance at successful contemporary hoaxes reveals some insight into the present-day public’s particular susceptibilities. There aren’t many moon-creatures or fairies, but in their place are made-up celebrities and conspiratorial computer fonts, a sure sign that far-flung hoaxes are here to stay.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the 21st-century world seems to be most gullible in the very areas that have come to define the postmillennial era. Many major hoaxes of the past twenty-five years—not all, but many—have capitalized upon four distinct modern phenomena:

Consumerism. The Taco Liberty Bell is just one example of the scams and pranks related to corporate and commercial culture that have fooled thousands across the world. A crop circle resembling the BMW logo found in a Johannesburg rye field generated buzz in February of 1993. Eleven years later and a continent apart, more than 3,000 shoppers descended on a much-hyped Czech supermarket before realizing that the building was merely a façade with nothing inside. The ubiquity of corporate culture and advertisements have proven to be fertile ground for successful hoaxes in the late-20th and 21st centuries.

Technology. Bridging the gap between the prominence of corporate culture and the pervasiveness of technology in the information age was the “Microsoft hoax” (the first-ever urban legend email hoax), a fake online article from 1994 claiming that Microsoft had purchased the Catholic Church, aiming to make religion “easier and more fun.” The internet itself has been an incredibly powerful force as both a subject of hoaxes as well as the vessel through which they gain prominence. The line between hoax and reality was infamously blurred with the proposed release of the iLoo in 2003, a port-a-potty complete with a computer and internet access. Microsoft denied the rumors as a hoax, then stated that they were looking into developing the project, then recanted again. It remains unclear to this day whether the project was at any point real or not.

Celebrity culture. The cover for the November 1996 issue of Esquire featured the beautiful, midriff-bearing Allegra Coleman alongside the text “DREAM GIRL.” According to the article, Coleman was the next big thing in Hollywood, appearing in an upcoming Woody Allen film, dating David Schwimmer, and befriending Deepak Chopra. “If Allegra Coleman did not exist,” read the Contributors page, “someone would have to invent her.” And someone did—Coleman was created by Martha Sherrill, the article a work of fiction with a pretty face supplied by model Ali Larter. Similar invented-persona hoaxes include the literary celebrity JT LeRoy (alter-ego of author Laura Albert) and Nat Tate, a fictional abstract expressionist endorsed by Gore Vidal and David Bowie, both of whom were in on the joke. Ever hungry for the next big thing, audiences, the media, and the entertainment industry alike are all too willing to jump on the celebrity bandwagon, even if the star in question does not exist.

9/11. The events of September 11, 2001 changed the way we think about the world, and the numerous hoaxes that followed shed light on how we make sense of the world. There were the unfortunate scams, people seeking money and attention by falsifying deaths of friends and family, and conspiracies, suggesting that Nostradamus predicted the attack or that the Wingdings computer font contained secret 9/11-related messages. And then there were the hoaxes based on hope and recovery, such as the email chain urging Americans to stand outside their homes with lit candles during the night so that NASA could photograph the recovering, illuminated world. The collective light, however, would still not be powerful enough to reach space; no matter how many people believed, America would remain dark. Nevertheless, many citizens reportedly stepped outside their homes with candles lighting their faces, brighter than skepticism, brighter than doubt.

< Previous

Next >

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the writer behind Sherlock Holmes, took a genuine and heartbreaking interest in the paranormal. Depressed after the passing of his wife, son, brother, two brothers-in-law, and two nephews, all who died just before, during, or soon after World War I, Conan Doyle sought comfort in the idea of a life after death. He became a Spiritualist and even joined The Ghost Club, a society that investigated paranormal activity and had counted Charles Dickens and W.B. Yeats among its ranks. Elsie and Frances took four more photos of fairies to show Gardner (who’d been dispatched to visit the girls on Conan Doyle’s behalf) as evidence. Conan Doyle was convinced, and went on to write an article in an issue of The Strand magazine that put the fairies in the spotlight. Despite criticisms (why, for example, did the fairies have “distinctly Parisienne” hairstyles?) and Kodak’s refusal to verify the pictures as legitimate, the photos became immensely popular, and not just among the Spiritualists.

Henry De Vere Stacpoole, author of The Blue Lagoon, famously took the photos at what can only be described as actual face value, writing “Look at Alice’s [Frances’] face. Look at Iris’s [Elsie’s] face. There is an extraordinary thing called TRUTH, which has 10 million faces and forms—it is God’s currency and the cleverest coiner or forger can’t imitate it.” It would be decades before the photos were officially debunked and the cousins confessed, ultimately admitting that they kept the story going because they didn’t want to embarrass the famed creator of Sherlock Holmes. As explained by Elsie in a 1985 interview: “Two village kids and a brilliant man like Conan Doyle—well, we could only keep quiet.”

But beyond Conan Doyle’s endorsement was a somber reasoning behind the hoax’s success. The English public in 1918 did not buy into the hoax merely due to a trust in photography or because some harbored Spiritualist beliefs (which encapsulate two of Gordon’s reasons why all hoaxes persist, Trust in Authority and Furthering Our Own Agenda.) England as a whole, like Conan Doyle himself, was in a state of distress. By the end of World War I, the British army alone had dealt with 80,000 incidents of shell shock (now known as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder), and the public was reeling from the loss of hundreds of thousands of soldiers and civilians. The Cottingley Fairies coincided with the end-of-war and postwar fatigue and depression that plagued Europe, offering life-affirming images in a time of devastation. As if experiencing some kind of reaction-formation—the psychoanalytic phenomenon in which the opposite of an individual’s repressed feelings are outwardly expressed—on a mass scale, the internally-downtrodden British public turned to displaying excessive hope and belief in the fantastical. As Conan Doyle himself put it, “The recognition of [the Fairies’s] existence will jolt the material twentieth century mind out of its heavy ruts in the mud, and will make it admit that there is a glamour and mystery to life.” The Cottingley Fairies took the public’s mind off of the bloodshed that colored the immediate past and left something magical in its place. Frances, in an interview decades later, put it best: “I can’t understand to this day why [people] were taken in! They wanted to be taken in.”

V. MODERN TIMES

During the first week of April, 1996, Taco Bell experienced a sales spike of over a half-million dollars. The fast-food chain, which had yet to introduce the world to Gidget, their iconic Chihuahua mascot, received coverage in over 650 print outlets and 400 broadcast outlets, including NBC’sDNightly News. That same week, interest in a national treasure was revived, leaving the National Park Service in Philadelphia confused and flooded with concerned phone calls. The bizarre events were all tied to a notice placed in six major newspapers from the first of the month:

TACO BELL BUYS THE LIBERTY BELL. IN AN EFFORT TO HELP THE NATIONAL DEBT, TACO BELL IS PLEASED TO ANNOUNCE THAT WE HAVE AGREED TO PURCHASE THE LIBERTY BELL, ONE OF OUR COUNTRY’S MOST HISTORIC TREASURES. IT WILL NOW BE CALLED THE “TACO LIBERTY BELL” AND WILL STILL BE ACCESSIBLE TO THE AMERICAN PUBLIC FOR VIEWING. WHILE SOME MAY FIND THIS CONTROVERSIAL, WE HOPE OUR MOVE WILL PROMPT OTHER CORPORATIONS TO TAKE SIMILAR ACTION TO DO THEIR PART TO REDUCE THE COUNTRY’S DEBT.

Despite the timing of the ad itself (April Fools’ Day) and the fact that the blurb was an advertisement that looked nothing like a true newspaper article, the hoax—cleverly instituted to sell more gorditas, chalupas, and the like—caused a national uproar. According to marketing author Thomas L. Harris, the Taco Liberty bell was a success simply because “in today's world...almost everything is corporate-sponsored.” It was the context of the hoax—historical and psychological—that made the stunt, in the words of activist author Paul Rogat Loeb, “too real for comfort.”

If the success of contemporary hoaxes like the Taco Liberty Bell is any indication, it seems that despite historical trends in improved public education, increased college enrollment, and the instant availability of endless knowledge online, the human race is destined to be fooled forever.

So what do we fall for now? A cursory glance at successful contemporary hoaxes reveals some insight into the present-day public’s particular susceptibilities. There aren’t many moon-creatures or fairies, but in their place are made-up celebrities and conspiratorial computer fonts, a sure sign that far-flung hoaxes are here to stay.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the 21st-century world seems to be most gullible in the very areas that have come to define the postmillennial era. Many major hoaxes of the past twenty-five years—not all, but many—have capitalized upon four distinct modern phenomena:

Consumerism. The Taco Liberty Bell is just one example of the scams and pranks related to corporate and commercial culture that have fooled thousands across the world. A crop circle resembling the BMW logo found in a Johannesburg rye field generated buzz in February of 1993. Eleven years later and a continent apart, more than 3,000 shoppers descended on a much-hyped Czech supermarket before realizing that the building was merely a façade with nothing inside. The ubiquity of corporate culture and advertisements have proven to be fertile ground for successful hoaxes in the late-20th and 21st centuries.

Technology. Bridging the gap between the prominence of corporate culture and the pervasiveness of technology in the information age was the “Microsoft hoax” (the first-ever urban legend email hoax), a fake online article from 1994 claiming that Microsoft had purchased the Catholic Church, aiming to make religion “easier and more fun.” The internet itself has been an incredibly powerful force as both a subject of hoaxes as well as the vessel through which they gain prominence. The line between hoax and reality was infamously blurred with the proposed release of the iLoo in 2003, a port-a-potty complete with a computer and internet access. Microsoft denied the rumors as a hoax, then stated that they were looking into developing the project, then recanted again. It remains unclear to this day whether the project was at any point real or not.

Celebrity culture. The cover for the November 1996 issue of Esquire featured the beautiful, midriff-bearing Allegra Coleman alongside the text “DREAM GIRL.” According to the article, Coleman was the next big thing in Hollywood, appearing in an upcoming Woody Allen film, dating David Schwimmer, and befriending Deepak Chopra. “If Allegra Coleman did not exist,” read the Contributors page, “someone would have to invent her.” And someone did—Coleman was created by Martha Sherrill, the article a work of fiction with a pretty face supplied by model Ali Larter. Similar invented-persona hoaxes include the literary celebrity JT LeRoy (alter-ego of author Laura Albert) and Nat Tate, a fictional abstract expressionist endorsed by Gore Vidal and David Bowie, both of whom were in on the joke. Ever hungry for the next big thing, audiences, the media, and the entertainment industry alike are all too willing to jump on the celebrity bandwagon, even if the star in question does not exist.

9/11. The events of September 11, 2001 changed the way we think about the world, and the numerous hoaxes that followed shed light on how we make sense of the world. There were the unfortunate scams, people seeking money and attention by falsifying deaths of friends and family, and conspiracies, suggesting that Nostradamus predicted the attack or that the Wingdings computer font contained secret 9/11-related messages. And then there were the hoaxes based on hope and recovery, such as the email chain urging Americans to stand outside their homes with lit candles during the night so that NASA could photograph the recovering, illuminated world. The collective light, however, would still not be powerful enough to reach space; no matter how many people believed, America would remain dark. Nevertheless, many citizens reportedly stepped outside their homes with candles lighting their faces, brighter than skepticism, brighter than doubt.

< Previous

Next >