CURATION - ISSUE FOUR

Optic Nerve

CURATED BY KAEL ALFORD & JENNIFER MCNABB

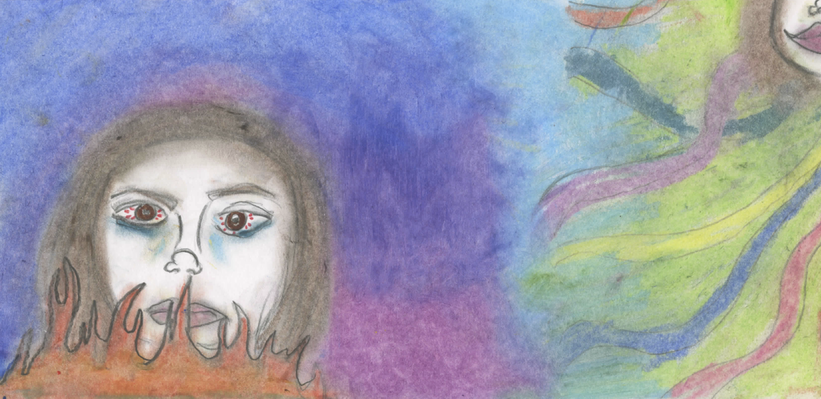

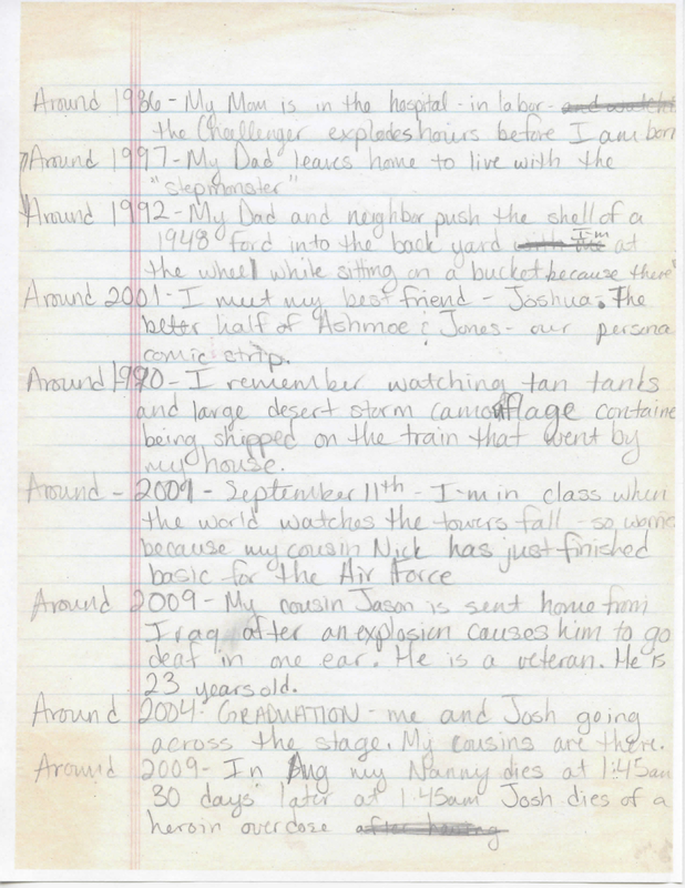

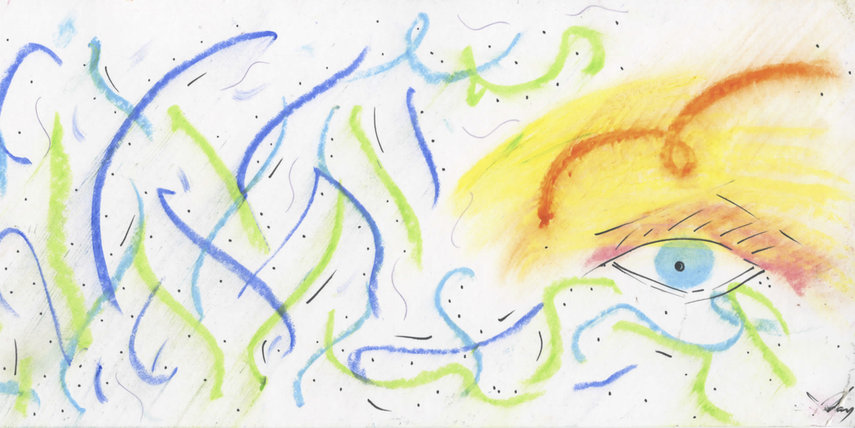

Drawings and texts by women incarcerated in the Dallas County Jail

The work of Resolana, a group that serves incarcerated women in Dallas, drew out the stories of women who were able to identify and express their personal challenges. These stories bore little resemblance to the popular political discourse about crime, drug use, and incarceration, where tougher laws and drug sentencing are so often offered as solutions to what are obviously social and personal crises. This raised the questions, "What if we allowed the experience of these criminals to guide how we fight crime? What if art and personal storytelling from those we incarcerate were used to inform our understanding of crime and our systems of justice?"

-Kael Alford

The number of women incarcerated in the U.S. since 1980 has increased at twice the rate of the male inmate population, fueled mainly by the war on drugs. The vast majority of female inmates in prisons and jails in the U.S. have been victims of physical and/or sexual abuse, both as children and as adults. According to a 2004 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime report, the connection between addiction in women and interpersonal violence is a worldwide phenomenon.

These women’s drug use is linked to trauma. It begins as self-medication, moves to addiction, and often leads to criminal activity. A U.S. Department of Justice report in 2000 points to female criminal activity as mostly “survival crimes,” such as attempts to escape domestic violence situations, support a drug habit, or deal with dire socio-economic circumstances. Most incarcerated women in the U.S. have committed non-violent offenses.

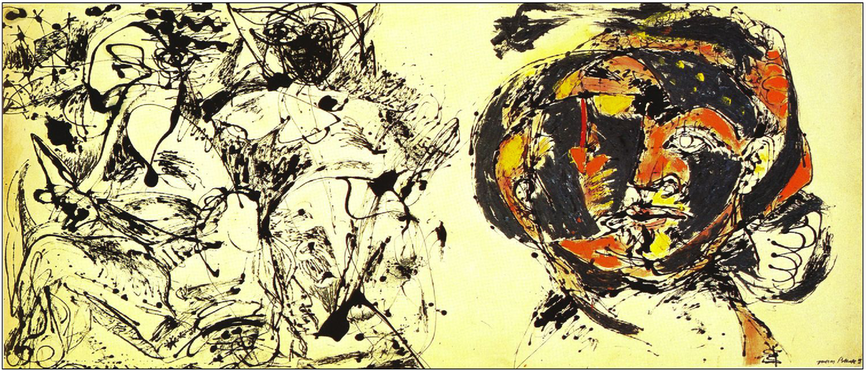

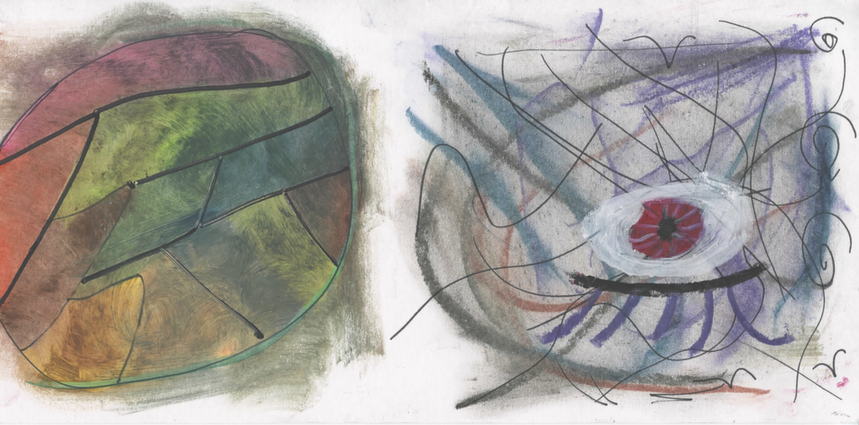

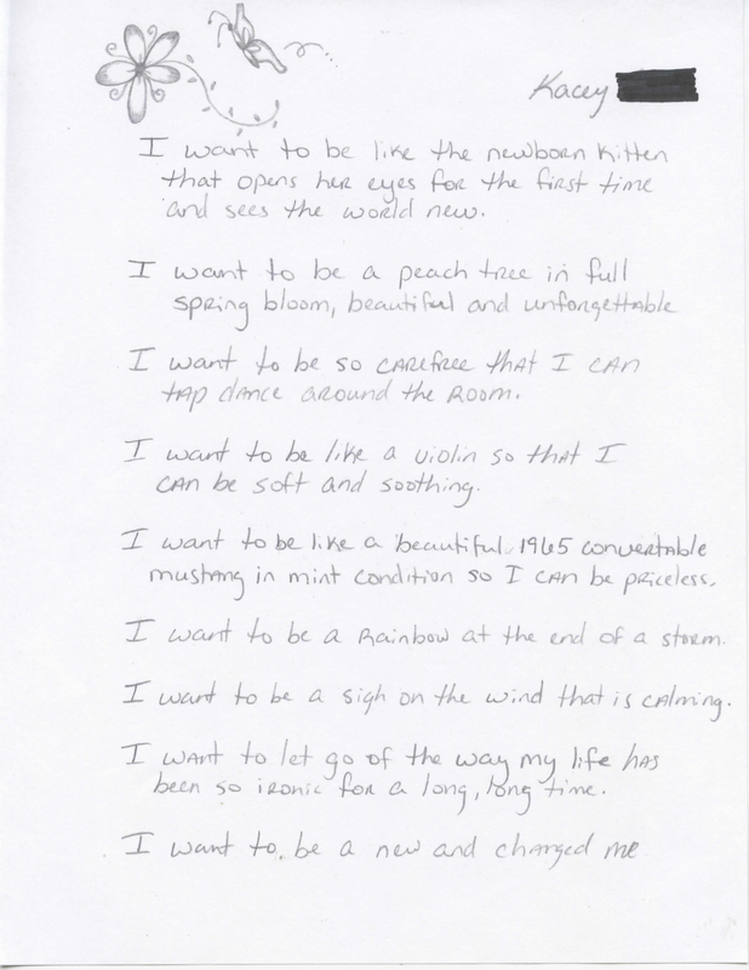

Resolana, now a program of Volunteers of America Texas (VOATX), began as a small agency helping incarcerated women rise above their histories of abuse, addiction, and involvement in the criminal justice system. Resolana’s programming is based on an understanding of how trauma affects the behaviors and attitudes of survivors. Part of Resolana’s holistic approach has been to provide classes that promote self-expression through various art forms: visual art, creative writing, storytelling, and dance. The work in this exhibition is the result of an art class. The class was taught in the Dallas County Jail multiple times over the last four years, and was based on a painting by Jackson Pollack, called Portrait and a Dream, which is part of the Dallas Museum of Art’s permanent collection.

Images stimulate memory, affect, and cognition. Artworks provide a springboard for program participants to create their own artworks. Spending time behind bars can permanently marginalize people; taking the art museum into the jail is a step toward including them in the larger community.

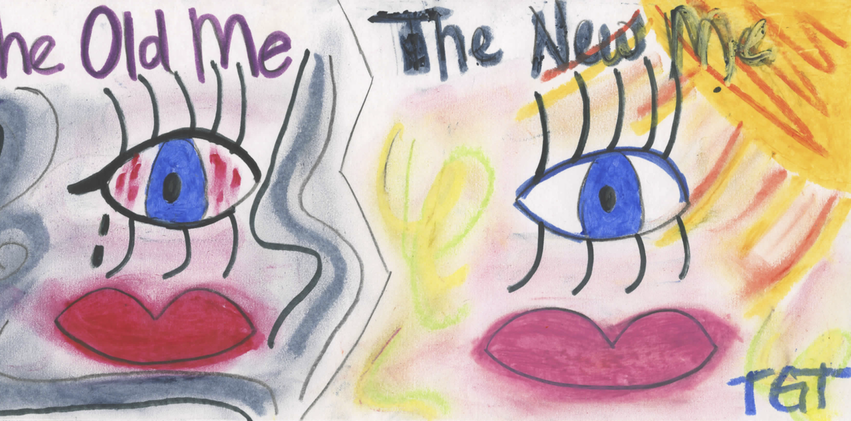

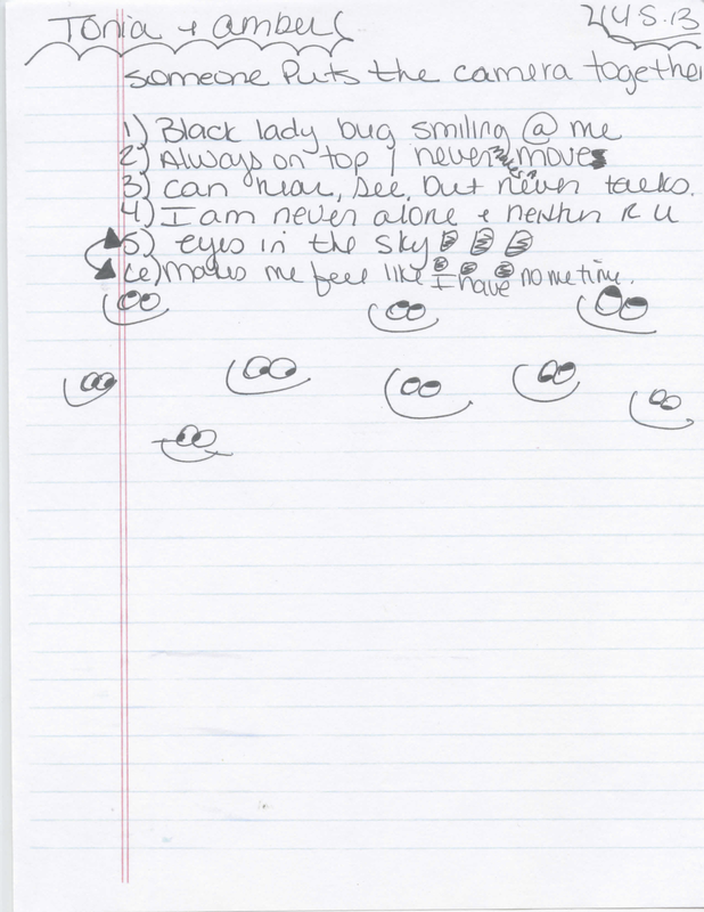

In class, the women respond spontaneously to the artwork. The only instruction I give is to make a piece of visual art with two parts based on the women’s own narratives. Their pieces most often depict their lives in addiction and their lives in recovery. Only after reviewing the products of classes over several years did I notice another, more covert, recurring motif: the ever-watchful eye.

Hyper-vigilance and hyper-arousal are trauma symptoms. The trauma survivor anticipates - expects even - to re-experience the trauma of her past. Continued survival depends upon remaining vigilant. Only one woman in four years has explicitly alluded to the eye as symbolic of her watchfulness, but the image recurs and appears emblematic of an ever-present anxiety.

In these works, the eye appears to symbolize the self. This habit of surveillance is mirrored by the criminal justice system. Cameras and correctional staff watch while they are in jail, and in “the free” they are supervised through drug tests, ankle bracelets, and probation and parole officers. The line between the watchers and the watched becomes blurred, and anxiety becomes normalized.

-Jennifer McNabb

Kael Alford is a journalist, photographer, writer and educator who is based in Dallas, Texas where she teaches part-time at Southern Methodist University. She develops long-term documentary based projects that challenge dominant social and cultural narratives.

Jennifer is an art educator and creative writing instructor who has been working with inmates in Dallas County Jail for the past 6 years. She has designed curricula for the creativity component of Resolana’s psychoeducational program for women inmates, and most recently worked with a colleague to design and implement a mentoring program to train volunteers to mentor inmates.

Jennifer is an art educator and creative writing instructor who has been working with inmates in Dallas County Jail for the past 6 years. She has designed curricula for the creativity component of Resolana’s psychoeducational program for women inmates, and most recently worked with a colleague to design and implement a mentoring program to train volunteers to mentor inmates.

NEXTPOETRY

|

RELATEDCURATION

|

INTERVIEW

|

VISUAL ART

|