VISUAL ART

Art and Protest:

Piece It Together

♦

Work by SHANNA MEROLA and SHEIDA SOLEIMANI

with an essay by BERYL SATTER | 5 September 2016

with an essay by BERYL SATTER | 5 September 2016

Shanna Merola, "We All Live Downwind Untitled," Archival Inkjet Print, 2014

This essay was written in tandem with the show Piece It Together, featuring work by Shanna Merola and Sheida Soleimani,

at the University of Toledo Center for Visual Arts Gallery in winter of 2015.

at the University of Toledo Center for Visual Arts Gallery in winter of 2015.

What does it mean to be faceless?

Facelessness renders the powerless invisible. It’s also used by the powerless to assert their agency. Women cover their faces with cosmetics to hide age or emotion. Anarchists cover their faces when they vandalize the powerful; so do killers of all ideologies. What does the executioner’s hood mean in this context? The burqa that marks an adult as female while masking her individuality? The blindfolds placed over the eyes of the executed? When are faces absent because of the viewer’s inability to see? Because of vision blinded by privilege? Or tears? Or blood? Or tear gas?

|

A muted chanting emanates from a small screen containing footage of protests in Ferguson during the Summer of 2014. Drumming and dancing is accompanied by a call and response often led by women or girls. The mood is joyous and defiant, but the words are serious. “Please don’t shoot me dead, I’ve got my hands on my head.” “The whole damn system is guilty as hell.” “We want freedom.”

Enter the gallery. On one side is Shanna Merola’s installation, “We All Live Downwind.” Her focus is the “aftermath of supply and demand,” and more specifically, the poisons left behind in dying industrial landscapes once fueled by oil “bubbling from the earth below.” On the other is the work of Iranian-American Sheida Soleimani. Her father was a pro-democracy activist who fought the theocratic regime that seized power in the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Her mother was tortured by Iranian officials as a result of her father’s activism. Soleimani has been formed by her parents’ struggles, yet inevitably views them from a historical and cultural remove. She explores responses to Iran’s political upheaval by both “East and West”—and in her own divided psyche.

"Facelessness renders |

Shanna Merola, video installation, Ferguson, MO, 2014

|

The artists are separated by space and delineated by color palette—Merola’s collages embrace a spectrum of blues, while pinks and reds mark Soleimani’s works. Bridging the two sides of the room is the command “Piece it Together.” We are asked to bridge male and female, “East” and “West,” oil producer and oil consumer, colonizer and colonized. But how can you piece it together when each collage is a spectrum in itself—spectrums including the powerless and the powerful, the voiceless and the loud, the contaminated and the pure?

Piece It Together, Center for Visual Arts Gallery at University of Toledo, 2015

|

We are asked to view each of Merola’s collages differently, as their frames, like mutated appendages, become different typologies for disaster. They are untitled and become specimens inside the specificity of the frames. One collage shows a brown linoleum floor, warm and familiar like one’s childhood basement. Yet there’s been an implosion; the floor is covered by thick shards of glass and yellow chips of paint. Staring out from the center of the wreckage is a human eyeball. Its iris is forest green, its pupil a disturbing and unnatural sky blue. Without a face, lacking race or gender, the eye is stripped of markings of power. On one hand it looks achingly delicate, the blue pupil chemically spoiled, the eye vulnerable to cuts from the shattered glass nearby. On the other, it’s possibly the eye of a voyeur, peering in to either enjoy the spectacle of the wreckage or keep it under surveillance.

|

Shanna Merola, "We All Live Downwind Untitled," Archival Inkjet Print, 2015

"Without a face, lacking race or gender, the eye is stripped of markings of power." |

Merola’s collages concern a particular duality that is reflected in the curatorial direction of the show—between oil, the fuel of industry, fire, and war, and water, the requirement for life. Another collage features two men; one black, one white. They appear to be working together, reaching towards large plastic-wrapped containers of bottled water, possibly to distribute to the victims of a disaster. Yet their gestures appear as though they are throwing grenades, or tear gas. The men are headless. Are we meant to see them as “mere workers” of a disaster-capitalist society—all body, no mind? Behind them, in the distance, are lines of police. There’s smoke, familiar from the annals of recent and historical news coverage of racial conflict. It could be 1967 in Detroit. It could be 2014 in Ferguson. Are the two men distributing water for different sides of this confrontation? The smoke appears to be rolling towards them. They are untouched for now. They won’t be for long. What can small, individually packaged bottles of water do against this fire?

Shanna Merola, "We All Live Downwind Untitled," Archival Inkjet Print, 2015

Merola’s image of rescuers distributing water in front of smoky clouds brings me back to Manhattan in the days after 9/11. I remember the poles and street signs covered with hand-made posters by people searching for spouses, siblings, children, roommates, or friends last seen at the World Trade Center; the sirens streaming down the West Side Highway to the Trade Center site; and that everywhere one looked there were stacks of bottled water. They were a sign of caring that became, for me, a sign of chaos and helplessness. I saw a line of people, winding for blocks, waiting to register the names of missing loved ones. Each person in that line represented one of the approximately 3000 killed that day. Every twenty feet or so, volunteers offered the people bottled water. What could water do in this context? I passed railings covered in soft white Trade Center ash. Someone had scrawled the words “Kill all Arabs” in it. I erased the hateful message with my hand. Then I realized what I was touching: ash made of melted steel and glass, burnt paper, clothing, carpets, furniture, industrial engines, and dead bodies. I could wipe the message of murder off the railing, but could I get the chemical stew of modern death off of my hand?

|

Shanna Merola, "We All Live Downwind Untitled," Archival Inkjet Print, 2015

"we see a cycle of connection and pain" |

A small collage shows three plastic gallons of water. On each, spray-painted in blue, is “W/O.” With out. Jugs full of water that say they are without water. Merola’s water bottles are alive. Protruding from one of the plastic jugs is the arm of a man wearing African clothing. The arms pour orange-brown water into a blue plastic basin held by two arms that belong to an African woman. The brown water bubbles in her basin. We see that there are gradations to being “without.” Without running water. Without potable water of any sort. With little but your arms.

In another collage, against a backdrop of a decaying room, three people in formless sky-blue suits—the kind worn to perform a surgical operation, or to clean up after a disaster—form a circle around a pit. They have heads, but their faces have been carefully excised. They pour thick black oil into the pit. They wear gloves to their elbows. The gloves glisten, slick and oily, like the appendages of amphibians. |

They are elbow-deep in a red substance that evokes blood, yet they are entirely protected from its consequences. But they are not isolated in their work; instead, they form the top arc of a circle. The bottom arc is an oversized, exposed human hand, white, palm up. It has gruesome stitches in the center of its palm and a malformed thumb that looks more like a flipper. The hand's fingers graze a baby seal whose fur still white, its flippers extended, and its eyes looking out from a bashed, red and purple face. We see a cycle of connection and pain.

Shanna Merola, "We All Live Downwind Untitled," Archival Inkjet Print, 2014

|

“Hands up, don’t shoot—Black lives matter.” The sound of the video that we had to strain to hear upon entrance seems to be bellowing through the gallery space as one approaches the collage that features the square photographs of hands. Most are pudgy baby hands. They are white, brown, and black. There is one problem: they all have an extra finger. Sometimes it’s an extra thumb growing out of their “normal” thumb. Sometimes it’s an extra pinkie, or two index fingers instead of one. The photos of hands are impaled on sticks, which could, in their most optimistic reading, be protest signs. The seal, the faceless men, and the arms protruding from the water jugs are the harbingers of what happens when life is not valued, or when we disregard humanity. Invisible. Without a face.

|

Shanna Merola, "We All Live Downwind Untitled," Archival Inkjet Print, 2014

|

|

Shanna Merola, "We All Live Downwind Untitled," Archival Inkjet Print, 2015

|

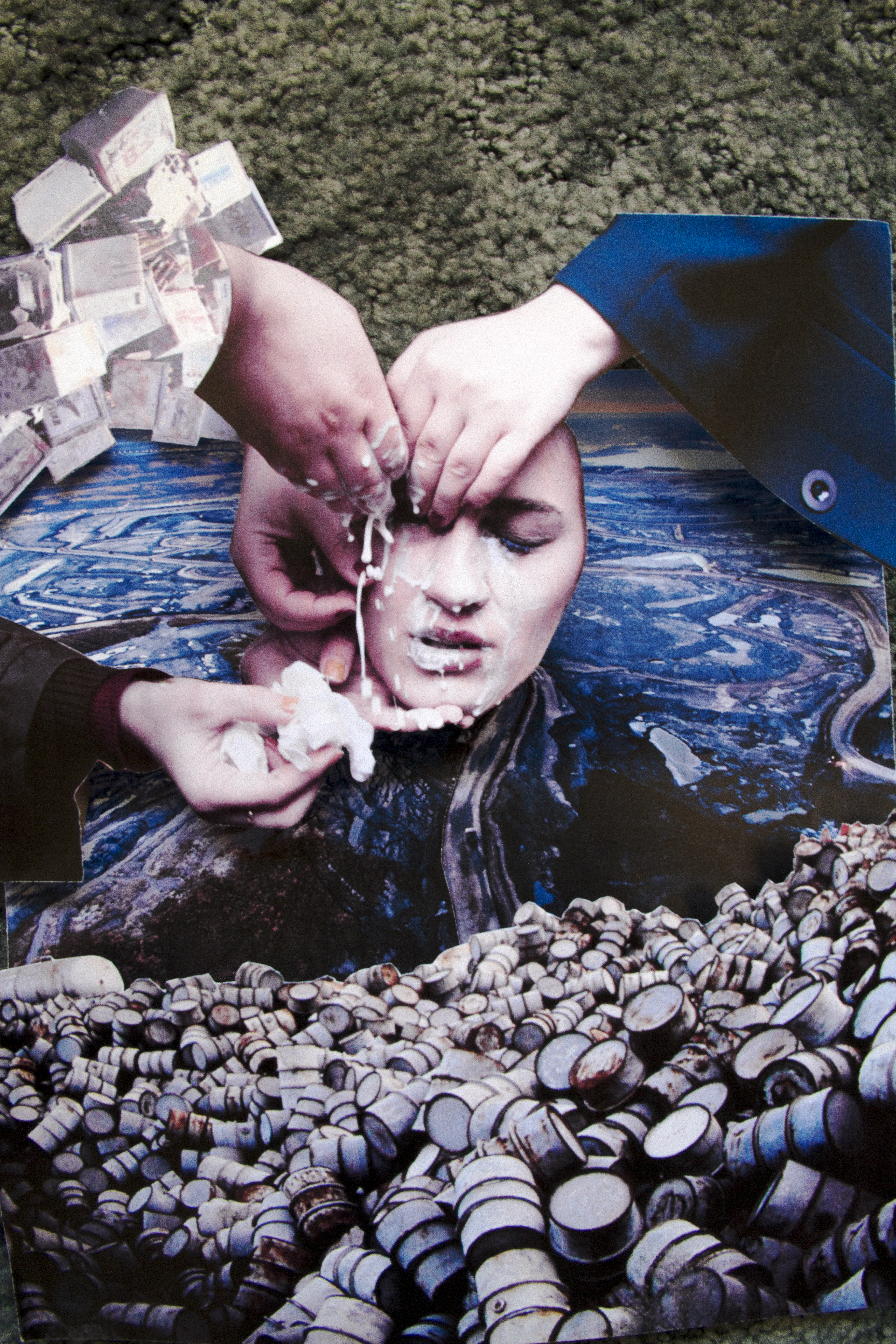

Merola’s installation contains only one collage showing a fully revealed human face. It appears female, though it might not be. It could be Middle Eastern, though maybe not. Five disembodied white hands surround hir face. Two appear to be prying open one of hir eyes. Is s/he being forced to see? Or is hir eye opened only to be cut and blinded? A third hand, sporting nail polish, is wiping white liquid off of hir face. Is it cum? Or is it milk, used to clear tear gas from one’s eyes? The process of restoring vision is shocking, and it hurts. Behind hir is a ethereal swirl of blue and white. It could be the planet earth from a distance. Zoom in closer; it’s an aerial view of a landscape—the ribbons of blue are superhighways viewed from on high. Then back up and it’s something else: an oil spill. Are they all the same thing? It’s a matter of perspective.

"each collage is a spectrum...including the powerless |

***

Merola’s work evokes the crumbling rustbelt cities and victims of environmental disaster of postindustrial U.S.A. Sheida Soleimani’s starting point is approximately the same time period, but the other side of the world. Soleimani mixes pixelated social media images leaked out of Iran during the recent past with smooth, detailed photographic still-life images made in the United States. While Merola’s collages are presented in disorienting typologies-turned-frames, Soleimani’s collages are equalized by their standard framing, yet they, too, remain untitled in this space.

Piece It Together, Center for Visual Arts Gallery at University of Toledo, 2015

In one collage, the tanned shanks of a hooved animal—perhaps a lamb—appear life-size, while everything surrounding the shanks is miniaturized. The shanks look delicate and feminine, in part because their hooves have been painted with nail polish. One hoof is a glossy orange; the other is painted an even shinier pink, the still-wet nail polish brush lying just to its side.

|

Nail polish is a sign of cultivated femininity, of course. But it can’t be fully separated from the world of extraction, power, and exploitation. Nail polish makes a hard substance harder. It covers and exaggerates. The polish itself is made out of chemical compounds including oil, plastic, and ethanol. There have been reports of the women who work in nail salons getting sick and even miscarrying after breathing in nail polish fumes throughout their ten or twelve-hour workdays. In the U.S., salon workers are often immigrants from lands where there have been U.S. military or economic interventions, which too often concern access to oil. The very materials used in the cultivation of femininity hint at the multiple layers through which women’s lives are disrupted by international power relations over which they have no input and little control.

The lamb legs in Soleimani’s piece emerge out of a Lego castle that’s been coated in glossy orange nail polish. Against a bright orange background made of shiny paper, paint, and party ribbons, we see two shirtless men with their backs to us, heads bowed and hands raised over their heads. The image of the two men is duplicated at least four times, forming a half-circle around the lamb shanks. Each image becomes increasingly pixilated and abstract via repetition. Only one, in the bottom right corner, is clear enough for us to see that the men have blood running down their backs. The pixilation reduces the men’s bodies to dehumanized squares, echoing the childish square tops of the orange Lego castle. Has the orange nail polish been poured over the castle-top to hide what state power is really made of? Vulnerable human beings? Delicate sacrificial lambs?

|

Sheida Soleimani, "Tanned," 24"x17", archival pigment print, 2014

"the sacrificed |

Peeking out from behind the lacquered castle is a pile of bodies, face-down. The pile is flat, made of duplicate images of the same two men. As in Merola’s work, the sacrificed (and the sacrificers) remain faceless, flattened, and barely discernible behind the glossy surface of state power. “Please don’t shoot me dead, I’ve got my hands on my head,” the Ferguson protestors chant. Pleas—whether they are incomplete trickles of information that emerge from Iranian social media or the repeated chants of Ferguson protestors, glossed over by the overzealous news coverage that stylizes and simplifies protest—go unheeded.

|

Sheida Soleimani, "Halal," 24"x17", archival pigment print, 2014

|

At first glance, Soleimani’s next collage sits in stark contrast to the design attributes of dripping orange and pink nail polish. The background is shiny white wrapping paper with black speckles. In the foreground is a toy bulldozer or crane painted white. Talon-like hands crawl across the bulldozer and up the neck of the crane. There’s a silhouette shaped like a bird’s head at the top of the crane, which forces us to shift perspective and see the entire crane as a giant white bird. The bird has a ruff of black feathers along the back of its head; closer inspection reveals the ruff to be made out of false eyelashes.

The only color in the image emanates from several tiny orange cranes nestled in the wrapping paper. A horrifying realization: men’s bodies hang from the cranes, their hands tied behind their back. Men in black—some holding clubs, their backs turned to us—oversee this “construction” site. The faces of both killers and victims are hidden. In the lower left corner is a pile of scaly bird talons, echoing the pile of bodies in the previous image. "Everything is inside out. Machines |

The black speckles on the white paper give the appearance of landscape that is snowing oil. Everything is inside out. Machines build death. It rains oil, not water. And looming over the entire scenario, on a scale larger than any other in the image, are the shadows of two human hands. One is dark, a mere shadow; the other is white with dark speckles. They turn towards each other, but don’t yet touch. Are they raised in surrender? Or in protest?

Piece It Together, Center for Visual Arts Gallery at University of Toledo, 2015

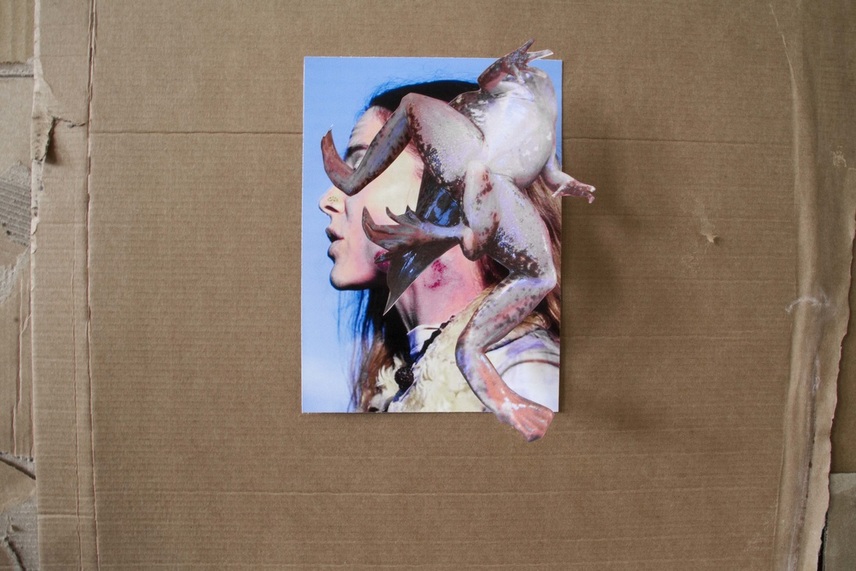

Soleimani’s second wall turns to the domestic world of food, grooming, beauty, and sexuality. Yet this arena, too, is suffused with violence. In the background of the first collage on this wall are two iterations of a woman’s face, with yellow hair and painted lips, pursed and shiny. In the foreground, a fish, still raw but prepared for consumption, curls backwards. Its belly is filled with red pomegranate seeds, like roe. Its gills are stuffed with rice and a few more seeds of pomegranate, and its glassy round eye is enhanced with purple eyeliner and false eyelashes. Scattered throughout are more pomegranate skins and seeds, clumps of rice, pink razors, and small curls of black hair. They hint at a violent messiness behind the preparation of both a manicured meal and a “feminine” appearance, blond and hairless.

|

The pink-lipped woman has a face, but no eyes. The first iteration of her image, in the background, features a bruised, whitish-pink eyeball barely visible through a mostly shut left eye. The right eye is missing altogether. Oil drips down from the top of the collage, one strand of it covering her yellow hair with black. Compared to Merola’s work, the politics of oil are more personal here, and more immediate. The woman may have been beaten. The oil in her makeup, and the oil that purchases her domestic place, is on the surface, destroying the manicured appearance.

The second iteration of the woman’s face is larger. A pink razor punctures the spot where her left eye should be. In place of the right eye, a cloth eyelid has been sewn; it has eyelashes and serves as a pocket to hold a second pink razor. We see pinkish circles on her pixilated yellow hair. They could be tiny sex organs or scars from cigarette burns. Curls of black hair, or perhaps smoke, spiral out of the pinkish circles. They are located on her brain, suggesting the intensity of indoctrination. A few pomegranate seeds are scattered across her upper lip and chin. Pomegranates originate in and are often grown in Iran; we see how women are marked by the history of the nation. The seeds resemble drops of oozing blood, perhaps the result of cuts from the razors as she prepares herself to be seen, but not to see.

|

Sheida Soleimani, "Filleting," 24"x17", archival pigment print, 2015

|

Only the eye of the fish is wide open. The fish appears to be impaled over a triangle of pinkish flesh. Sticky black oil drips from the fish’s back. The fish is both a meal and a woman. Its exposed belly full of seeds reveals the sexuality and reproduction she can’t control. Her suffocation and silence is depicted by the rice crammed not into her mouth, where it might feed her, but her gills, where it suffocates her.

|

Sheida Soleimani, "Geography of the Refugees," 24"x17", archival pigment print, 2015

"this arena, too, |

At the center of the next tableau are two crossed swords. Both are pink, set against a translucent, pinkish backdrop. The larger one appears to be an inflated plastic toy. Two partially burned cigarettes spout from the top of the inflated sword like the antennae of an eyeless slug. The blade of the smaller sword is flat; it could be made of cardboard. Its tip has a fringe made of false eyelashes, giving it the appearance of a closed eye. It leans delicately against the side of the larger, inflated sword, held there by a single string. It could be an umbilical cord. The relationship between of the large sword and the smaller one seems maternal and protective, but it is the blind leading the blind. The burnt ends of the cigarette antennas on the inflated sword hint at an extremely delicate balance: they could puncture the inflated sword or incinerate the cardboard, but as of now, they are the only mechanism with which to see. A partially foil-covered hand is uncovered enough to reveal a wedding ring. It emerges from a white base and is stationed protectively in front of the flat sword. Another hand, most of its foil peeled off, emerges from a black base and guards the inflated sword. Again, the two hands reach out to each other, but are far from touching. Womanhood and intergenerational female relationships are burned, smothered, or mummified in the very process of cultivation—this collage’s foreground features bunches of green grapes, intermixed with grapes that have been spray-painted white. Disturbingly, some of the grapes have false eyelashes on them, making them resemble disembodied eyeballs, unseeing and unaware of their fate.

|

The next image again features a bird, in this case a large hooded falcon. It continues Soleimani’s exploration of the constrictions of femininity within the Iranian dictatorships. The falcon dominating the image is an aristocratic bird of prey, known for sharp eyesight and the ability to hunt; it seems to connote terror surveillance. Yet its hood is made of a glossy pink substance of plastic or latex. The color associates the bird with femininity, while the texture links it to plastic bags that can suffocate both people and the environment. The falcon stares down at its own talons, implying self-surveillance.

|

The falcon’s wing is impaled on a triangle made of pixilated purples the color of bruises. This creates a sense of the bird’s confinement and pain. The purples are extremely enlarged images of pomegranate seeds. Ripped open pomegranates are strewn across the bottom of the image as well. Both the enlarged purples and the open pomegranates look disturbingly like the interiors of torn bodies. The collage includes two iterations of a purple, almond-shaped object. One resembles swollen lips, wounded and sexual. The second iteration is identical except that false eyelashes have been appended to one side. This makes the swollen lips look instead like bruised eyes swollen shut. Only the captured or the dead have eyes to witness the atrocities of power.

A final image, on a wall all to itself, finally shows faces with eyes open. Like Merola’s sole collage containing a fully revealed face, Soleimani’s final image addresses gender and power. It contains six faces, all replications of a single image. All wear a black mask that reveals only eyes, lips, and a bit of a mustache. The eyes stare upwards, as if fastened upon a star.

Sheida Soleimani, "Judge, Jury, Executioner," 24"x17", archival pigment print, 2015

|

Sheida Soleimani, "Trainer," 24"x17", archival pigment print, 2015

"Only the captured or the dead have eyes to witness The first impression is of women wearing beautifying face masks, perhaps of mud. In the upper left corner, however, is one image that transforms the meaning of the other five. Here alone, an arm accompanies the masked face. It is the arm of a man, raised in a threatening manner, as if about to strike. It’s now clear that the face mask is actually that of a killer or an executioner. The raised eyes are focused not on a star, but on a target. Instead of women striving to become more feminine, we see that a man with beautiful eyes can also be a killer. Gender may be malleable and cultivated, but the arm of power minimizes its power to disrupt authority. |

Hands up—don’t shoot. It’s time to piece it together. Oil was the source of British and U.S. insistence on control over Iran’s destiny, the cause of U.S. support for autocratic secular rulers that triggered, in turn, the extreme theocracy of the Iranian Revolution. What does it mean to take control over the life of another, or to hijack the subsistence of a landscape far removed from one’s own? Are the hands of a thousand, thrown up in protest, more potent than the arms of a drone operator? The collages of Soleimani and Merola present us with variations of accommodation and resistance. We observe the ecological violence of unequal access to—and misuse of—oil and water, and the bloody politics that such inequality spawns. We see problems of perspective, and the relativity of suffering. Facelessness foments biological mutation and abuse of biological life. Facelessness means that Iranians are encompassed within the “kill all Arabs” message pressed into the white ash of the World Trace Center—never mind Iranians’ identity as non-Arab, never mind their inclusion of men and women who suffered and died for a democratic Iran, as well as masses who obey their leaders out of fear or, as Americans do, because of ignorance and passivity. Facelessness means we see no distinctions.

Warped or partial vision enables tragedies, from post-industrial economic devastation and ecological mutation to state-sanctioned executions and indifference or glee over the suffering of the “other.” Surveillance can be used to enforce exploitation, but clasping hands and witnessing with open eyes offers a way out. The energy and exuberance of the Ferguson protestors seems all the more crucial in this context. The chants we hear in the background—“Black lives matter,” “hands up, don’t shoot,” “the system is rotten,” and “freedom”—remind us that battles for human dignity are international, and they are happening now.

Shanna Merola, video installation, Ferguson, MO, 2014

The work above appeared in the show Piece it Together, October 11 - December 6, 2015 at University of Toledo,

Department of Art, Center for the Visual Arts Gallery. Curated by Brian Carpenter, Gallery Director and Lecturer of Art.

Images courtesy of the artists & Brian Carpenter.

Department of Art, Center for the Visual Arts Gallery. Curated by Brian Carpenter, Gallery Director and Lecturer of Art.

Images courtesy of the artists & Brian Carpenter.

|

Beryl Satter is Professor of History at Rutgers University-Newark. Her book Family Properties: Race, Real Estate, and the Exploitation of Black Urban America (2009) won the Organization of American Historians’ Liberty Legacy Award for best book in civil rights history and the Jewish Book Council’s National Jewish Book Award in History. It was a finalist for the J. Anthony Lukas Book Prize, and for the Ron Ridenhouer Book Prize, awarded to “those that persevere in acts of truth-telling.” She is a cofounder, with Darnell Moore and Christina Strasburger, of the Queer Newark Oral History Project (http://queer.newark.rutgers.edu). To support her current book project, a history of a pioneering community development bank called ShoreBank, she won a Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship in 2015, and was selected as an Andrew Carnegie Fellow in 2016.

|

|

Sheida Soleimani is an Iranian-American artist, currently residing in Providence, Rhode Island. The daughter of political refugees that were persecuted by the Iranian government in the early 1980s, Soleimani inserts her own critical perspectives on historical and contemporary socio-political occurrences in Iran and the greater Middle East. Her works meld sculpture, collage and photography to create collisions in reference to Iranian politics throughout the past century, as well as dissecting how both the East and West respond to international climates. By focusing on media trends and the dissemination of societal occurrences through the news, source images from popular press, and social media leaks are adapted to exist within alternate scenarios.

|

|

Shanna Merola is a lens-based media artist who lives and works in Detroit, MI. Her artwork is informed by the current and historic political landscape of the city. In addition to her studio practice she is a documentary photographer for grassroots social justice organizations. Working for civil rights attorneys she documents at protests and facilitates workshops on best practices during police encounters. Her collages and constructed landscapes are informed by the rallies she documents - from direct actions against fracking companies to the privatization of water both globally and locally. She is currently working on a collaborative production of Know Your Rights Theatre, inspired by the politically radical puppet troupes of the 1960’s.

|